On Brexit, Macron Channels de Gaulle

On Brexit, Macron Channels de Gaulle

(Bloomberg) -- Maybe Charles de Gaulle was right all along.

The former French president and wartime resistance leader blocked the U.K.’s first attempt to join the then-European Community in 1963, arguing that England was too “maritime,” too “insular,” too “original” in its traditions and too tied to far-flung markets ever to be a good European.

Now, as Prime Minister Theresa May and a riven parliament try to figure out how to untangle the country from more than 40 years of European integration by a new deadline of April 12, France has again shown itself among the least willing of member states to accommodate London. As Britain teetered toward the precipice of a potentially catastrophic “no deal” exit last week, French President Emmanuel Macron held the line against a more forgiving schedule to avoid one.

If Parliament were to again reject the agreement the European Union negotiated with May, Macron told reporters outside Thursday evening’s summit in Brussels, a hard Brexit would follow. “This is it. We are ready.”

Nobody is even remotely ready, so the French position takes some explaining. The chaos of a no-deal Brexit would snarl French ports and trade. French customs officials this month went on a work-to-rule strike just to show how unprepared the government is, causing havoc for rail traffic to the U.K. France may only rank 15th of the 27 EU nations in the potential cost of a hard Brexit, according to Bloomberg Economics, but French jobs would be lost, too. Fishing fleets, in particular, could risk devastation.

Still, the message from Paris has at times seemed taunting, even impatient for the Brits to be gone. French Minister for European Affairs Nathalie Loiseau caused a stir after France’s Le Journal du Dimanche reported on a private Facebook post in which she said she’d named her cat Brexit: It meowed loudly to go outside, couldn’t make up its mind to leave when the door was open and then looked resentful when pushed out. It was a joke, she later explained (she doesn’t have a cat), but a sharp one.

The French attitude to Brexit can only partly be explained by commercial opportunism or political tactics. “It’s folkloric for so many French, it’s the old hereditary enemy that’s still not been fully digested. So much of our history is the opposition against England,” said former foreign minister Hubert Vedrine in a phone interview, adding that this was an Anglophobic view he does not share.

A popular French mythology of England as the enemy runs right back to the medieval Hundred Years’ War, in which English kings descended from the Norman conquest fought to assert their claims to the French crown. For every great victory taught in English schools (think Henry V decimating the French nobility at Agincourt in 1415), French schoolchildren learn of a victory (Orleans, 1429), a massacre (Limoges, 1370) or a martyr (Joan of Arc, 1431) of their own.

Beyond historical muscle memory, there’s a widespread misconception about the British obstructionism de Gaulle warned about, according to Vedrine. “For the French technocratic elite, there’s this idea that the mean English prevented us from building the United States of Europe. It’s a totally erroneous view,” because there was never an appetite for a federal Europe among Europe’s electorates, Vedrine said. That includes the French.

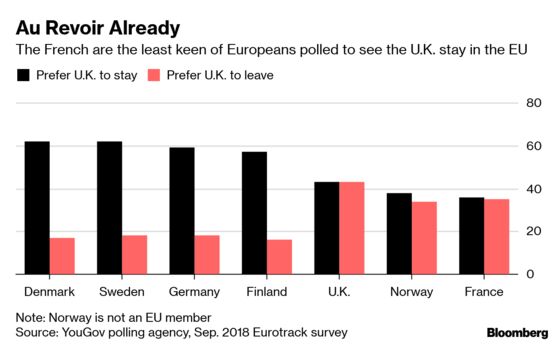

Ruing Brexit seems a minority view in France, however. Three opinion polls by the research agency YouGov over the last two years found the French to be the consistently least eager, among the EU citizens polled, to see the U.K. stay in the bloc.

Some French officials and business people see commercial opportunities in the U.K.’s departure, running advertising campaigns such as “Tired of the Fog? Try the Frogs!” to lure banks, bankers and businesses away from London. Domestic French politics are a factor, too, as Macron pushes back against Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party ahead of elections to the European Parliament in May. The far right sees the U.K.’s departure as validation of its own euroskeptic appeal.

More broadly, Macron has made a renewed drive for European integration a centerpiece of his political platform for delivering answers to the popular frustrations displayed by the Gilets Jaunes, or Yellow Vest, protest movement. He hasn’t waited for the U.K. to actually leave before pushing ahead with plans for a so-called European army and other integrationist projects that would never be possible so long as the U.K. wielded a veto inside the EU.

“Successive objections by the British since 1973 meant that a series of decisions were never taken” in the EU, said Axel Poniatowski, 67, a former head of the French parliament’s foreign affairs committee and son of one of France’s most influential officials in the 1970s. “They are above all traders, we are more landowners.”

Indeed, what de Gaulle had to say about England was largely correct, according to Robert Tombs, a professor of French history at Cambridge University and co-author of a book on the Franco-English relationship since 1688, with his French-born historian wife Isabelle.

The idea of England as France’s mirror opposite is deeply rooted in the so-called Second Hundred Years War of 1689-1815, which crystallized the rivalry as one between Europe’s emerging liberal, Protestant, mercantile sea power, and its greatest autocratic, Catholic and agricultural land power, according to Tombs. That collection of wars ended with defeat for Napoleon and his vision of a Europe organized by France, in large part due to Britain’s superior navy and its ability to raise funds for the war from the world’s budding financial center, the City of London.

But what role the British should play in France’s European project always was—and will remain after Brexit—a dilemma with far-reaching consequences for France in particular and the continent as a whole. “Get Britain out and keep them in a subordinate position on the periphery, which is essentially what the agreement [EU Brexit point man Michel] Barnier negotiated with Theresa May would do, and it will be easier to build the kind of Europe France wants,” said Tombs. “But you also then risk making France subordinate to Germany, which whatever anyone says is just bigger.”

What makes the relationship so strangely fraught is that France and Britain became, through their military, technological and intellectual competition and cross-pollination, among the most alike of Europe’s larger nations. Both once ran global empires and struggled since with their loss of position. Both are fiercely committed democracies that emerged as victors in the two World Wars with Germany. As a result, they are the only two EU nations with United Nations Security Council seats, nuclear weapons and a significant capacity and willingness to project conventional military force.

In 1940, at the height of France’s invasion by Germany, de Gaulle even agreed with then British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to merge the two states. The project failed as Churchill was preparing to travel to the signing ceremony, because the French cabinet refused to endorse it.

“It’s always fascinating to listen to politicians in France talk about republican values, and British politicians talk about British values, because they’re essentially the same,” said David Andress, chairman of the U.K.’s Society for the Study of French History. Much of the historical memory on both sides, he added, is artificial.

The real divide between Britain and France’s conception of the modern world came in 1956, when the U.S. put a humiliating end to a joint Anglo-French military operation to retake the Suez Canal, following its nationalization by Egypt. Washington threatened to create a run on the fragile British pound unless the U.K. withdrew. The incident cemented opposing lessons that the two fading colonial powers had drawn from their experience of the recent World War.

The lesson for the French was “that the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ were hell-bent on world domination, at the expense of France,” said Sudhir Hazareesingh, a lecturer in politics at Oxford University. For the British, it was “that the only future for a post-imperial and bankrupt Britain lay in close alliance with the Americans.”

Those different approaches echoed through disputes cross-Channel disputes ever since, including de Gaulle’s 1966 decision to pull France out of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s U.S. dominated military command, British opposition to Europe-wide military cooperation of almost any form outside NATO, and the respective British and French decisions to join and oppose the George W. Bush administration’s controversial invasion of Iraq, in 2003.

The same was true within the EU. France tried to chip away at the City of London’s financial dominance, and resisted the British push for a single market for services and the EU’s enlargement to include natural U.K. and U.S. allies in Eastern Europe. The two sparred perennially over how much of the EU’s spending should be spent on agriculture, a huge French priority still. That share began at about 80 percent of the bloc’s budget in the early years of the European Community, but has now fallen to 38 percent, in large part due to incessant U.K. opposition.

It’s a rivalry that seems unlikely to end, no matter what happens with Brexit on April 12.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Anne Swardson at aswardson@bloomberg.net, Paul Sillitoe

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.