‘Post-Chemical World’ Takes Shape as Agribusiness Goes Green

‘Post-Chemical World’ Is Taking Shape as Agribusiness Goes Green

(Bloomberg) -- Agribusiness is increasingly turning to natural and sustainable alternatives to chemicals as consumers rebuff genetically modified foods and concerns grow over Big Ag’s role in climate change.

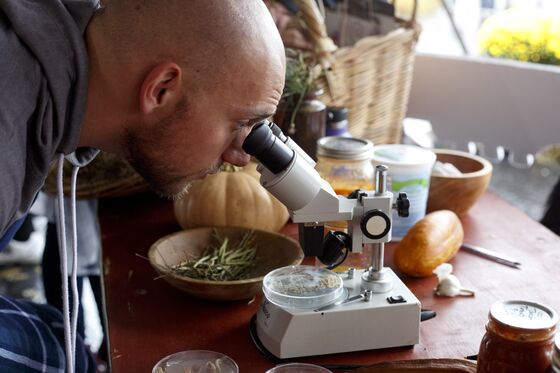

At the heart of the trend are innovations that harness beneficial microorganisms in the soil, including seed-coatings of naturally occurring bacteria and fungi that can do the same work as traditional chemicals, from warding off pests to helping plants flourish, according to a global patent study by research firm GreyB Services.

“Both entrepreneurs and investors are saying, ‘Hey, the writing is on the wall, we’re entering a post-chemical world,’” said Rob LeClerc, chief executive officer of AgFunder, an online venture-capital platform. “The seed companies who have billions in market cap are like ‘We need to do something,’ and everyone recognizes the opportunity.”

Much of the handwringing over farm chemicals stems from the recent fate of glyphosate, the most ubiquitous weedkiller ever. Regulators around the world are tightening up rules around using the chemical, including Europe and Mexico. Meanwhile, thousands of lawsuits that could result in billions of dollars in penalties are pending against Bayer AG over whether its glyphosate-containing product, Roundup, caused cancer. Bayer insists it’s safe, and some government agencies such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency say it isn’t likely to cause cancer in humans.

The global fertilizer and pesticide market is around $240 billion, and grows 2% to 3% a year, according to Ben Belldegrun, a managing partner at Pontifax AgTech, a company that invests in food and agriculture technology. While so-called biologicals including biofertilizers, biopesticides and biostimulants are just 2% of that market, those have been growing closer to 15% a year for the past five years, Belldegrun said.

As population increases worldwide, the demand for agricultural products is projected to grow 15% over the next decade with no change in the amount of land available for farming, according to a joint report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

“There’s a growing world population and how are we going to feed all of these people?” asked Craig Forney, assistant director for licensing and business development at Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. “At the same time, we want to protect the environment. We need to use land better and use the resources better.”

The answer, Forney said, is “intensified agricultural production to increase productivity of land and do it with minimal chemical support.”

Patents give owners the exclusive right to an invention, and can indicate both where research funding is being spent and where companies or universities expect to generate revenue in the future.

Companies like BASF SE, Bayer and Syngenta AG have patents on products using naturally-occurring microbes to help crops flourish even when there is low water availability, according to GreyB’s analysis. The microbes can act as catalysts to encourage growth. Biological-based fungicides and insecticides can also help reduce crop damage from insects, slugs and fungi.

“Seed-applied biological products can extend the window of disease and pest protection, while some also provide alternate modes of action that can reduce the build-up of resistance, aid with nutrient management and reduce plant stress,” said Chris Judd, BASF’s global strategic marketing manager for Seed Treatment, Inoculants and Biologicals.

Evonik Industries AG, Altair Nanotechnologies Inc., Covestro AG and startup Indigo AG have been active in obtaining patents and publishing research in the area of using microbes, as have universities like China’s Zhejiang University and Nanjing Agricultural University, according to GreyB.

Likewise, thousands of patents are being issued to companies like BASF, Bayer and Dow Inc. for more natural ways of managing pests including pheromones that deter breeding and reflective mulches, instead of chemical-based insecticides.

Germany’s Bayer, which bought agriculture chemical giant Monsanto Co. in 2018, sees “high growth potential” for biologicals, citing a challenging regulatory environment for chemicals and a growing emphasis on sustainability in agriculture. Bayer has a research and development team solely focused on them. The company also is hunting for partnerships to boost its portfolio. Benoit Hartmann, head of biologics at Bayer, said the increased investments show how the science around microbes has matured in recent years.

In 2013, BASF acquired seed-treatment supplier Becker Underwood, which helped the company become a leader in biological agents to fight bacteria and fungi. Judd said the company sees demand for biologicals increasing but maintains that they need “to be compatible with an increasing array of chemistries and to have the ability to survive on the seed for adequate periods.”

The increased patenting reflects a trend of researchers looking for ways to help promote organic and non-GMO farming, said Nicole Kling, a patent agent with Nixon Peabody who specializes in the biotechnology field.

With biologicals, “You’re not introducing chemicals with the scare quotes around it,” Kling said. “You’re not doing anything that would harm the agricultural workers.”

Researchers and companies are looking for new solutions for farming with less chemicals because organic farming, the most popular alternative to modern conventional farming, often results in lower yields. Still, demand for food continues increasing. Iowa State and other universities around the world, using government funding or in partnership with companies, are rushing to deal with those competing demands.

“The hope is someday in the future they will merge and you will have organic and non-GMO products that are just as productive as Big Ag,” Forney said.

That’s where things like precision agriculture to tailor the application of nutrients, artificial intelligence to monitor soil conditions and the development of new plant hybrids come in.

Other emerging techniques that could boost yields while helping farmers use less chemicals is artificial intelligence, which is being used to analyze which seeds and crops can yield the most based on changing soil conditions and weather patterns on a farm. The promise of quantum computers would let companies use massive computing power to develop and analyze new seeds and fertilizers.

Scientists also are developing new plant varieties, with applications for new varieties up 9% in 2018, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization. China led the growth, with more than a quarter of the applications for new varieties.

Much of the research in crop biotech is centered in the U.S., China, Germany, Japan and South Korea, though it’s being adapted to meet local conditions in Africa, Latin America and Asia, according to WIPO, an agency of the U.N.

Demand for more food will be greatest in Africa, India and the Middle East. In the developing world, there is little food scarcity because “we did good things with all that ‘better living through chemistry,’” Kling said, referring to a play on an old DuPont motto. It has come at a cost, though.

“We’re starting to see some of the effects of that -- all of this wonderful industrialization has contributed to climate change,” Kling said. “We’re starting to see people swing back in the other direction.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Lydia Mulvany in Chicago at lmulvany2@bloomberg.net;Susan Decker in Washington at sdecker1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jon Morgan at jmorgan97@bloomberg.net, ;James Attwood at jattwood3@bloomberg.net, Elizabeth Wasserman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.