Malaria Vaccine Took 30 Years. It’s Still a Work in Progress

After more than three decades of work and almost $1 billion of investment, GSK is ready to deploy a vaccine for malaria.

(Bloomberg) -- After more than three decades of work and almost $1 billion of investment, GlaxoSmithKline Plc and its partners are ready to deploy a vaccine for malaria, the mosquito-borne disease that kills almost half a million people each year.

The vaccine, developed with the non-profit organization PATH, comes at a critical time and marks a milestone in the battle against the parasite that causes malaria. But the injection is a pioneer, not a panacea: it prevented only about four in 10 malaria cases among children who received four doses in a large study.

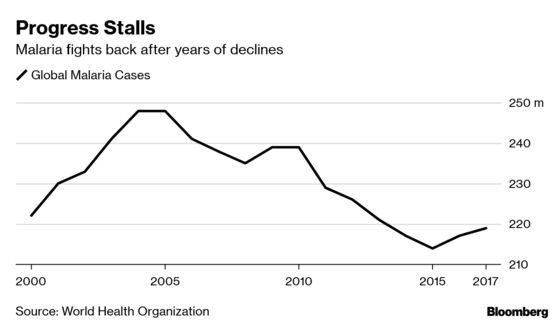

A pilot program is scheduled to begin this month in Africa to size up the product, which has the potential to save tens of thousands of children’s lives, according to the World Health Organization. After declining for many years, malaria is staging a comeback. The ultimate impact may depend on securing more international funds at a time when countries are increasingly turning inward.

“Mobilizing funding for these major endeavors which do not have a commercial opportunity has been a challenge, and will be an even bigger challenge in the future,” said Thomas Breuer, chief medical officer of Glaxo’s vaccines unit.

U.K. drugmaker Glaxo, which estimates it’s spending more than $700 million on the project, would like to “hand over the funding baton to others,” according to Breuer. The company said it’s talking with partners and other groups about financing and rolling out the vaccine after the pilots.

Several hundred million dollars more, for instance, will be needed for a manufacturing plant to expand use, according to a December report published in the science journal Nature.

The vaccine brings a key new tool beyond mosquito nets, insecticides and drugs in the battle against a disease that the WHO estimates killed 435,000 people in 2017. Children under the age of five in Africa are particularly vulnerable, accounting for about two-thirds of all deaths.

With kids in some regions getting multiple episodes of malaria in a year, even a partially effective vaccine could have a big impact, Mary Hamel, coordinator of the program for the WHO, said in an interview. The pilot is scheduled to start in Malawi next week and expand to Ghana and Kenya next. A decision to make the product more broadly available will likely be made within two to four years, Hamel said.

“A vaccine that is highly efficacious -- 90 percent or so -- that’s not in view at this point,” she said. “But this vaccine getting to where it is shows that a malaria vaccine can be made. It will be a pathfinder.”

Crispr Mosquitoes

The effort underscores the challenge of developing products for poorer countries that carry costs extending well beyond clinical trials and approvals, said Ashley Birkett, director of PATH’s Malaria Vaccine Initiative.

“There’s still another tranche of many, many tens of millions of dollars, possibly hundreds of millions of dollars and many years, before they’re out there being sold,” he said.

The main hurdle for the malaria vaccine is getting protection to persist for longer, Birkett said. Glaxo is working on a new approach in mid-stage studies that relies on the same basic vaccine formula but involves delaying one of the doses and reducing the amount of the antigen, according to Breuer.

Billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates, whose foundation has provided financial support for the global fight against malaria, said last year that eradicating the illness will depend on further progress in science and technology, including a technique for editing gene sequences called Crispr. The technology is already being used to breed mosquitoes that spread sterility to deplete their numbers.

The malaria parasite turns out to have greater genetic diversity than previously believed, compounding the challenge. A 2017 study of more than 600 children from a village in the West African nation of Gabon found that each was infected by a slightly different strain. Resistance to drugs and insecticides, meanwhile, is making efforts to eliminate the disease more difficult.

With more than 5,000 genes, it’s a complicated microbe, and the pursuit of a vaccine has led to numerous dead ends, Hamel said. Early development of the Glaxo shot began around 1984. As the pilot starts in Africa, scientists are looking to the potential next generation of technology.

“This is the first malaria vaccine,” she said, “not the last.”

To contact the reporter on this story: James Paton in London at jpaton4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Eric Pfanner at epfanner1@bloomberg.net, John Lauerman, Marthe Fourcade

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.