A 24-Year-Old Is Suing His Pension Fund for Not Being Green Enough

A 24-Year-Old Is Suing Pension Fund for Not Being Green Enough

(Bloomberg) -- Mark McVeigh, a 24-year-old environmental scientist from Australia, won’t be able to access his retirement savings until 2055. But, concerned about what the world may look like then, he’s taking action now, suing his A$57 billion ($39 billion) pension fund for not adequately disclosing or assessing the impact of climate change on its investments.

The Federal Court battle is shaping up to be a unique test case. Are pension funds in breach of their fiduciary duties by failing to mitigate the financial ravages of a warmer planet?

Before launching the legal action, McVeigh asked Retail Employees Superannuation Trust, or Rest, how it was ensuring his savings were future proofed against rising world temperatures. Its response didn’t satisfy him and he ended up engaging specialist climate change law firm, Equity Generation Lawyers.

“I see climate change as a huge risk that dwarfs a lot of other things -- it’s such a big physical impact on the planet, and the economy,” McVeigh said in a phone interview from Brisbane, where he works as an ecologist for a local government. He said other people had contacted him on learning of the case and also wanted such information from their funds.

Rest says climate change is just one of a variety of factors it must consider when investing the savings of its around 2 million members, which include grocery-store clerks and shop keepers, according to court filings.

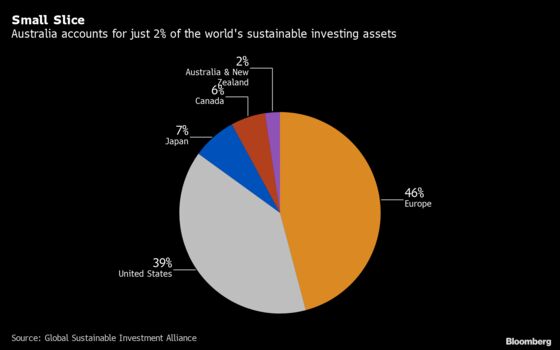

Australia’s pension industry -- home to the world’s fourth-largest retirement-savings pool at A$2.9 trillion -- is watching the case closely, particularly because many funds must also meet legislated minimum return targets. While investing in renewable-energy projects and pressuring miners to be better corporate citizens is all well and good, this requirement makes it more complicated than simply dumping fossil-fuel emitters from a portfolio.

Interests of Members

“Looking after the best financial interests of our members requires us to be conscious of the risks, but not exclude a whole segment of the economy that’s going to be very meaningful for a period of time,” said Ian Patrick, chief investment officer at Sunsuper Pty, which manages A$70 billion. “Right now, the interests of our members -- the sole purpose of super -- is what wins out.”

Australia’s mandatory retirement savings system, known as superannuation, is meant to relieve pressure on the public purse as the nation’s population ages, lives longer and requires a steady income stream to survive. Much of the industry must strive to return 3.5% above inflation over a decade.

But returns aside, members like McVeigh want to see their savings last as long as possible in an uncertain environment, with polls showing increasing public concern about climate change.

“Investors may not be sufficiently factoring in the impact of climate-change risk on future economic growth,” said Jennifer Wu, global head of sustainable investing at JPMorgan Asset Management.

Firms are beginning to act, with a study by State Street Global Advisors released Wednesday finding that fiduciary duty is one of the main ‘push factors’ for financial institutions to adopt environmental, social and governance principles.

Sunsuper, AustralianSuper Pty, Construction & Building Unions Superannuation, Health Employees Superannuation Trust Australia and others have employed responsible investment teams to integrate ESG factors into their portfolios. They’ve joined global investor initiatives such as the United Nations-backed Principles for Responsible Investment and they’ve used their sizable holdings in companies like BHP Group Ltd. and Glencore Plc to agitate for change.

Conversations around engagement versus divestment are frequent when five or so years ago, they pretty much didn’t exist.

Mary Delahunty, who as head of impact at HESTA is responsible for improving the A$50 billion fund’s responsible investment practices, says selling out isn’t always a prudent option.

“As soon as you remove capital, they don’t have to have a conversation with you anymore,” she said.

| To read more on pension funds and climate change: |

|---|

| Passive No More, Australia Pension Giants Flex Muscle on ESG |

| $94 Billion Fund Plans to Cut Australia Carbon Footprint by 10% |

| First State Super Supports BHP Shareholder Resolution on Climate |

| AllianceBernstein Wins A$170 Million Low-Carbon Equities Mandate |

| Sunsuper Awards Green Bond Mandate to Affirmative Investment |

Debt is another way pension funds are trying to manage climate risk in their portfolios.

Sunsuper has written loans to gas companies in the Permian Basin in the U.S., rather than taking equity stakes and running the risk of being left with a stranded asset. Those loans deliver double-digit returns over periods of up to 10 years while the world shifts to a cleaner energy mix, Patrick said.

“It’s why we prefer debt and why we think about the tenor of that debt quite deeply,” Patrick said. “Relative to holding long-term equity in an energy asset, that addresses the risk quite substantially.”

While activism is rising and investors and banks are shying away from financing environmentally damaging projects, the Australian government is going the other way. Prime Minister Scott Morrison, a staunch supporter of the coal-mining industry, is considering new laws to prevent activists like environmental lobby group Market Forces from stymieing commercial decisions and threatening economic growth.

The McVeigh case, which is back in court Nov. 22 for a preliminary hearing, has also gained international attention, even though climate change litigation isn’t new (oil companies in the U.S., for example, have been sued to recover the cost of rebuilding to protect against rising sea levels).

As well as improving its environmental disclosures, Rest recently appointed a responsible investment manager and in June, took control of a wind farm in Western Australia from a UBS Group AG unit.

The fund also said it had sought to meet with McVeigh to discuss his concerns. “Specific climate-related issues which we engage with our investment managers on include carbon foot printing, stranded assets, climate-related scenario analysis and exposure to lower carbon assets,” a spokesperson said in an emailed statement.

Michael Gerrard, a professor of environmental, climate change and energy law at Columbia University, said that “success in litigation breeds imitation, so if McVeigh wins, people will take a close look.”

“People are so desperate at the failure of governments to act adequately on climate change that they’re looking for litigation targets.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Matthew Burgess in Melbourne at mburgess46@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Edward Johnson at ejohnson28@bloomberg.net, Katrina Nicholas

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.