A Leveraged Loan Collapses and Reveals Key Risk in Credit Market

Almost overnight, a $693 million loan Clover took to the market five years ago lost about a third of its value.

(Bloomberg) -- Operating out of a Chicago suburb, in a low-slung, red-brick building wedged between a Hyatt and a Radisson, Clover Technologies is in the mundane business of recycling everything from inkjet cartridges to mobile phones.

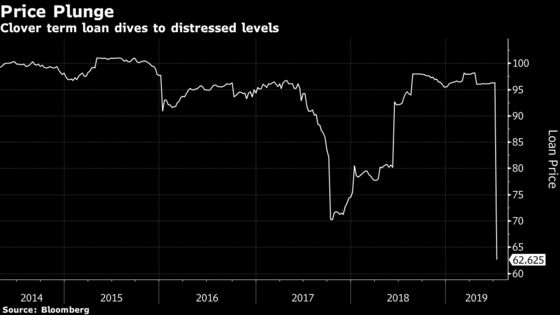

But in the past week it abruptly -- and alarmingly -- caught the attention of Wall Street. Almost overnight, a $693 million loan Clover took to the market five years ago lost about a third of its value. The startling nosedive stung even sophisticated investors, people who deal in the arcane business of trading corporate loans.

Clover’s loan isn’t especially large by Wall Street standards, yet its stark and swift decline set off fresh alarm bells -- bells that regulators have been sounding for months. It immediately became a real life example of the perils of investing these days in the $1.3 trillion market for leveraged loans, where a global chase for yield has allowed an explosion in borrowing and lax underwriting. In a market where trading can be thin -- and at a time when illiquidity is suddenly becoming a prominent concern in credit circles -- the episode shows how loans to highly leveraged companies can quickly implode when fortunes change.

When buyers “head for the exits at the same time, prices can drop fast and furiously” given the lack of liquidity, said Soren Reynertson of investment bank GLC Advisers & Co., which specializes in debt restructuring.

A representative for 4L Technologies Inc., Clover’s legal name, and its private equity owners, Golden Gate Capital, declined to comment.

Clover had been operating since 1996 when it was acquired by Golden Gate in 2010 for an undisclosed price. Golden Gate followed the usual path of private equity buyouts -- it piled debt on the underlying company to extract dividends.

Using the leveraged loan market as a wallet, the company took loans that funded dividend payments totaling at least $278 million -- $100 million in 2013 and $178 million in 2014. (Portions of the overall proceeds went to shareholders as well as to refinance the company’s existing debt and certain fees, according to a Moody’s report.) Clover also asked lenders for a further $100 million in 2014 to pay for an acquisition.

Those loans, as is typically done, were bought mostly by mutual funds and collateralized loan obligations, which bundle such leveraged debt into higher-rated securities that are pitched to more risk-averse investors. There’s been little trouble finding buyers for CLOs in recent years. With yields on high-grade bonds hovering near zero across much of the world, investors have been hungry for the juicy returns that these loans offer and, more and more, tend to overlook the lack of protection afforded.

Covenant Problems

Indeed, Clover’s deal, like many these days, was known as “covenant-lite.’’ It contained no provisions that required Clover to alert investors to signs of trouble after undergoing financial tests every quarter. That meant that investors were left with little leverage over the company. Jessica Reiss, head of leveraged loan research at Covenant Review, describes the growing number of weak credit agreements as “death by a thousand paper cuts.”

But Clover’s substantial debt left little room for error, and soon after the company began struggling. In 2014, S&P Global Ratings lowered the company’s outlook to negative and three years later Moody’s Investors Service and S&P downgraded its rating. Still, with the exception of a sell-off two years ago, the loan largely held its value in the secondary market.

Until July 9. Clover disclosed that day it had lost two key customers and hired advisers to study its options. The price of its loan quickly plummeted from 97 cents to around 65 cents, which put it in the distressed category.

Two days later, Moody’s downgraded the company a notch to Caa3. It cited its “aggressive financial policies, evidenced by its private equity ownership and history of shareholder distributions and large debt-funded acquisitions.’’

Distressed Loans

The downgrade accelerated the fall by creating a bevy of sellers. CLOs and mutual funds, among the biggest holders, were likely forced to dump Clover debt because they are limited in how much they can own in distressed loans.

Investors also bore all the losses because the financing was structured as a single loan -- no other loans or high-yield bonds were used. In other troubled deals, any unsecured debt would take the brunt of the losses first, cushioning the blow. The use of these loan-only capital structures is rising, showing up in about 60% of buyouts, a sign of just how pliant investors have become.

Moody’s now predicts a higher likelihood Clover will default on its debt obligations. The ratings agency cites concerns over long-term viability of the business and “unexpected” operational developments. Its debt is just over 6 times its earnings, a level that typically raises lender concerns about the company’s ability to meet its financial obligations. Another warning sign came in May when the company pulled a seemingly attractive refinancing plan that offered a high yield of nearly 9% with a short, three-year maturity.

Investors may recall similar blowups in the credit market. American Tire Distributors’ bonds and loans plunged into distress less than a month after it announced the loss of two key suppliers, Goodyear and Bridgestone. ATM-maker Diebold Nixdorf Inc. also saw its bonds fall to almost half their face value after it posted an unexpected second quarter loss.

“Highly levered companies are even more sensitive to reductions in revenue,’’ said Reynertson. “Cash flows can evaporate overnight.”

--With assistance from Sally Bakewell.

To contact the reporters on this story: Katherine Doherty in New York at kdoherty23@bloomberg.net;Lisa Lee in New York at llee299@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rick Green at rgreen18@bloomberg.net, ;David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Larry Reibstein, Natalie Harrison

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.