Airport for Sale Tells a Tale of $140 Billion Turkish Overreach

Airport for Sale Tells a Tale of $140 Billion Turkish Overreach

(Bloomberg) -- The operator of a provincial airport in western Turkey is putting it up for sale in a rare indictment of a system of public-private partnerships that are hobbling the nation’s finances.

Closely held IC Ictas, which entered into a partnership with the government nine years ago to build and operate Zafer Airport, is waiting for offers following a slump in passenger use, according the airport’s chairman, Abdullah Keles. Built at a cost of more than 50 million euros ($59 million), Zafer, located about 374 kilometers (234 miles) south of Istanbul, has seen traffic all but disappear amid the pandemic. In the last year before the virus erupted, it registered little more than 6% of the 1.3 million passenger target level below which IC Ictas is entitled to government guaranteed payments. The number barely rose above 7,000 this year.

“We are ready to transfer the airport to any party that will pay us what we invested and assume the debt,” Keles said in an interview from Istanbul.

Critics say Zafer’s failings are symbolic of how Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government has frittered away taxpayers’ money through a $140 billion drive to build everything from roads to power plants and hospitals based on public-private partnerships that too often create so-called white elephants and leave operators out of pocket. Worse, when breakeven targets are missed, it piles a burden on Turkey that it can ill afford.

Ugur Emek, a former official at the now-defunct State Planning Council, says a calculation of contingent liabilities -- a method used by the IMF to consider worst-case scenarios -- shows Turkey would face a bill equivalent to a fifth of its $729 billion economy if the projects generated zero traffic over the next quarter century.

While that’s a theoretical outcome, the difficulties the projects pose will still be with Turkey for years to come, he says.

“They’re damaging the operational capacity and budget room of incoming governments,” Emek said in an interview from Ankara, where he is a professor of economics at the city’s Baskent University. “Even today, payments related to city hospitals comprise a third of the Health Ministry budget.”

Examples of other money-draining projects are legion. The government had to fork out about 2.2 billion liras ($250 million) in guarantees last year to the operators of the 250-mile North Marmara Highway, which runs from Istanbul to Sakarya province, according to Haberturk newspaper. It paid out 1.6 billion liras in the second half of 2020 for the Gebze-Izmir Highway, which connects Istanbul to the Aegean port of Izmir, the paper also said. And the opposition Republican People’s Party says Turkey is due to pay three times over the odds for power from the Russian-built Akkuyu nuclear plant when it’s completed over the next few years.

Erdogan’s AK Party stands by its approach. The government will “continue to defend these public-private partnership projects,” said Yasar Kirkpinar, a ruling-party member who sits on the parliament’s budget commission. Zafer Airport represents a “minuscule” part of a system in which 70% of the projects are successful, he said.

Infrastructure Bonanza

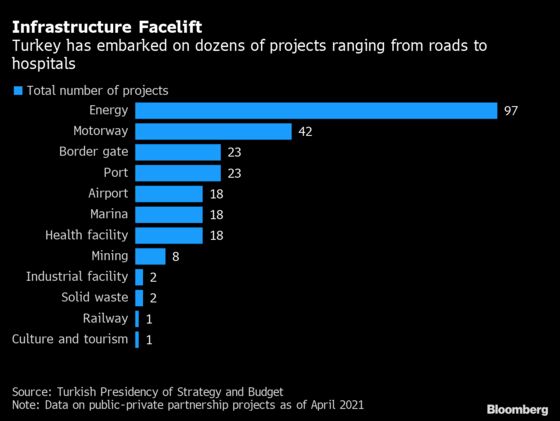

Since Erdogan became prime minister in 2003, Turkey has rolled out 181 public-private partnership projects, official data show. More than half are modeled on the build-operate-transfer system, and many entail state payment guarantees based on upbeat projections about future use over periods typically measured in decades.

Turkey has budgeted for 30 billion liras ($3.5 billion) of such payments this year, according to Emek, an amount he says will likely be higher due to the lira’s depreciation. The currency has weakened about 11% versus the dollar this year.

For a government whose balance sheet remained resilient even as the country has lurched from crisis to crisis, a lack of transparency over its contingent liabilities remains a worry. The IMF has called for more information about its “quasi-fiscal operations” and urged greater oversight of the partnerships.

Estimated at almost $600 million per project, the partnerships have reached the highest average investment size among all emerging nations. Other commitments, including those from the government-backed Credit Guarantee Fund, could put even more strain on state finances.

“Although the official public debt ratio is comparatively low, the potential cost of contingent liabilities which result from quasi-fiscal measures put upward risks on debt sustainability,” the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said in a January report.

Back at Zafer, which means “victory” in Turkish, the mood is anything but triumphant, as locals shun it in favor of other airports closer to sightseeing centers such as Eskisehir, 113 kilometers away, says Keles.

“Our group hasn’t received a dime from Zafer to this day,” he said. “On the contrary, we are forced to inject fresh capital into it every year” despite the state guarantees.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.