America’s Love Affair With Cheap Drugs Has a Hidden Cost

America’s Love Affair With Cheap Drugs Has a Hidden Cost

(Bloomberg) -- The day before Donald Trump was elected president, three federal inspectors arrived at Mylan NV’s manufacturing plant in Morgantown, West Virginia, and flashed their credentials. A tipster had raised concerns there might be unscrupulous activity at the factory where the generic giant makes some of its top-selling drugs. So, with Mylan executives looking over their shoulders in a conference room, the inspectors from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, dressed in button-down shirts and ties, began an intense two-week examination.

The team of chemistry experts sifted through thousands of random files containing what appeared to be forbidden exploratory tests, which some drugmakers have used to prevent quality failures from coming to light. The inspectors suspected Mylan laboratory staff had recorded passing scores on drugs that originally fell short of U.S. quality standards.

The files didn’t identify which drugs may have been involved in any exploratory tests. Instead they had obscure names like “lop” and “Medium”—and one that ended in LMFAO, a popular acronym for “Laughing My F**king Ass Off.”

The inspectors also found bins full of shredded documents, including quality-control records, in parts of the factory where every piece of paper is supposed to be saved. The list of alleged infractions became so long that a fourth inspector was added. A warning letter, the FDA’s strongest rebuke, was drafted. It would mean the agency could refuse to consider any Mylan application for a new drug made at that plant until the company fixed things.

But the warning letter was never sent. Eight months later in July 2017, higher ups at the FDA apparently decided to take it easy on Mylan, the second-largest generic drugmaker, with $12 billion in revenue in 2017. The FDA ultimately left it in the company’s hands, and the drugmaker promised to address what the agency calls a “data integrity” issue.

The FDA didn’t say specifically why it chose not to warn the company. “The FDA issues warning letters when it deems it necessary to take such action based on a combination of factors, including FDA inspectional findings, follow-up with companies and other factors,” said Sarah Peddicord, an agency spokeswoman. Mylan said it demonstrated to the FDA that the testing in question “occurred in the development environment and was not associated with commercial product.”

When Scott Gottlieb became FDA commissioner in May 2017, he made getting more generics to market a top priority so the extra competition would drive down drug prices, something President Trump had pledged to do.

Gottlieb’s actions on generic approvals have drawn praise from both parties in Congress, which is holding hearings on drug prices Tuesday. But with Democrats having taken control of the House, members who oversee the FDA say they plan to examine a crucial public-health question posed by his efforts: Is the fast-tracking of those approvals coming at the expense of oversight that’s supposed to ensure that drugs already on the market are safe and effective?

In a year-long investigation into FDA’s regulation of the generic-drug industry, Bloomberg examined hundreds of pages of inspection documents; reviewed more than 10 years of inspection data and thousands of pages of pretrial depositions; and interviewed more than two dozen current and former FDA inspectors and agency officials, lawmakers, and industry experts.

Concerns about quality control and data integrity have focused on numerous companies in India and China, where more and more drugs and active ingredients used in medicine for the U.S. are being made. But the interviews and documents suggest that those concerns aren’t limited to overseas factories. And the issues surrounding them are twofold: a drop-off in inspections in many places and, in some cases, the softening of penalties when problems are found.

Failures of quality control have also become a matter of dispute between generic-drug companies. Last month, the Delaware Supreme Court permitted the German company Fresenius SE to back out of its $4.3 billion takeover of Lake Forest, Illinois-based Akorn Inc. after Fresenius learned of a longstanding pattern of such problems in Akorn’s drug development and manufacturing systems.

In a taped deposition for the case, a pharmaceutical consultant testifying for Akorn said its issues are commonplace. “It is not unique to any one company,” said George Toscano, a data integrity expert at consulting firm NSF International who has done hundreds of drug-manufacturing audits. “It’s something that the entire industry is struggling with.”

In the face of such problems, the FDA approved a record 971 generic drugs in the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, according to a report from the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. That was a 94 percent increase over fiscal 2014, when 500 were approved.

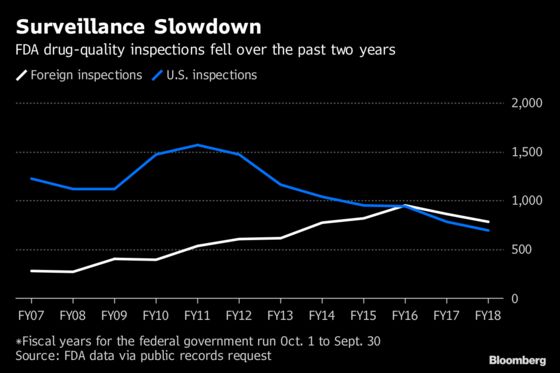

Yet the number of so-called surveillance inspections done globally by the FDA—meant to ensure existing drug-making plants meet U.S. standards—dropped 11 percent, to 1,471, in fiscal 2018 from fiscal 2017. Those inspection numbers also decreased in fiscal 2017, which included Gottlieb’s first few months in office, falling 13 percent from the prior year. The figures were obtained through a public-records request.

Surveillance inspections of just U.S. drug factories declined 11 percent, to 693, from fiscal 2017 to fiscal 2018, the lowest going back for at least a decade, the data show. Such inspections have been falling since 2011, as the agency began focusing more on foreign manufacturers.

Meanwhile, from fiscal 2017 to fiscal 2018, surveillance inspections of foreign factories fell 10 percent, to 778. This was the second year-over-year decline, after surveillance inspections of foreign factories dropped 9 percent from fiscal 2016 to fiscal 2017, reversing a trend of rising inspections over most of the previous decade. One marked exception to the recent drops: India, where inspections jumped 18 percent in fiscal 2018.

While inspections alone don’t ensure the safety of America’s drug supply, they are one of the few concrete measures available to assess FDA’s oversight. Even among agency veterans, there is strong disagreement over what the recent declines in inspections means.

Gottlieb and others say it reflects a smarter, more surgical approach. “It’s not the number of inspections we do, it’s whether we’re targeting effectively,” he said.

Industry proponents and the FDA say it decides which facilities to inspect using a risk score calculated by the agency. They also say that the FDA can’t inspect its way to better quality drugs, particularly with the limited resources it’s given, and that it’s up to drugmakers to police themselves.

But others, including Margaret Hamburg, the FDA commissioner under President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2015, see cause for concern, given the sprawling complexity of the system delivering more and more of the drugs that Americans consume. “Maintaining, if not increasing, inspections would seem crucial, given the global sourcing, supply chain, increase in approvals and quality issues,” Hamburg said after Bloomberg shared the inspection numbers with her.

Lawmakers shown the figures expressed similar worries—that the recent figures could reflect the agency putting approvals above enforcement. This was particularly true in the case of China, where FDA inspections fell almost 11 percent even as U.S. regulators oversaw a massive recall of a Chinese-made heart drug contaminated with a possible cancer-causing chemical.

“Any actions by the FDA to prioritize expediting drug approvals over ensuring manufacturing quality and compliance would be concerning, as it has the potential to risk patient safety,” said Representative Frank Pallone, the New Jersey Democrat who is the new chairman of the House Energy & Commerce Committee, with jurisdiction over the FDA. “I look forward to hearing more from the agency about how they are balancing both missions.”

To patients in the U.S., the origin of their drugs shouldn’t make a difference. Whether treatments are made in West Virginia or Mumbai, they’re supposed to meet FDA standards for safety and efficacy. But as the industry has become increasingly global and desire for lower drug prices continues to grow, signs are indicating that U.S.-made drugs aren’t immune from the same forces that have led to corner-cutting overseas.

The FDA’s current approach was mandated by a 2012 law. To determine when to visit a facility, the agency takes into account when the facility was last inspected, what that most recent look found and what the plant manufactures, among other factors. The agency sends inspectors to facilities with the highest risk scores first.

“There’s things that go wrong that are hard to predict,” Gottlieb said. “But there’s certain actors that are more likely to make mistakes that present public-health challenges. And there are certain actors that are more likely to do something deliberate—and those are the ones that you need to be focused on.”

Congress focused on drugmaker inspections after a 2008 crisis in which a contaminated blood thinner called heparin made in China was linked to more than 200 deaths in the U.S. Lawmakers used the 2012 law to boost the FDA’s ability to inspect foreign drugmakers.

Today, 90 percent of the medications that Americans take are generics. They’re cheap because they rely on research done by brand-name pharmaceutical companies. When a brand-name drug’s patent protection runs out—generally after about 20 years—a generic firm can copy the product. The maker only has to prove it works the same as the original, saving hundreds of millions of dollars on research and development.

Those savings are typically passed on to the patient who, after several generic versions of a single drug hit the market, will pay up to 80 percent less. The more generics competing against each other to sell a single drug, the lower the price; hence Gottlieb’s push to get more of the copycat drugs to market.

Prices remains a key interest of the Trump administration, and in recent weeks Congress has introduced several bills to contain them.

The issues with data integrity at companies in India and China—and now in the U.S.—raise questions about whether the drugs actually work the way they’re intended.

There’s no easy way to measure the scope of the problem. Drugs are recalled every day for various reasons. Cases of contamination are sometimes easier for distributors or patients to spot. With other issues, including the rate a drug dissolves in the body or whether a medicine contains enough active ingredient, the FDA typically counts on the drugmaker to identify a problem and then relay it to the agency.

In fact, the FDA doesn’t test finished drugs or ingredients regularly, relying heavily on company testing. If manufacturers are omitting data that show quality testing failed, that information might not get to the FDA.

An online-pharmacy startup in New Haven, Connecticut, called Valisure tests the medications it dispenses. Since opening last year, it has screened about 100 drugs and found that more than 10 percent didn’t have the proper amount of active ingredient or didn’t dissolve as they should, according to David Light, Valisure’s chief executive officer.

In the case of Mylan’s West Virginia facility, the FDA inspected again in 2018, in March and April. Inspectors made a list of 13 alleged violations, including that Mylan’s manufacturing equipment wasn’t cleaned at appropriate intervals to prevent contamination. Inspectors also found that Mylan’s attempt to address the purported violations involving prohibited trial testing from the agency’s November 2016 visit was “not adequate,” though the reasons why are redacted from inspection documents.

In its earnings statement issued in November, Mylan said it had committed to a “restructuring and remediation program” to reduce complexity at the site by decreasing the number of products made there and reducing the workforce. Four days later, the FDA sent Mylan a warning letter for its West Virginia plant. This time, the agency told the company to hire a manufacturing consultant to help the plant improve its standards.

“We are working closely with the agency to resolve all of their concerns,” Mylan said in an emailed statement. “The facility continues to manufacture currently approved products while we are executing on our commitments to FDA. Mylan is committed to maintaining high quality standards, and we take very seriously our continued and comprehensive oversight of our entire manufacturing network.”

Mylan also said the FDA conducted 21 inspections at its almost 50 facilities around the world in 2018. The company sells more than 7,500 brand-name and generic prescription drugs and over-the-counter treatments.

Data integrity was also at the heart of FDA inspector concerns at a plant halfway across the world, where Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. was supplying the active ingredient valsartan—a widely used treatment for high blood pressure that is taken alone, as well as sold in combination with other cardiovascular drugs—for major pharmaceutical companies such as Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., the largest generic drug maker in the world.

The inspection in May 2017 found that the Chinese ingredient maker ignored quality checks that showed unnamed drugs didn’t meet U.S. standards. Four months later, higher-ups at the FDA once again overrode the concerns of those on the ground who wanted to slap Zhejiang Huahai with harsher penalties. Instead, the agency gave the company a chance to fix its problems.

Jun Du, chief executive officer of Zhejiang Huahai subsidiary Prinston Pharmaceutical Inc., said it has been in close contact with the FDA about valsartan and has “collaborated throughout with agency staff, our customers and patients.” Prinston used its parent company’s active ingredient to make its valsartan, which has been recalled.

More than a year after the inspection, numerous drug companies recalled valsartan, including Teva, for containing a probable cancer-causing chemical. Teva has since stopped selling the drug.

The FDA says the U.S. has the safest drug supply in the world. But even anecdotal cases of such problems undermine a core assumption about the practice of medicine: that the drugs a doctor prescribes are safe and effective. Even an inkling of doubt about a drug’s quality makes a physician's job that much harder.

Harry Lever, a cardiologist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, has been particularly wary of drugs made in India and China for several years. As a physician, he often has no control over which generic drugmaker is used to fill a prescription. Many times, when he has a patient who isn’t improving or whose condition has worsened, he asks them where their drugs are made.

One of those patients, Dick Farrell, had open-heart surgery in 2015 and had been doing well until last year. The former reporter and editor from Dover, Ohio, started having trouble with simple tasks like walking from the parking lot to the grocery store. He was admitted to the Cleveland Clinic in April with congestive heart failure. Soon after, Lever asked him to check whether his diuretic, called torsemide, was made in India.

It was. Farrell had been taking torsemide made by Hikma Pharmaceuticals Plc, a London-based drugmaker, and was switched by his pharmacy benefit manager to the Camber Pharmaceuticals Inc. version of torsemide in either late 2017 or early 2018. Closely held Camber repackages drugs made by Indian drugmaker Hetero Labs Ltd., which was warned by the FDA in 2017 for failing to adequately investigate test results that showed products didn’t meet U.S. standards and for not properly cleaning and maintaining equipment.

The FDA’s warning to Hetero doesn’t identify specific drugs because the agency typically redacts drug names to protect trade secrets and can’t reveal where a drug is made, except under special circumstances.

At Lever’s urging, Farrell called 10 different pharmacies nearby and found one that sold torsemide made by Israel-based Teva, which has factories all over the world, including in India, Hungary, China and the U.S. (It’s unclear where Farrell’s new medication was made.) Despite changing medication, he never fully recovered, dying in September at age 67, about a month after celebrating his 40th wedding anniversary.

There’s no proof the Indian-made torsemide was ineffective and led to his death. But his physician is now more concerned than ever. Lever thought it was bad enough when quality issues appeared to be an overseas problem. He was shocked to learn companies in the U.S. have been caught with data integrity problems as well.

“I’ve been smelling rats,” Lever said. “I didn’t realize there were that many.”

Camber confirmed in an email that Hetero’s torsemide is made in India and said the plant that makes the drug was inspected in the last six months and the FDA didn’t find any violations.

“Hetero and Camber manufacture and distribute almost 100 million torsemide tablets per year (a billion since its approval in January 2009) and a quick review of our records shows a total of three complaints in the last year,” said Kirk Hessels, a spokesman for Camber.

Indian companies accounted for 38 percent of approvals in 2018 through October 30, up from 33 percent in 2015, according to senior Moody’s analyst Morris Borenstein. Over the same period, Chinese drugmakers accounted for 8 percent of approvals, up from 1 percent, Borenstein said.

These numbers don’t include companies in India and China where active ingredients for drugs are made, because most drugmakers keep secret where they buy such key building blocks. At least 80 percent of active ingredients used to make U.S.-consumed drugs are produced outside of the country, according to the FDA. In the rare instance an active ingredient’s origin does become public, it’s typically because of a serious recall, as in the case of valsartan.

The FDA has come a long way since the heparin crisis of 2008, when Congress went after the agency for not knowing how many foreign facilities were even making drugs for Americans to take.

“I think our oversight is better than it’s ever been,” said Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA center responsible for overseeing new drug approvals who has served at the agency in various capacities since 1986. “That’s my professional judgment of manufacturing worldwide. We know where they are, we know who they are, we know what they’re making, we know when we’ve been there, we know who else has been there. Could we improve? Yes, but I wouldn’t look at absolute stark numbers and say that should be a greater or lesser cause for concern.”

Woodcock pointed to an agreement with the FDA’s counterparts in the European Union as one of the reasons that surveillance inspections could be going down. The deal lets the FDA rely on EU inspections in European countries instead of duplicating the work. But the deal took effect only in November 2017, after the surveillance numbers started falling, and the agreement doesn't cover India or China.

Democratic and Republican lawmakers alike worry the FDA may be backsliding on quality control just as it’s approving more generics.

“These are serious concerns that warrant further investigation, and we expect that the FDA will provide us with additional information and analysis,” said Oregon Representative Greg Walden, a top Republican on the Energy and Commerce Committee.

Representative Diana DeGette, a Colorado Democrat who chairs the House’s investigations subcommittee with oversight of the FDA, said regular and timely inspections are necessary to hold manufacturers accountable.

“Americans need to know that their medications are safe and effective,” said DeGette. “And it’s the FDA’s job to ensure that, from the factory floor to the shelves of our pharmacies.”

—With assistance from Jef Feeley

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Flynn McRoberts at fmcroberts1@bloomberg.net, Timothy Annett

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.