Boeing Max Grounding Endangers Cash Machine Adored by Wall Street

For nearly two decades, Boeing Co.’s mass-produced 737 jetliner has doubled as its cash machine.

(Bloomberg) -- For nearly two decades, Boeing Co.’s mass-produced 737 jetliner has doubled as its cash machine.

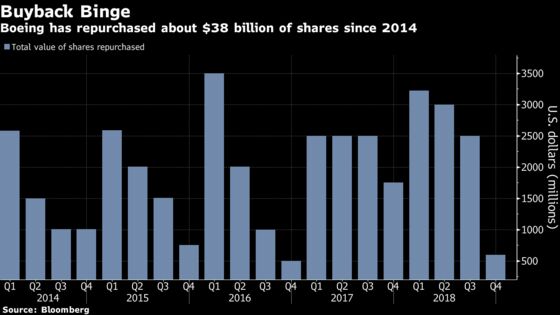

The single-aisle plane, a favorite of budget carriers, bankrolled a decade of losses for the 787 Dreamliner and a more recent stock-buyback spree of $38 billion -- an amount equivalent to Ford Motor Co.’s market value. The newest version of the aircraft, the Max, was poised to become Boeing’s largest source of revenue and profit this year.

But since regulators grounded the best-selling 737 model indefinitely following two deadly crashes, the largest U.S. industrial company is in an unfamiliar position: conserving cash. That puts Boeing’s share repurchases at risk while threatening financial repercussions into 2020 and beyond if the 737 brand proves to be irreparably damaged.

Given the strain on its production resources, shoveling billions to investors “wouldn’t sit well,” said Nick Cunningham, managing partner with London-based Agency Partners. “The logical thing is to preserve cash because you might need it.”

A Boeing spokesman declined to comment on the cash plans, citing a quiet period ahead of the company’s first-quarter earnings release scheduled for Wednesday. The report will provide the first glimpse of the financial fallout from the March 10 crash of an Ethiopian Airlines jet, the second deadly Max accident in a five-month span. Combined, the two disasters killed 346 people.

$10 Billion Drag

After the earnings report, Boeing management’s discussion with analysts is likely to be “one of the most listened-to calls in industrial stock history,” Carter Copeland of Melius Research said in a note to clients last week. While the planemaker is widely expected to pull its 2019 guidance, little else is certain, he said. That has left investors “desperate for a bounding of outcomes” for this year and beyond.

All told, the Max could be a $10 billion drag on Boeing’s cash this year, predicted Barclays Plc analyst David Strauss in an April 15 report. The shares fell less than 1 percent to $374.02 at the close in New York on Tuesday. Boeing has dropped 11 percent since last month’s tragedy, the biggest share drop on the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The decline wiped out more than $27 billion in market value.

Still, the prospect of an eventual rebound has helped limit losses for investors. Strauss sees Boeing gaining a $5 billion tailwind next year as deliveries and payments flow for the 300 or so aircraft he estimates the company will have parked.

“I think the most likely scenario is this airplane is flying again by the end of the third quarter, and Boeing goes hammer and tongs to get the deliveries out the door by the end of the year,” said George Ferguson, analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence. “If that’s the case and you’re an investor, the story is still intact.”

Regulators, Prosecutors

Still, there’s the risk that investors will lose patience if regulators are slow to clear the 737 Max to fly. Boeing has redesigned software linked to the two crashes to prevent it from erroneously misfiring and overwhelming pilots. The changes face a rigorous review from a technical panel, convened by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, with members from eight countries and the European Union.

Meanwhile, U.S. prosecutors and congressional investigators are exploring how the flaws in the system, known as MCAS, escaped notice. That leaves open the possibility of additional damaging revelations.

“This whole episode shows the danger of relying on just tons of increasing cash flow to generate shareholder returns,” said aviation consultant Richard Aboulafia. “To their credit, they’re also funding new product development with the 777X, which is more than Airbus can say right now,” he said of Boeing’s European rival.

Inventory Jump

Free cash flow, which has guided the money Boeing returns to investors and is tied to executive compensation, will probably be dented until the Max grounding is lifted and commercial flights resume. For now, Boeing must absorb manufacturing costs for 737 jets it isn’t yet able to sign over to customers. About 225 of the undelivered aircraft could be in storage by the end of June, according to analyst Ken Herbert of Canaccord Genuity.

Boeing’s ratio of inventory to assets had already ballooned to a record 51 percent as of late 2018, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The measure of overstocking is the fifth highest among members of the S&P 500 Index, reflecting dozens of KC-46 tankers parked as Boeing awaited Pentagon sign-off and 737s that lacked engines at year-end.

While Boeing has temporarily slowed its 737 final assembly line by 19 percent to build 42 planes a month, the company is also picking up the bill as Spirit AeroSystems Holdings Inc. and other suppliers continue at the previous pace of 52 a month. The strategy will add to Boeing’s inventory costs as Spirit stashes extra 737 frames near its factory complex in Wichita, Kansas.

Keeping the supply chain running hot will make it easier for Boeing to quickly ramp up output as the crisis abates. It also helps insulate smaller suppliers, which are already under pressure from discounts that Boeing has demanded this decade.

“They’ve been sticking it to suppliers since 2011, now they need suppliers more than ever,” said Kevin Michaels, managing director at AeroDynamic Advisory. “There’s less working capital in the supply chain to be able to deal with this kind of crisis.”

Damaged Trust

Looming over the short-term financial impact of the Max’s grounding is a bigger question about the plane’s market appeal after the two accidents damaged public trust in Chicago-based Boeing.

Executives have vowed to make the plane safer than ever as they work to rebuild consumer confidence. And defecting might be tricky for airlines, with Airbus SE grappling with factory delays for its A320neo jets and a full order book through 2023.

Other aircraft associated with tragedy, such as McDonnell Douglas Corp.’s DC-10, continued to sell for years. But they did so on a smaller scale. And Boeing had already been losing market share to Airbus, reversing the superior pricing and margins it had enjoyed with earlier versions of the 737, said Cunningham of Agency Partners.

Such factors make a good case for accelerating an all-new replacement for the jet, a transition that hadn’t been expected until late next decade, Cunningham said.

That’s another question mark for investors because committing to an expensive aircraft-development program would entail shifting from Boeing’s current strategy of harvesting profits from the 737 and ladling cash into shareholders’ pockets.

“From an investment standpoint, that’s a huge risk,” Cunningham said. “Instead of selling this nice old airplane you’ve been selling for 50 years at very high margins, you’ve got to make a new one.”

--With assistance from Brandon Kochkodin.

To contact the reporter on this story: Julie Johnsson in Chicago at jjohnsson@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Case at bcase4@bloomberg.net, Susan Warren

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.