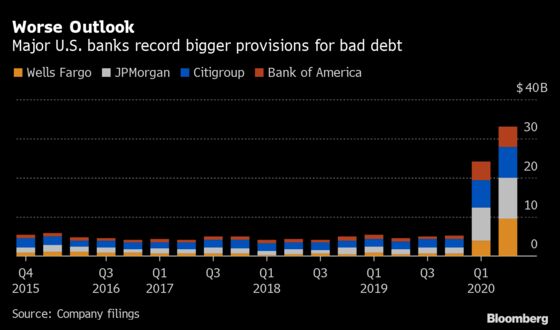

A $35 Billion Bite From U.S. Bank Profits May Only Be the Start

A $35 Billion Bite From U.S. Bank Profits May Only Be the Start

(Bloomberg) -- The six giant U.S. banks that just cut $35 billion from their profits to brace for a tsunami of souring loans also offered this confession: They don’t really know how bad it’s about to get.

Data that normally hints at pending losses on loans isn’t obeying the financial world’s usual laws of physics amid a slew of government programs temporarily propping up consumers and businesses. The percentage of loans falling into delinquency unexpectedly fell this year even as millions of Americans lost their jobs. People who arranged to defer payments on credit cards and mortgages dutifully sent checks anyway.

It’s an unprecedented situation, forcing bank leaders to make big assumptions about how the pandemic and the government’s response will play out, and what that means for the economy. To adjust its reserves, Citigroup Inc. imagined unemployment might improve modestly to about 10% by year-end. To show it can handle tougher times, JPMorgan Chase & Co. ran projections with it surpassing 20%.

But then, as bank leaders disclosed their massive provisions in second-quarter results this week, they took turns urging investors not to put too much stock in those numbers.

“We are in a completely unpredictable environment for which there are no models, no cycles to point to,” Citigroup Chief Executive Officer Michael Corbat told analysts.

“It’s just very peculiar times,” said JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon. “In the normal recession, unemployment goes up, delinquencies go up, charges go up, home prices go down. None of that’s true here.” Instead, he said, “savings are up, incomes are up, home prices are up.”

For example, the serious delinquency rate on consumer debt -- mortgages, credit cards, car loans and the like -- fell by half between the end of March and the end of June to 0.7%, according to credit bureau Equifax.

Bank of America Corp. added to the ambiguity Thursday, when the lender’s provision came in at roughly half the level of its closest rivals. Executives defended the discrepancy, saying the company has less exposure to the hardest hit industries and has focused on wealthier consumers in recent years. Chief Financial Officer Paul Donofrio said the firm has been going loan-by-loan to analyze its risk.

“Right now we are seeing nothing that is consistent with an 11% unemployment rate,” CEO Brian Moynihan said on a call with analysts.

To the industry’s credit, the warnings this time contrast with the situation heading into the 2008 financial crisis, when banks’ initial writedowns on bad mortgages often came with assurances the worst was over. That proved to be cataclysmically wrong.

When Citigroup announced $5.9 billion of credit and trading losses on Oct. 1, 2007, then-CEO Charles Prince predicted earnings would return to “normal” in that year’s fourth quarter. The bank went on to lose $9.8 billion in the last three months of that year and far more in 2008.

The arc of borrower defaults in that recession -- when unemployment topped 10% -- could prove instructive in projecting the impact this time. For example, the industry’s net charge-off rate doubled in 2008, and then doubled again the following year before peaking at 3.12% in the first quarter of 2010, federal data show.

Banks collectively entered this year’s second quarter with loss reserves equivalent to 1.76% of loan balances. After its massive provision this month, JPMorgan’s reserves are now around 3% of total loans. If the entire U.S. banking industry were to get to that level, it would mean more than $130 billion in provisions for this quarter alone.

Compounding the uncertainty this time is the unpredictability of the pandemic. Americans, for example, are failing to contain infections by taking steps that have worked in other nations. A surge in new cases this month now threatens to further impair commerce at a time when the government had planned to taper support for consumers and businesses.

A $600 weekly unemployment benefit for millions of Americans is set to expire at the end of July. A $669 billion financing program for millions of small businesses is slated to end early next month. A Goldman Sachs Group Inc. survey of those borrowers found that 84% expect to exhaust their funding by the first week of August, and only 16% are confident they can keep paying staff without more support. It’s unclear whether Congress will agree to extensions.

But even if the government curtails aid, it may take at least several months for banks get a sense of how many consumers and businesses will fail to repay debts. “I mean, first, we have to start seeing delinquencies,” JPMorgan CFO Jennifer Piepszak told analysts when pressed to estimate timing for charge-offs.

In the meantime, provisions require guesswork.

“In all honestly there’s a fair amount of judgment that comes into play,” U.S. Bancorp CFO Terry Dolan said. “It’s probably the fourth quarter and first quarters of next year where we will start to truly see what the implications are from a consumer standpoint.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.