Argentina Is Anxious for Soy Dollars. Farmers Won’t Play Ball

Argentina’s Anxious for Soy Dollars. Farmers Aren’t Playing Ball

(Bloomberg) -- Aimar Dimo beamed as he showed off a cellphone video of a combine harvester reaping a bumper corn crop on his farm set amid Argentina’s storied Pampas. The country’s central bank, fighting to defend the world’s worst-performing major currency, will be equally happy -- as long as the crop is sold quickly and the dollars brought into the country.

And there’s the rub. Dimo and his fellow farmers have no such intention.

Thanks to the shaky currency, and a trade war that’s depressed global markets, the growers are likely to store much of the harvest. They’re betting on higher prices later in the year and a weaker peso -- exactly what the central bank is trying to avoid. Policy makers have pushed interest rates above a world-beating 60 percent as they attempt to prop up the currency until an estimated $22.5 billion comes in from a record corn crop and the fifth-largest soybean harvest in Argentine history.

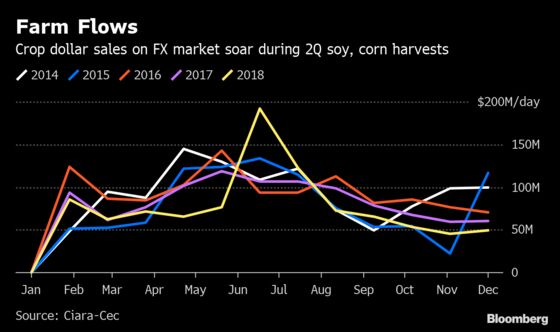

“It’s clear that the rhythm of farmer selling is more cautious than usual,” said Gustavo Idigoras, head of the Ciara-Cec crop export and crushing chamber, whose members include the so-called ABCD giants of agricultural trading. “They’re speculating on the currency and prices in Chicago.”

Farmers have tied themselves into contracts with traders for 8.6 million tons of soybeans, or 16 percent of the crop. At the same time last year they’d made commitments for nearly a third of beans, according to government data. By the end of June, farmers may have sold just 30 percent of their soy, said Agustin Tejeda, chief economist at the Buenos Aires grain exchange.

Patriotic Duty

The central bank’s predicament has revived a long-running debate about whether growers have a patriotic duty to sell soy to shore up the peso -- and boost Argentina’s trade and fiscal balances -- rather than hoard beans in silo bags and grain elevators, where they become a personal savings account.

Dimo, the farmer, isn’t convinced. “Nobody’s going to sell as a heroic deed,” he said at a farm fair last week close to Rosario, a riverside city that’s Argentina’s hub for crop shipments.

Likewise, Ricardo Yapur, a grower with 3,700 acres in Pergamino, Buenos Aires province, said he’d sell just half of his harvest to pay off debts he took on to plant beans. After that, he’d turn over the rest to exporters “truck by truck” as bills arrive for things like his kids’ school fees. “It’s not speculating,” Yarur said. “It’s protecting my currency, which is grain.”

Heavy Debts

In any potential standoff with the central bank though, the farmers don’t hold all the cards. Following a severe drought last year, many were highly leveraged going into soy and corn planting. Now, they have to make good on those debt payments and fulfill grain-barter arrangements with seed, farm-chemical and fuel suppliers.

They also need to finance winter wheat and barley planting. That’s why commitments to sell corn -- expected to bring in $5.4 billion -- are strong, said the export chamber’s Idigoras. Farmers are already tied into contracts for 24 percent of the corn crop.

Moreover, the central bank has another source of dollars on the way. International Monetary Fund staff agreed Monday to give Argentina access to the next disbursement of a credit line, worth $10.9 billion. The Treasury will use the funds to finance the sale of $60 million a day on the foreign-exchange market starting in April. That’s on top of the $4.1 billion it will pay out in bond maturities on April 22 and May 7, further strengthening the peso. So farmers betting on a weaker currency may be in for a shock.

But there is one more twist -- Argentines’ propensity to dollarize savings in election years. Voters are already seeing their incomes squeezed after the economy shrank about 2.5 percent last year. Should former leader Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner surge in the polls on pledges to pivot away from President Mauricio Macri’s market-oriented reforms, faith in the peso could be undermined.

Bumper crops, cautious farmers, IMF loans and presidential elections are all combining to make the outlook for the peso anyone’s guess.

--With assistance from Patrick Gillespie and Alec D.B. McCabe.

To contact the reporters on this story: Jonathan Gilbert in Buenos Aires at jgilbert63@bloomberg.net;Ignacio Olivera Doll in Buenos Aires at ioliveradoll@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: James Attwood at jattwood3@bloomberg.net, Philip Sanders, Ben Holland

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.