A Hard Rain, Dead Chickens, Lost Jobs: Brazil's Sad Alumina Saga

A Hard Rain, Dead Chickens, Lost Jobs: Brazil's Sad Alumina Saga

(Bloomberg) -- Norsk Hydro ASA’s decision to close its alumina refinery in Brazil was preceded by a hard rain, a dam spill, and a debate about dead chickens and cows.

Now, the concern is as much about lost jobs as it is about the plant’s wastewater. An estimated 4,700 workers face unemployment after the Norwegian company said needless court injunctions are making it impossible to keep operating the world’s largest refinery for alumina, a key ingredient in aluminum, along with two associated facilities.

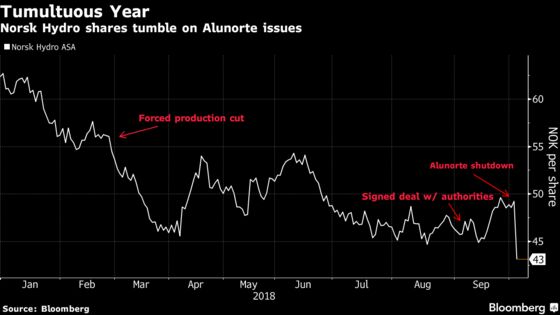

The announced closure -- the company declined to say when the plant may reopen -- caused Hydro’s shares to plunge and global aluminum prices to surge. Hydro blamed a specific embargo that prevents it from using the newer of two wastewater ponds at the site, after prosecutors said a February spill contaminated the adjoining Para river and local water supplies.

Hydro announced the shutdown Wednesday, just days after prosecutors said it should take at least a year before the Alunorte refinery could resume full production. In a conference call with analysts, Hydro Chief Executive Officer Svein Richard Brandtzaeg said it was "impossible to say" when the court that ordered the plant to halve its operations would allow it to reopen at full production.

Creating Urgency

"But it’s clear,” he said, "that this situation is creating some urgency in Brazil. It is a quite dramatic situation for Hydro, but also for Para state. There have been several meetings arranged already and they are very important meetings."

Leonam Gondim da Cruz Jr., a Para state judge who rejected a Hydro appeal to overturn the injunction forcing the cut in production, called the shutdown announcement “a bluff" in a telephone interview.

"They know that they have a lot of people employed in Barcarena," the judge said on Wednesday. "The idea is to intimidate and pressure the authorities into retreating so that they can return to normal activity.”

Meanwhile, in a posting on the city’s official website, Barcarena Mayor Antonio Carlos Vilaca called for “an immediate response to the problem to guarantee the employment of our workers." The shutdown, he wrote, "would cause significant losses to the city, affecting direct and indirect jobs."

The legal dispute has already been a drag on local businesses, said Reginaldo Garcia, who runs a beach-side restaurant in Barcarena. “Hydro closes, and it’ll be the end of everything around here," he said in an April interview, adding that he had less people coming to the restaurant because of TV coverage on the spill.

"They don’t want to eat our fish, thinking it came from the river,” he said, “even though we bought it at a supermarket far from here."

Barcarena, with a population of roughly 100,000, sits next to the plant on the shores of the Para, a flood-prone river that combines two others before rushing out to sea. When heavy rains hit, residents are used to seeing their property under water.

What Patricia Neves, who sells eggs to support her family, wasn’t used to seeing were dozens of dead chickens after the February flooding. They died, she believed, from drinking dirty floodwater. While she blamed the spill, she admitted the water may have also been contaminated by a nearby mass grave containing an unknown number of dead cows, buried there after thousands drowned in huge barge accident in the nearby river.

Meanwhile, the company has argued in court and with prosecutors that no toxic materials leaked in February, countering statements by researchers who have said they discovered traces of heavy metals in water supplies.

That’s the problem in Barcarena, deciphering one clear reason for contaminated water may be next to impossible.

The community has the worst sewage treatment of any city in Brazil with more than 100,000 inhabitants, according to a federal study released in mid-July. The report also said that local streams and rivers may show toxic levels due to chronic issues related to the industrial district where Alunorte is located, along with other businesses involved in mineral extraction.

Hydro’s Alunorte refinery had enjoyed several years of robust production before the alleged spill occurred. Since then, local newspapers have sometimes painted the company as a villain and a local court quickly ordered Alunorte to halve its production until it could adequately explain what happened, and insure it wouldn’t happen again.

Hydro was initially optimistic the output reduction would be quickly remedied, perhaps because a similar event had occurred in 2009 and the company came through it with little punishment. Now, it’s a different story, and the metals world is taking note.

"Alumina is an 80 million ton market," said Oliver Nugent, a commodities strategist at ING Bank NV. "The indexes survey less than a million tons a year. So that’s 80 million tons priced on just a tiny amount of cargo."

--With assistance from Joe Deaux.

To contact the reporter on this story: R.T. Watson in Rio de Janeiro at rwatson71@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Luzi Ann Javier at ljavier@bloomberg.net, Reg Gale

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.