A Wild Plan to Pull Gold Out of London Intrigues Maduro Officials

A Wild Plan to Get Gold Out of London Intrigues Maduro Officials

(Bloomberg) -- Versión en español

Charles Vincent is, for all intents and purposes, a nobody in the world of global finance.

Do a basic internet search for information on him or the Geneva-based firm -- Pipaud & Partners Sarl -- that he works for and almost nothing pops up. Swing by the address that Pipaud puts on its letterhead and there are no ostensible signs of its presence there.

And yet when Vincent showed up in Caracas in early August with a wild, almost fantastical, plan to free up some $1.5 billion worth of Venezuelan gold frozen in accounts in London, the nation’s central bankers not only received him but listened with great interest.

Vincent, a U.K. national, wowed them with a strategy he devised to work around sanctions that would otherwise forbid such a transaction, according to three people who heard the proposal or were briefed on it. One of the people said central bank officials are still contemplating if they will go ahead with it.

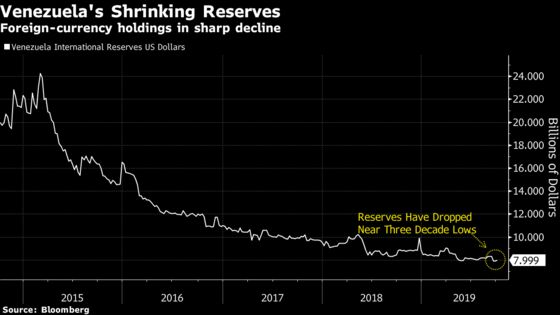

Whether they do or not, the fact that the meeting ever took place shows how determined, and desperate, Nicolas Maduro’s regime is to find ways to avoid U.S. sanctions that have choked off the flow of hard currency to the country and deepened the worst economic collapse in its history. Officials need the cash to fund crucial food imports and pay for the equipment and maintenance needed to keep the state oil company pumping at least some crude.

Self-described as an investment adviser, Pipaud acts as a commercial intermediary between businesses in Switzerland and abroad, according to registration documents in Geneva.

Vincent told Venezuelan policy makers that his firm could lobby English officials to free Venezuela’s gold and sell it to an Austrian bank for $1 billion, approximately a 30% discount to its current market value, according to a copy of his presentation seen by Bloomberg. It wasn’t explicit, but the documents seemed to suggest that Vincent would collect a portion of the gap between the gold’s commercial value and the amount that Venezuela would get.

Earlier this year, the Bank of England denied a request from the Maduro regime to withdraw its gold stored there, according to people familiar with the matter. The decision came after top U.S. officials lobbied their U.K. counterparts to help cut off Maduro from overseas assets, the people said.

Press officials for the Bank of England declined to comment. Yosendy Chirguita, a spokeswoman for Venezuela’s central bank, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Another scenario in Vincent’s five-page proposal called for Venezuela to use a state-owned metals refinery in the Austrian town of Graz to process the gold and then sell one ton a week to a Czech bank. In a separate idea, Vincent suggests that Venezuela, which has already defaulted on about $60 billion in overseas debt, could issue a $5 billion bond, underwritten by a bank in Singapore whose website indicates it specializes in offering services to waste disposal companies.

Sean Kane, counsel at Dechert LLP in Washington who previously worked at Treasury’s sanctions unit, said the proposals sounded far-fetched to him.

“It’s not at all unusual for sanctioned parties, such as the government of Venezuela, to look for more unorthodox fundraising mechanisms or counter-parties like this considering that any higher-profile bond trader or financial institution would have a lot to lose if sanctions are triggered,” he said.

In a sign of how seriously officials took Vincent’s ideas, they were willing to offer an answer when he asked how he’d get paid if the plan were executed, according to the people familiar with the meeting. They told him they could send him the money through Spain’s central bank, an institution that the Maduro regime has increasingly been trying to use to handle its international transactions.

A Bank of Spain official said Vincent’s firm Pipaud & Partners Sarl “doesn’t appear as a beneficiary or originator of any transaction in the account that the Venezuelan central bank has with the Bank of Spain.”

The Spanish central bank has said in the past that the amount of funds in Venezuela’s account is small and that there hasn’t been a significant change in activity in recent years. The transactions are limited mainly to transfers by multilateral organizations to get funds to their representatives in Venezuela, the Bank of Spain said.

Recent attempts by the Maduro government to raise capital, including Pipaud’s proposal, have caught the attention of officials at the U.S. Treasury Department, according to two people familiar with the matter. Officials have been privately pressuring banks they suspect could be party to such transactions to voluntarily comply with sanctions, the people said. A spokesman for the Treasury Department declined to comment on Pipaud or Vincent.

It wasn’t possible to reach Vincent for comment. Pipaud lists an address on Geneva’s left bank on its letterhead, but the company name appears nowhere on the cement-clad building, in its entryway or on the mailboxes in the foyer. A receptionist for a company that acts as a representative for Pipaud said it would deliver a message to Vincent but wouldn’t give out his email or phone number. A response never came.

In the documents presented to Venezuela, Vincent lists a home address in the exclusive French village of Eze, which dates from medieval times and overlooks the Cote d’Azur. Messages left at two phone numbers belonging to Eze residents with the last name of Vincent weren’t returned.

U.S. sanctions have largely isolated Venezuela from the global financial system, contributing to one of world’s most severe economic crises and forcing officials to use a patchwork of methods to move money around. The Venezuelan government has stepped up sales of gold to firms in places such as the United Arab Emirates and Turkey and has asked contractors to open accounts in obscure banks to receive payments.

Most recently, Venezuela’s central bank has run tests to determine whether it can hold cryptocurrencies in its reserves and use it to pay contractors abroad. The government has also studied the possibility of switching to a Russian-operated international payments messaging system as an alternative to the SWIFT system that most financial institutions use.

Vincent has been back to Caracas at least once since the Aug. 7 meeting to continue the efforts to sell his services, according to the people familiar with the matter. But for all the exotic scenarios under consideration in Caracas, for now the Maduro administration is left struggling to find the dollars it needs for the economy to operate.

--With assistance from Hugo Miller, David Goodman and Jeannette Neumann.

To contact the reporters on this story: Patricia Laya in Caracas at playa2@bloomberg.net;Ben Bartenstein in New York at bbartenstei3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Daniel Cancel at dcancel@bloomberg.net, ;David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Brendan Walsh

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.