Americans Start Adapting to Climate Change. They’re Doing It Wrong

Americans Start Adapting to Climate Change. They’re Doing It Wrong

(Bloomberg) -- Americans took a long time to decide that adaptation to the changing climate was an idea worth exploring. It’s taken only a short time for them to start doing it wrong.

Decisions on projects and infrastructure are being made not on the basis of what’s effective or sensible in the long-run. And as is often the case, the poorest citizens are bearing the brunt of bungled policies. That’s the conclusion suggested by research published last week in the journal Ocean and Coastal Management.

North Carolina’s low-lying eastern flank, bounded by a thin line of barrier islands, is experiencing rising seas at a rate of close to four times faster than the global average. The coast is home to a combination of military and industrial areas along with federally protected lands. It has both cities and open country, along with a variety of income levels and demographics. The mix makes it a useful bellwether for coastal adaptation.

Even as the pace of climate change accelerates, planners and emergency managers across the country still have time to make well-considered decisions. “Ideally, you’d want a leader to sit down and say, ‘Should we build a wall? Should we retreat? Consider all of the options,’” said A.R. Siders, assistant professor at University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center and lead author of the study on how North Carolina has dealt with the issue. “But that’s not really what happens.”

The research finds that adaptation projects “disproportionately benefit the wealthy and increase the vulnerability of poor and historically marginalized communities.”

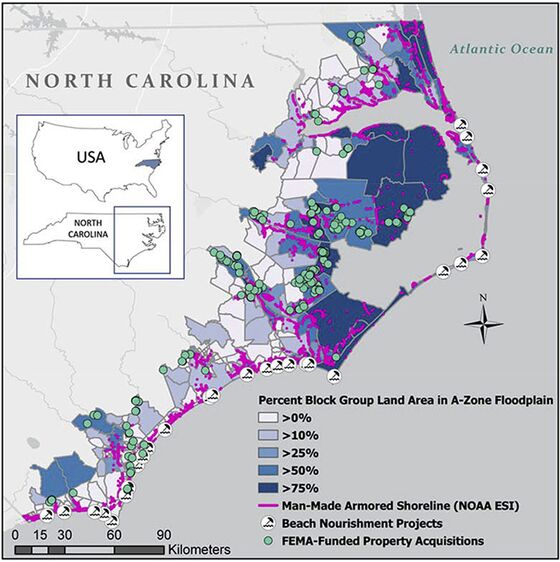

Some of what they discovered about wealth and adaptation had been predicted: Tax bases give local governments incentive to defend pockets of wealth against the ravages of climate change. According to the data, hardening shores and nourishing beaches have both been shown to correlate with higher property values.

Siders and co-author Jesse Keenan, a climate risk and adaptation specialist at Harvard, found a connection between wealth and protection. North Carolina communities on a river delta or a bay, like Belhaven or New Bern, they said, tend to have more buyouts, while relatively wealthier enclaves with oceanfront properties, like North Topsail Beach, resist them in favor of beach nourishment.

The authors looked at three kinds of climate adaptation measures: shoreline armoring, beach replenishment and flood-prone property buyouts funded by the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency. The pair wanted to know why officials make the choices they do among these three options—or take no action at all.

In the wake of a disaster, governments rush to provide funding for seawalls or relocate people, without more general discussions of strategy and options, Siders said. Broad conversations about large-scale adaptation generally don’t occur. This can lead to inefficient measures and spending. The researchers didn’t find any correlation between the type of infrastructure on shore and the type of protection chosen by a community.

It’s a shortsighted strategy. Along some of North Carolina’s barrier islands, communities are both armoring shores facing the bay and replenishing beaches facing the ocean. Under natural circumstances, barrier islands would push into the bay. Armoring the shoreline can halt that westward movement—but doesn’t stop the ocean from eroding beaches to the east. So, the barrier island, an already-thin strip of land, narrows and needs to be replenished with more sand.

Historically, the state has been “as good as it gets” in coastal management, so the situation “is probably going to be more dire in other places,” said Keenan. Only California’s coastal managers outperform North Carolina’s, he said.

As the economic costs of climate change rise, the lesson for the rest of the U.S. is clear, they write. Whether officials oversee oceanfront towns or flood-prone river communities inland, decision-making based on traditional bureaucratic and political practices may result in wasted public funds, while leaving vulnerable residents exposed.

“If left unabated, division between the haves and have-nots” will cause further problems, the researchers write, unless programs are designed “not just by what is efficient and effective, but also by what is fundamentally fair.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Joshua Petri at jpetri4@bloomberg.net, David Rovella

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.