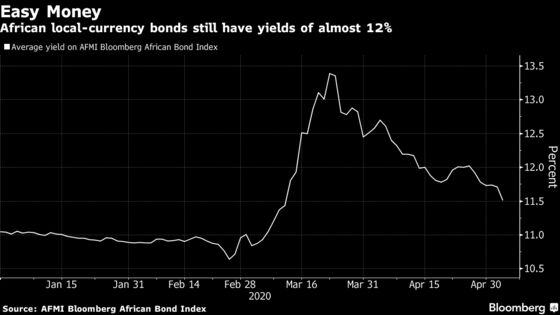

African Banks Find Solace in 12% Bond Yields as Loans Dry Up

African Banks Find Solace in 12% Bond Yields as Lending Dries Up

(Bloomberg) -- Measures by some African countries to get money flowing into the real economy aren’t working yet, with banks parking cash in government bonds as the economic slowdown cuts demand for credit.

Lenders have little choice but to invest in government securities as opportunities to deploy unprecedented amounts of liquidity provided by their central banks dry up. Lockdowns aimed at containing the spread of the coronavirus have brought trade to a halt, leaving lenders to focus on helping existing customers with payment holidays or loan restructurings.

“In this kind of environment, where you have weak economic activity and high risk profile, it is very difficult to grow your loan book,” said Omotola Abimbola, an analyst at Chapel Hill Denham in Lagos. “Many banks will want to preserve their capital by taking as little risk as possible and then invest in government securities.”

Read more: African Banks Snap Up Government Bonds as Foreigners Flee

Central banks in South Africa, Kenya, Ghana have released billions of dollars from lenders’ balance sheets by easing measures on how much capital lenders need to set aside.

Deep interest-rate cuts means banks make less money on loans, while rising impairments and a reduction in fee and transaction income will also weigh on lenders’ earnings, Moody’s Investors Service said in an email.

“At best, profitability will stay flat year-on-year,” said George Bodo, the chief executive officer of Callstreet Research and Analytics. “Credit risks were already elevated across the region. Covid-19 just exacerbated everything.”

Gross domestic product in sub-Saharan Africa will contract 1.6% this year, due to the economic devastation caused by the coronavirus, the International Monetary Fund forecast last month, revising its October prediction for a 3.6% expansion.

While banks are required to hold a certain amount of high-quality liquid assets such as government securities, regulators in Nigeria, Kenya and Ghana have berated lenders for not doing enough to support their economies in the past.

Regulatory Backlash

Profiting from the investments could result in a regulatory backlash, said Courage Martey, an Africa economist at Databank Group in Accra.

“If the potential sanctions or punishments are not likely to wipe out the potential benefits of holding risk-free Treasury debts, then the banks would most likely prefer to absorb the punishment in the hunt for high-yielding and safer treasuries than aggressive loan-book expansion.”

Nigeria’s central bank, which expects lenders to extend 65% of their deposits as credit, last month penalized those that failed to meet the target. Earlier this year, it limited transaction fees. And, in 2019, the regulator barred individuals and non-banking firms from buying short-term high-yielding bonds to stimulate lending for purposes other than market speculation.

Kenya in November scrapped a three-year rule that limited interest rates banks can charge. In 2014, Ghana boosted the rates it charges banks to discourage them from borrowing to buy local Treasury bills and profiting from the difference in the rates.

In South Africa, where banks have a loan-to-deposit ratio of more than 90%, the Treasury, regulators and banks are working on a 200 billion-rand loans guarantee program backed by the government to further stimulate lending.

Nedbank Group Ltd. Chief Executive Officer Mike Brown said last week that liquidity in South Africa is stable as lenders buy government securities to meet regulatory requirements. There has been a shortening in the duration of bonds being bought as banks position themselves for retail customers seeking to withdraw fixed deposits to cover their expenses, and businesses wanting to keep more cash on hand, he said.

Tighter Liquidity

The eight banks that buy bonds directly from the South African government bid for a record 30.8 billion rand ($1.7 billion) at an auction on Tuesday. South African 10-year bonds, which are highly liquid, yield 9.8%, compared with interest of 5.2% on a one-year cash deposit. The prime lending rate that banks charge their best customers is 7.74%.

Kenyan lenders face the risk of reduced deposits, said Faith Atiti, a senior economist at Nairobi-based NCBA Bank Kenya Ltd.

“I doubt banks can substantially increase their holdings in government securities,” she said. “Liquidity is likely to tighten as banks restructure loans.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.