A Japan-U.S. Pact Looks Like the Opposite of Free Trade

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Remember last month, when an agreement between the U.S. and Mexico left the world thinking we were on the brink of a radical rewriting of the North American Free Trade Agreement?

Things haven’t quite gone to plan. With a touted Sept. 30 deadline for an accord just days away, President Donald Trump went on a tirade Wednesday about his dislike of his Canadian interlocutors and turned down a meeting with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

That’s a decent framework for thinking about the prospects of a mooted Japan-U.S. trade deal announced by the White House within hours of Trump’s trash-talking.

Look, for instance, at the key areas highlighted in the joint announcement by the governments. The U.S. wants to gain “market access outcomes in the motor-vehicle sector” to increase jobs in its rust belt, while Japan says it won’t go any further in opening agricultural trade than it proposed in previous agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

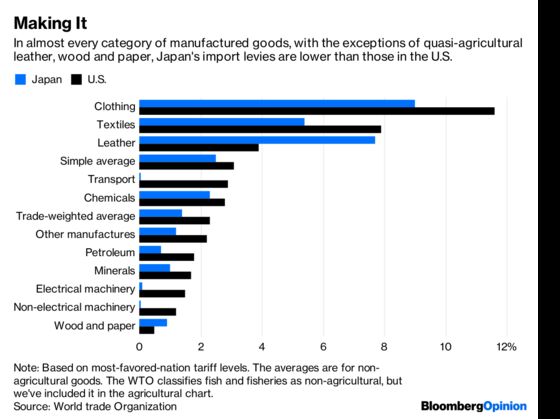

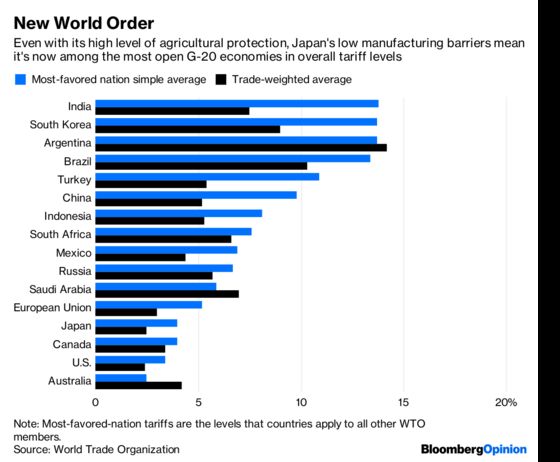

Examine the structure of import levies by the two nations and the problem becomes obvious. For all that Trump likes to think of Japan as the mercantilist nation it was when manufacturing exports fueled its postwar ascent, these days the U.S. is the more protectionist nation on that front.

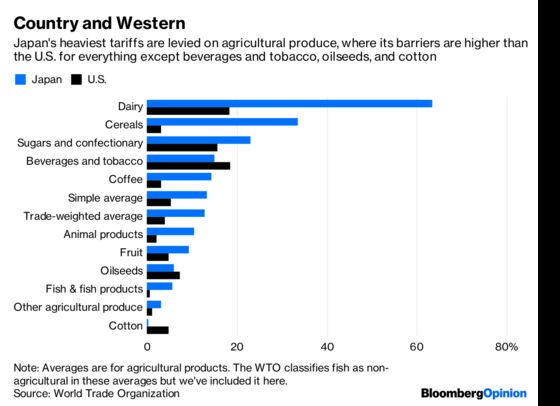

Tariffs are lower in Japan than in the U.S. for every category of manufactured goods except leather. On transport equipment, they’re set to zero: Japan removed its last levies on automotive imports as far back as 1978, while the U.S. still charges 2.5 percent on cars and 25 percent on light trucks. It’s in agricultural produce that the Asian country sticks the barriers up – imposts can run as high as 96 percent.

The issue of market access for U.S. cars in Japan has cropped up every decade since the 1970s, but it’s usually generated more heat than light. Japan’s carmakers found their way into the U.S. because consumers there wanted small, efficient, and reliable cars, whereas a Japanese market made up of hybrids, small cars and people-carriers sees little use for the gas-guzzling SUVs on which Ford Motor Co. will now be almost entirely focused.

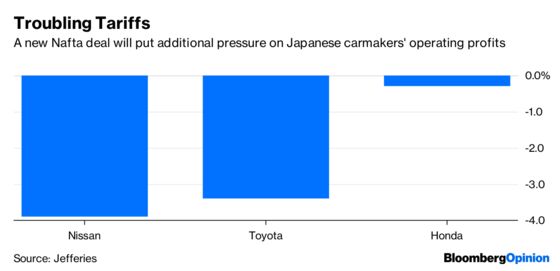

For the likes of Toyota Motor Corp. and Honda Motor Co., which count the U.S. among their largest markets and whose vehicles are among America’s top-selling models, talk of a deal will hardly move the needle. The U.S. auto market is plateauing. While numbers for Detroit’s big three are ticking up on sales of tariff-protected trucks and incentive discounts, foreign carmakers are pulling back, further reducing consumer choice. The Japanese are pivoting to China, for instance, where prospects for electric cars and broader growth are better.

That illustrates the wrong-headedness of the current proposal. The criminal Willie Sutton famously explained that he used to rob banks “because that’s where the money is.” In the same vein, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, from which Trump withdrew during his first week in office, sought to cut Japanese agricultural tariffs and U.S. barriers on manufactured goods because that’s where the restrictions are.

Every U.S. administration has tried a new trade strategy with Japan in the hopes that something will stick. The Reagan government came up with a sector-specific effort to boost exports in pharmaceuticals, telecom and autos. That didn’t help increase exports for the auto sector. Meanwhile, the George H. W. Bush administration targeted non-tariff barriers like Japan’s land-use policies and the keiretsu business model – again, not much has changed. Bill Clinton formulated a bilateral agreement with Japan that brought together bits of the Bush and Reagan frameworks. None has shifted the balance significantly, and there aren't many more American cars on the streets of Japan.

As a result, a deal that seeks to promote U.S. manufacturing without doing too much pain to Japanese farming looks like a non-starter.

Japan has shown a clear preference for a revised version of the TPP over any bilateral deal, either without but preferably with the U.S. as a member. Its parliament in June passed key bills needed to formalize the 11-nation version of the deal, so it only needs other nations to ratify for the TPP-minus-U.S. agreement to become a reality.

Faced with a still-powerful farm lobby, it’s hard to imagine Prime Minister Shinzo Abe agreeing to reduce agricultural barriers to the same extent as the TPP without the U.S. making concessions at least as dramatic on manufacturing. Perhaps a shorter phase-in for tariff reductions than the absurd 25-year period agreed on in the TPP would be possible. But it’s hard to see the Trump administration accepting a deal that would be seen as selling out voters in the Midwestern rust belt, with midterm elections just weeks away.

Every trade agreement is a matter of give and take. In this negotiation, each nation would like to raise the prospect that they’ll be able to take a little away from the other side’s barriers to trade. Without some give, though, it’s hard to see any agreement hanging together.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Paul Sillitoe at psillitoe@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.