The Fall of Juice and the Rise of Fresh Fruit

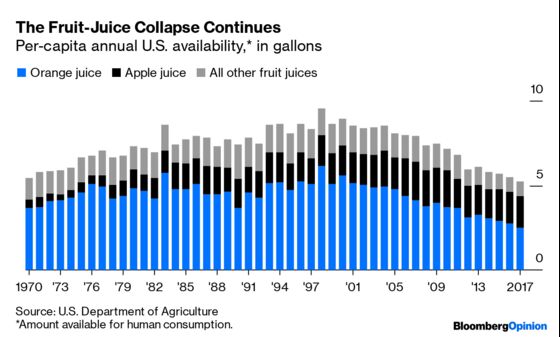

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Americans consumed 5.2 gallons of fruit juice per capita in 2017, according to data released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over the summer. Not exactly consumed — the USDA doesn’t follow people around watching what they eat and drink, so what it measures is “food availability,” which effectively means foodstuffs that are either consumed or wasted. In any case, this is the lowest fruit juice number since the USDA began tracking its consumption in 1970.

The rise and fall of orange juice is at the heart of this story. Consumption took off in the U.S. in the late 1940s, after USDA scientists figured out how to make frozen orange-juice concentrate that could be reconstituted into a palatable beverage. After that, advances in flash pasteurization brought not-from-concentrate juice that tasted even fresher, even though it usually wasn’t. For decades, OJ was successfully marketed as the healthy, vitamin-rich way to start the day. Then, around the beginning of the new millennium, it got caught up in a turn against sugar that swept through medicine and popular discourse. Blame for rising obesity and heart disease rates shifted from fats and meats to sugars and carbs.

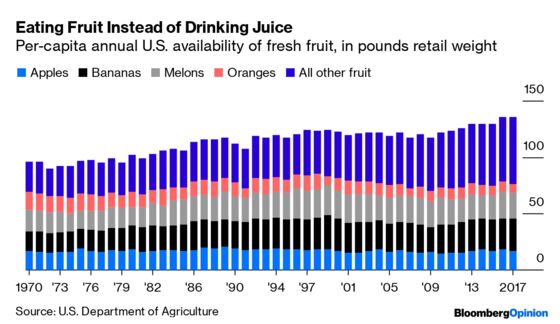

This anti-sugar turn stripped orange juice of its reputation as a health food. It and other fruit juices are now regularly derided as concentrated sugar-delivery mechanisms — and the once-mighty Florida orange-juice industry has been too wounded by hurricanes and citrus greening disease to fight back effectively. Whole oranges and other fruits are still considered healthy, though, and consumption of fresh fruit has been rising.

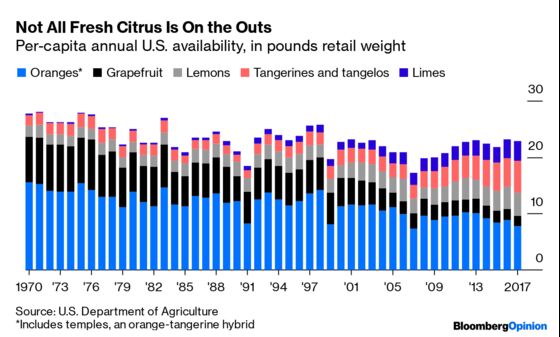

Once-rare treats such as avocados (yes, a fruit) and pineapples have become widely available, while California growers have figured out how to supply berries year-round. Avocados, grapes, pineapples and strawberries all now rival oranges in per-capita availability. Consumption of fresh oranges, which mostly come from California, is down, but not by as much as orange juice, and other citrus fruits are charging ahead: lemons, limes, tangerines and tangelos. Not grapefruits, though!

The spectacular decline in grapefruit consumption, from a peak of 9 pounds per capita in 1976 to just 1.9 in 2017, appears to have been caused mainly by a collision between older Americans’ breakfast preferences and their prescriptions. Grapefruit and grapefruit juice (per-capita consumption of which has fallen 89% since its 1978 peak) can interact in dangerous ways with medications for high cholesterol, high blood pressure and a variety of other ailments likely to afflict the elderly. So while I’ve been doing what I can in recent years to boost grapefruit demand (I’d guess I single-handedly consumed about 25 pounds last winter), it’s all over when I have to start taking Lipitor.

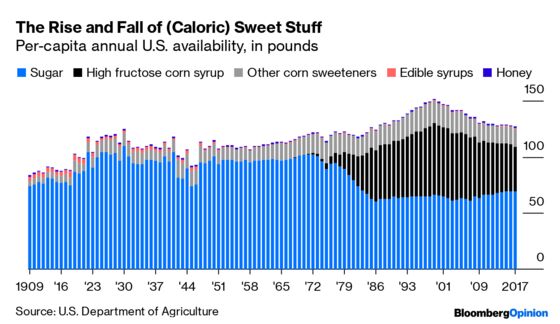

Also down is consumption of what the USDA calls caloric sweeteners — sugars, broadly defined.

One sweetener in particular has fallen on hard times. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup, which was promoted by the U.S. government in the 1970s as a way to (1) prop up demand for corn and (2) provide a cheaper way to sweeten soft drinks and other products, is down 38% from its peak in 1999. It has, probably undeservedly, acquired a reputation as the unhealthiest of sweeteners, which helps explain the slight rebound since the early 2000s in consumption of sugar proper. Overall consumption of caloric sweeteners is down 16%, which is a lot less than the 45% decline in juice consumption but still represents a big shift.

In 2013, for the first time since at least 1970, Americans consumed more fresh fruit than caloric sweeteners. In 2017, they consumed 8.3 pounds per person more fresh fruit. We are talking concentrated, mostly refined sweeteners versus fruits with peels, pits and the like, so the two aren’t exactly equivalent. The decline in consumption of caloric sweeteners has also slowed over the past decade, while the artificial sweeteners that have in many cases supplanted them — which the USDA does not track, but show big gains in surveys — aren’t necessarily always better. Still, this does seem like a remarkable triumph of science and scientific communication. A growing consensus that consuming lots of sugars (and by extension lots of fruit juice) was unhealthy has resulted in … less consumption of sugars and fruit juices.

These consensuses can shift, of course! Remember how eggs were bad for you and then good for you and then (as of the March 19 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association) bad for you again? There’s definitely been a modest backlash lately against the extreme anti-sugar view, but I haven’t really seen anybody arguing that we should be consuming more of the stuff. The U.S. may truly have passed peak fruit juice and peak caloric sweetener. That’s probably a good thing.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sarah Green Carmichael at sgreencarmic@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.