America’s Zombie Companies Are Multiplying and Fueling New Risks

America’s Zombie Companies Are Multiplying and Fueling New Risks

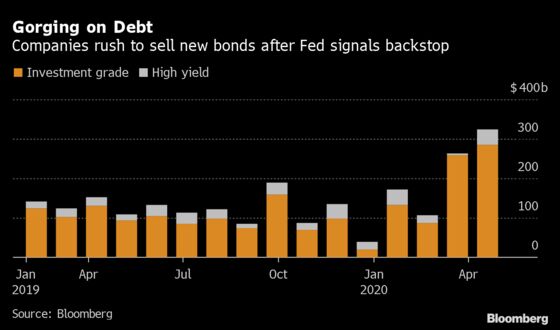

(Bloomberg) -- As the Federal Reserve pulls out all the stops to bolster credit markets, corporate America is gorging on debt.

From Carnival Corp., Marriott International Inc. and Delta Air Lines Inc. to Gap Inc. and Avis Budget Group Inc., many of the companies hardest hit by the coronavirus outbreak have priced billions of dollars of bonds and loans in recent weeks.

Never mind that profits have been wiped out, and that their business operations aren’t viable right now or likely anytime soon. As long as they’re propped up by the Fed, investors are willing to lend.

Yet as expectations of a V-shaped economic recovery vanish rapidly, more and more industry veterans are starting to express concern about these debt dynamics. Some warn that the Fed is putting credit markets on course for a future wave of defaults that makes the current stretch of corporate bankruptcies look timid by comparison.

Others see an outcome even more dire.

In this scenario, they say, moribund companies in industries deeply scarred by the pandemic will just keep borrowing. Market watchers such as Deutsche Bank AG chief economist Torsten Slok fear that a new breed of so-called zombie companies -- firms that don’t earn enough to cover interest payments and are kept alive in part by central bank largess -- could have profound and painful consequences for everyone from workers to investors for years to come.

“The Fed and the government are interfering in the process of creative destruction,” Slok said in an interview. “The consequence is that we are at risk the longer this persists –- companies being kept alive that would otherwise have gone out of business -- that it will begin to weigh on the overall potential for growth of the economy and on productivity.”

It’s not that these risks mean the Fed’s current policy tack is misguided. Given the scope of the economic collapse and the unprecedented spike in unemployment that has accompanied it, most analysts say policy makers had to throw everything they could at the problem. It’s just that such dramatic intervention comes with great risks that will have to be addressed down the road.

“The Fed had no other choice than to do what it did,” Slok said.

Still, it’s precisely this dramatic intervention that’s emboldening money managers to take greater chances and seek fatter returns.

“You can’t say ‘we’ll do whatever it takes’ and not do it,” said Jack McIntyre, who helps oversee about $60 billion at Philadelphia-based Brandywine Global Investment Management. “Otherwise, the Fed will lose credibility.”

McIntyre said he’s buying select investment-grade corporate bonds in lieu of Treasuries “because the Fed has backstopped the market -- if spreads widen, the Fed will step in.”

That’s just the sort of sentiment that can ultimately lead to the proliferation of zombies, economists say.

Fed Backstop

The actual definition of what makes a company a zombie varies depending on who you ask, but most agree that it’s generally meant to encompass firms that can’t cover their debt servicing costs from current profits over a select period.

A snapshot of the market reveals no shortage of companies that would fit that description should the economic rebound take time to gain momentum.

Earnings for companies, excluding financials, in the S&P 500 are forecast to drop a staggering 42% in the second quarter from the previous year as the full effect of global lockdowns are felt, according to estimates compiled by Bloomberg.

At the same time, net corporate debt issuance has ballooned, and could approach as much as $1 trillion this year, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Delta and Marriott declined to comment, while Avis didn’t respond to requests seeking comment.

Carnival referred Bloomberg to a press release highlighting the strength of its balance sheet and continued customer bookings for the second half of the year and 2021.

A representative for Gap directed Bloomberg to a statement noting its financing and cash preservation efforts, adding that the company plans to have 800 stores open by the end of May.

If the pace of the recovery is quick enough, corporate-bond buyers say plenty of hard-hit companies should be able to turn things around.

But the question on the minds of investors and economists alike is: how long will the Fed be willing to support firms via its pledge to buy corporate debt if the recovery is slower to develop than expected?

“The government has done more than I could have imagined to allow businesses to access capital, and if the markets shut down again the government will do even more,” said Bill Zox, chief investment officer of fixed income at Diamond Hill Capital Management, which manages around $19.5 billion.

Borrowing Binge

It’s an especially salient question when it comes to the sectors hardest hit by the Covid-19 outbreak.

Cruise lines have borrowed more than $8 billion via the bond market in recent weeks, selling notes secured by everything from ships to islands. Airlines, for their part, have gotten more than $14 billion in new financing from banks and investors, even as the vast majority of flights remain grounded.

“We have entire industries that are going to be protracted long-term if not permanently disrupted because of this,” said Vicki Bryan, a veteran credit analyst who runs Bond Angle LLC. “The cruise industry is ripe for elimination of companies. It should logically renounce the weaker players but that’s not happening because we have dirt-cheap money that we’re willing to throw back into the market from the Fed.”

Beyond just lending them money, creditors are also waiving or loosening financial markers on existing debt, allowing companies that have seen revenue dry up stave off potential tumult.

Vail Resorts Inc. -- owner of the eponymous winter vacation destination -- was granted a two-year reprieve on key debt covenants last month, paving the way for the company to raise $600 million with a new bond offering. Marriott, one of the world’s largest hotel chains, struck a similar agreement with lenders.

A representative for Vail said that the company’s bank covenant waiver provided additional flexibility given the short-term dislocation from Covid-19, and that it remains confident in the long-term outlook for both profit and cash flow.

‘Catch-22’

Yet amid the waivers, lenders are extracting higher interest rates or other concessions.

Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings Ltd., AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. and Avis all paid double-digit yields to borrow in recent weeks. That could depress their capacity to make capital expenditures and adapt to shifting consumer tastes as the coronavirus changes how people spend money.

“Taken together with margin contraction and leverage that was already near record highs, you may end up with a corporate sector that has less capacity to invest in growth,” said Noel Hebert, director of credit research at Bloomberg Intelligence.

Norwegian has a “long-standing track record of strong financial performance which includes over a decade of financial growth,” a company spokesperson said in an emailed response to questions. “The cruise industry has been hit the hardest by Covid-19 as our operations have been completely shut down, which certainly impacts us in the short-term but has no bearing on our long-term success.”

AMC didn’t respond to requests seeking comment.

Read more: Corporate debt loads are growing fast as Fed opens up spigots

Some say as successful as the Fed has been boosting credit-market liquidity, the support is only temporary, and will result in a wave of distress when it steps back.

“There will be plenty” of debt defaults and bankruptcies when corporate borrowers start running out of cash in the months ahead, Howard Marks, co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Group, said in a Bloomberg TV interview. “There are large, highly levered companies and investment vehicles that the government and Fed rescue program is not likely to reach and take care of.”

Others see central-bank intervention keeping companies alive for much longer, crowding out investment and employment at healthy firms, similar to what occurred in Japan during the nation’s ‘lost decade’ of the 1990s, where the ‘zombie company’ term was first applied.

“You are misallocating capital to businesses that are not productive and in some sense taking resources away from companies that have high growth,” Deutsche Bank’s Slok said.

The repercussions may only become apparent years from now, according to Marc Zenner, a former co-head of corporate finance advisory at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

“It’s hard for me to think that something like that doesn’t have a cost,” Zenner said. “What you’ll see is some of these costs will probably only emerge years later. Are we going to have reduced capacity to act? Is it that other economies will be less burdened and will attract more capital? Is there another crisis that will come because of this misallocation of capital?”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.