After Archegos, Credit Suisse Is Gripped by Paralysis and Dread

After Archegos, Credit Suisse Is Gripped by Paralysis and Dread

(Bloomberg) -- Soon after he started at Credit Suisse Group AG, Antonio Horta-Osorio compared the bank’s crisis to the pandemic. Like frontline workers in a country beset by Covid, he said, the Swiss giant’s staff needed to be selfless and put the company’s needs first.

Some bankers were unimpressed by their new chairman’s drawing of parallels between a deadly virus and a corporate emergency, but one similarity rang true: Credit Suisse felt like a place under lockdown.

The problem for Horta-Osorio is that he’s been in the post six months now and that feeling persists. Following two financial humiliations early this year — the implosions of Greensill Capital and Archegos Capital Management — a state of near-paralysis has seized parts of the bank. Routine transactions that would have been waved through are being held up by skittish managers. Messaging from the top has been patchy, failing to stem an exodus of talent.

Horta-Osorio, who arrived in Switzerland with a reputation as a corporate lifesaver after rescuing Britain’s Lloyds Banking Group Plc, has promised to deliver his plan to fix Credit Suisse by the end of the year. In the meantime, some of the firm’s upper ranks have been canvassing support in case there are disagreements about the direction set, according to people familiar with the bank. A company spokesman declined to comment on all the points raised in this story.

For AHO, as he’s known to some, Credit Suisse is the challenge of a lifetime. The recent roll of dishonor at the 165-year-old Swiss institution is long and varied: There’s the ruinous ignoring of risk on Archegos and Greensill; the spying on executives; the fund-raising scandal in Mozambique. The cultural rot runs deep.

But for the firm’s 48,000 or so employees, the wait for his strategic reboot is agonizing. The axe is being sharpened for the troublesome investment bank, blamed by many for the company’s ills, and people there are on tenterhooks. They wonder which of its constituent parts will survive and which will be starved of capital. One question for the chairman as he fine-tunes his plan is, What’s taking so long? Staff hope to see some details or hints in next week’s quarterly earnings update.

Bank Adrift

Conversations with a dozen bankers in different parts of Credit Suisse and at different levels of seniority, who would only speak anonymously to Bloomberg News when discussing company matters, reflect the grim mood. They talk of uncertainty about what the business will look like next year, flagging morale as workers look for word from on high, and a lack of trust between colleagues.

There’s hope, too, that Horta-Osorio — who’s walked trading floors, chaired town hall meetings and held fireside chats at Credit Suisse offices worldwide — might set the right course finally after years of poor navigation; and there’s some acknowledgement that this salvage mission can’t be rushed. But he hasn’t been paying enough attention to how the stasis is affecting staff, several company veterans say. Some bankers have written off 2021 and plan to coast into 2022. Provided they don’t jump ship first.

At a recent investor meeting the chairman said his team was “working relentlessly” on delivering the new strategy, one that would set a path through the Archegos and Greensill wreckage. Internally, this urgency hasn’t always been communicated clearly.

In a brief memo to staff on Aug. 30, Horta-Osorio and Chief Executive Officer Thomas Gottstein wrote that they’d been working to “narrow down our options” on the strategy. Many employees were nonplussed that they’d only just reached that stage.

The chairman and CEO hadn’t been twiddling their thumbs: They’d been occupied with an X-ray analysis of the Archegos fiasco. Nevertheless, the memo’s lack of detail was jarring. Horta-Osorio had been in the post four months by then; Greensill and Archegos blew up in March.

The sense of drift hasn’t lifted since the summer. While an excoriating report on the $5.5 billion Archegos losses was published in July, another on the Greensill debacle has been delayed. Much is unresolved.

Crucially, the chairman has the backing of shareholders, including the bank’s biggest. David Herro of Harris Associates says Horta-Osorio, a tough-minded and astute 57-year-old with dual Portuguese and British citizenship, has the management chops needed to clean up the mess. “I am very, very gratified that the person at the top of the organization is extremely capable and has a good understanding of risk,” he told Bloomberg TV this month. Herro was no fan of Horta-Osorio’s predecessor, Urs Rohner.

The clock is ticking, however. “The disappointment of not doing anything, it becomes costlier and costlier over time,” says Arturo Bris, a finance professor at Switzerland’s IMD Business School. “It’s exponential. There’s a time limit — six to nine months — in which customers, investors and employees need to see something happening.”

Profit Squeeze

A capital squeeze on parts of the investment bank, especially the prime-broking unit that provided leverage to Bill Hwang’s Archegos, already seems to be taking a toll, as does the departure of many dealmakers. Competitors are happily stepping into the breach.

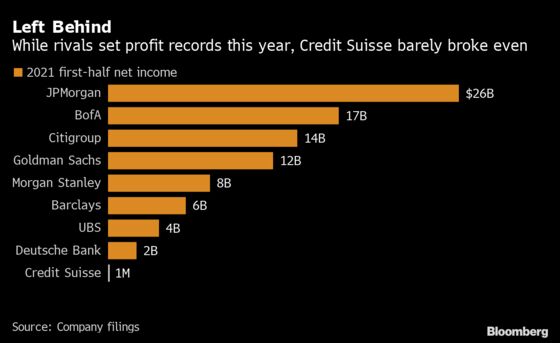

As Credit Suisse stares at a lost year of profit, its closest Wall Street rivals are making merry amid a boom in equity trading and M&A. Citigroup Inc.’s stock-trading and investment banking revenue both jumped by about 40% in the three months to September, and Bank of America Corp.’s by a third and a quarter. “We do expect at least some of this relates to banks picking up share from Credit Suisse,” says Alison Williams, a senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

Despite the complaints of torpor among the troops, Horta-Osorio has been busy assessing the officer class. In recent months he’s been parachuting in old allies from Lloyds and veteran bankers from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. to fill important roles. And he’s been weighing up whether the makeshift crew of caretakers that runs Credit Suisse’s divisions is fit to execute a turnaround. Of its five units, four are run by people appointed after a surprise departure.

That status is shared by Gottstein, a company lifer catapulted into his position in Feb. 2020 when Tidjane Thiam left after the spying scandal. The chairman says his CEO has the “full support” of directors. While some shareholders say privately that they aren’t convinced Gottstein should be in the job for the long term, they’re willing to back Horta-Osorio’s judgment.

Away from the C-Suite, most employees are just trying to divine the future under their new chairman. Go too far in reshaping the bank, and stamping on risk, and he might threaten its future profitability. Not far enough and he’ll be accused of rearranging deck chairs on a leaking boat.

Merger Talk

There’s been chatter about hiving off the investment bank, or even a full merger of Credit Suisse with a competitor. Rumors are circulating that a big New York rival might attempt a knockout bid, though a tie-up with Swiss compatriot UBS Group AG may be more palatable politically.

Herro says such talk is premature. “Picking apart” the bank isn’t the right thing to do without allowing the chairman time to restore order, he said. “There’s no reason why Credit Suisse can’t exist as it exists today but with improvements.”

Horta-Osorio didn’t soothe investment banker nerves back in June, when he said the firm had a great wealth management business, “with ancillary services.” But investors and employees anticipate surgical strikes on the unsalvageable parts of the investment bank, rather than a nuking of the whole thing. Workers there, especially traders, are braced for a reduction in their numbers and more deep cuts to their capital usage, as well as a pullback from riskier areas such as credit. Some capital-hungry teams such as leveraged finance are highly profitable so they may be spared.

Citi analysts wrote recently that they expected the restructuring to home in on the investment bank’s trading operation, “which has generated subpar profitability for years.” They expect Credit Suisse to become ever more dependent on its prize asset: the private wealth unit.

That business, which contributes about 70% of Credit Suisse’s net revenue, could use a shot in the arm. Its staff complain that they’ve been paying the price for failures elsewhere. It was the prime-broking unit that engaged so recklessly with Archegos, and it was the asset-management arm — also now subject to discussions about its future — that had to freeze $10 billion of supply-chain finance funds linked to ex-billionaire Lex Greensill. Those funds were sold primarily to the bank’s wealth clients.

According to some of the firm’s private bankers, rich clients are asking: How can we trust that this other product isn’t more of the same? Billions of dollars of wealth assets walked out the door in the second quarter. “If you have another quarter of weak outflows, investors will worry,” says BI’s Williams. “That’s the crown jewel.”

Other successful parts of the company have suffered, too. The M&A business has been a marquee name going back to when the investment bank was known as Credit Suisse First Boston. But more than 60 senior dealmakers have left since Archegos and Greensill imploded.

In a banner year for M&A, rivals can afford to offer lavish pay packages. Can Credit Suisse? It’s a question not limited to the deals team.

Prime Cuts

Even the shrinking of culpable divisions will hurt. After the Archegos disaster, Credit Suisse said it would reduce the prime brokerage’s lending to hedge funds by a third. Its balance sheet has been cut by about half instead, according to a person with knowledge of the business. With such a drastic downsizing, staff — and clients — wonder whether the prime-services unit will be closed altogether or the remaining parts sold. They worry about collateral damage to more cherished businesses such as equities and M&A.

This year’s woes will likely mean that, for many, the 2021 bonuses they were counting on won’t be forthcoming. Some fret there will be little room for raises next year or the one after. It’s against this backdrop that Horta-Osorio must put the finishing touches to his master plan, and find a compelling reason for gifted bankers to want to work at the Swiss giant.

Starting from such a low base might help. One shareholder says the chairman needs a strategy that’s carefully targeted, time-bound and capital efficient — not an outrageous ambition given this year’s shambles. With the stock trading at less than 60% of Credit Suisse’s book value, some analysts don’t ascribe much value to the investment bank. Even marginal improvements will make a difference. And younger bankers are getting the chance to step up as more established stars head for the exit.

Plus the savior of Lloyds has accrued plenty of goodwill over the past decade. Some see him as the Swiss bank’s last best hope. “I cannot think of a plan B after Horta-Osorio,” says Bris at the IMD Business School. If he were to find the task too daunting and move on eventually, “This would really be the beginning of the end for Credit Suisse.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.