Tariffs to Talks: The U.S.-China Trade War, Explained

The trade war roiling the global economy is being fought not trench by trench but product by product.

(Bloomberg) -- What started in 2018 with U.S. levies on imported washing machines and solar panels to protect domestic producers escalated into a cycle of tariffs, talks, threats and truces that rocked financial markets. Behind all the sparring between the U.S. and China -- one an incumbent superpower, the other a rising one -- over tariff levels and targeted product lists are broader and more formidable issues such as market access, intellectual property, national security, the proper role of government in the economy and a deepening competition for advantage in emerging technologies.

1. Why are we in a trade war?

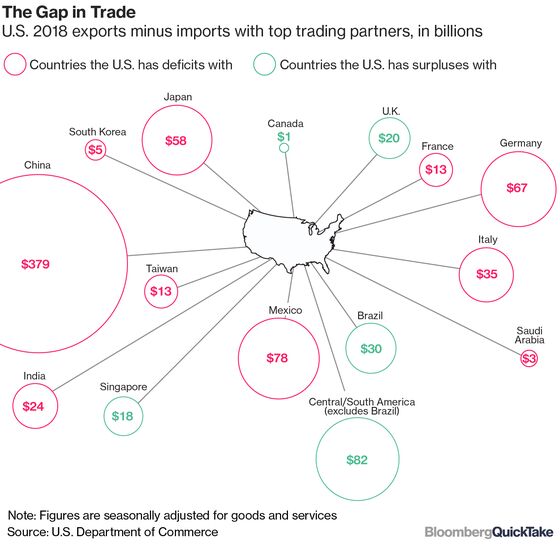

U.S. President Donald Trump, who calls himself “Tariff Man,” says China and other trading partners have long taken advantage of the U.S., an argument that enjoys broad support in Washington across party lines. He points to the trade deficit (the difference between imports and exports) as evidence of a hollowing out of U.S. manufacturing and the loss of American might. Over more than year, he ratcheted up tariffs, which are a tax on imports, while encouraging U.S. companies hurt by them to move production — and jobs — back home.

2. Who are Trump’s targets?

Mainly China, which accounts for the bulk of the deficit. But Trump also pulled the U.S. out of a proposed trade deal with Japan and 10 other Asia-Pacific countries, calling it unfair for U.S. workers, and started talking directly with Japan instead. He has threatened 25% tariffs on millions of imported cars and car parts from Europe and Japan, and insisted on renegotiating (and renaming) the 1994 pact with Canada and Mexico known as Nafta. Trump has also threatened to impose tariffs as retaliation against France for its new digital tax on technology companies.

3. What’s special about China?

China’s admission into the World Trade Organization in 2001, under rules that granted it concessions as a developing country, greatly accelerated its integration with global markets and supply chains. Studies have shown that Chinese exports led to lower prices for U.S. consumers — and helped lift millions of Chinese out of poverty. The country’s ascent also resulted in the loss of millions of U.S. factory jobs. China’s power — especially its technological prowess — is now at a point where it risks eroding American military and economic advantages. China insists it plays by global trade rules, and it sees the U.S. as seeking to contain its rise. It is accelerating the development of its own high-technology industry to be less dependent on the U.S.

4. How did the war escalate?

Trump hit steel and aluminum imports from several countries on national security grounds, arguing that a weakened U.S. industry would be less able to build weaponry in a crisis. Tariffs on goods specifically from China started in July 2018. China responded in kind. Before the year ended a truce was called and a deal seemed to be in the offing. But in May 2019, Trump started raising tariffs on a scale not seen in decades, provoking further retaliation. Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed in June to restart talks. Then Trump, claiming China had failed to keep a promise to buy more from American farmers, threatened a 10% tariff on all remaining imports from China, including clothes, shoes and electronics. Some took effect on Sept. 1. Others were to be introduced Dec. 15, but they were headed off by a partial deal that was also to roll back some other U.S. tariffs. Trump has said he wants to keep tariffs in place until he’s sure China is complying with any deal — which means they could be around for years.

5. Who pays the tariffs?

A middleman — the U.S. importer of record — pays the tariff when the product lands in the country. The importer might absorb the cost or pass it along to a wholesaler, who might pass it to a retailer, who might raise the price for consumers. In those cases, Americans pay. Or the Chinese producer might cut factory prices to make up for the tariffs, or shift production outside China to avoid them. In such cases, the economic pain would be felt in China. A United Nations report released Nov. 5 concluded that U.S. consumers were bearing the brunt, but that Chinese companies were starting to absorb some of the costs as well.

6. Is Trump’s strategy working?

The U.S. trade deficit increased to a 10-year high of $621 billion in 2018, and the trend was continuing in 2019. Economists say the trade war actually helped to widen the gap by contributing to an economic slowdown in China and Europe. Meanwhile, American farmers have lost markets and income as China and other trading partners raised tariffs in retaliation. Trump is holding tight to his view that the trade war is helping the U.S. economy. Although some economists have warned of a recession risk, a record expansion continues to defy doomsayers and the unemployment rate is at its lowest in half a century.

7. What about in China?

The UN report found that exports of Chinese goods hit by the tariffs dropped 25% in the first half of 2019, for a loss of $35 billion. That’s consistent with an earlier analysis by Bloomberg Economics that showed U.S. imports of Chinese goods hit by tariffs in 2018 were down 26% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2019. In the same period, Taiwan and South Korea saw sales of electronics components accelerate, and Vietnam saw the same with furniture -— a sign that tariffs have accelerated the shift of low-end manufacturing out of China. Giant Manufacturing Co., the world’s biggest bicycle maker, started moving production of U.S.-bound orders out of its China facilities to its home base in Taiwan as soon as it heard Trump threaten tariff action in September. In another warning sign for China, factory prices have been falling, reflecting a weakening domestic economy.

8. Who else is vulnerable?

U.S. companies including Walmart Inc. and Nike Inc. have warned of higher prices. Apple Inc. faced hits in both directions, since its popular iPhone is assembled in China in part with components made in the U.S. Dell Technologies, HP, Intel and Microsoft have all opposed Trump’s proposed tariffs on laptop computers and tablets, arguing they would increase prices for consumers and hurt small businesses. Bloomberg Economics estimated in June that the cost of the U.S.-China trade war could reach $1.2 trillion by 2021, with the impact spread across the Asian supply chain. That estimate is based on 25% tariffs on all U.S.-China trade and a 10% drop in stock markets. (It doesn’t count Brexit or threatened U.S. tariffs on imported cars.) Some economists even predicted a global recession, although the outlook seemed to be brightening by the end of the year.

The Reference Shelf

- This video chronicles Trump’s aggressive policies and unpredictable behavior.

- QuickTake explainers on China’s slowdown, forced technology transfers and the intellectual-property dispute.

- Bloomberg Opinion columnist David Fickling warns China risks overplaying its hand, Mihir Sharma defends the global trading system, and Robert Burgess looks at what trade optimism means for markets.

- From sushi to ski gloves, the U.S. needs China more than you think.

- The Center for Strategic and International Studies looks at a way to get from truce to lasting deal.

To contact the reporter on this story: Enda Curran in Hong Kong at ecurran8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, ;Jeffrey Black at jblack25@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner, Leah Harrison Singer

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.