(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For a country that’s vying with Qatar for the title of the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas, Australia’s domestic network can look remarkably dysfunctional.

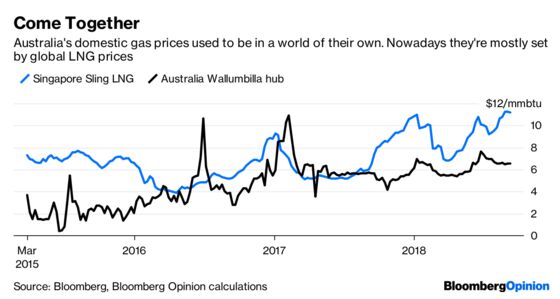

Prices at Wallumbilla — a pipeline junction point west of Brisbane that produces a gas benchmark similar to those at the Henry Hub in the U.S. and National Balancing Point in the U.K. — have more than tripled over the past three years. That’s caused angst among industrial and household consumers and prompted the seemingly bizarre situation where a country that’s a giant LNG exporter is looking to build terminals to import the liquefied gas in an attempt to balance the market.

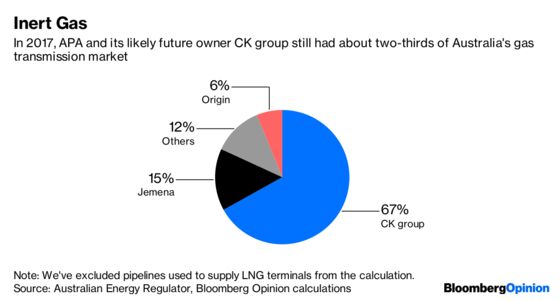

Of course, if you’re an owner of key assets, dysfunctional markets can be oddly attractive. Victor Li’s CK group of companies in June offered investors in pipeline operator APA Group A$13 billion ($9.2 billion) to buy the company, which has around two-thirds of the available capacity in Australia’s eastern gas transmission market. At 15 times last year’s Ebitda, that makes APA more richly valued than Apple Inc.

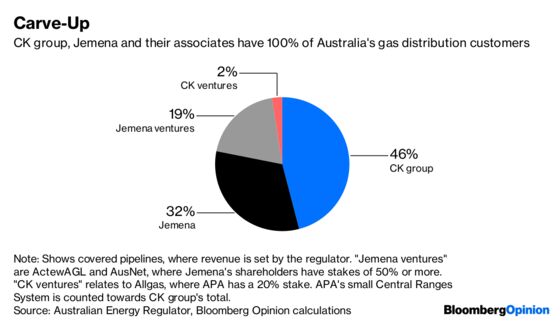

It’s not hard to see why APA would appeal to an investment group that’s always sought out monopoly assets with stable long-term cash flows. Once the deal is complete, almost the entire gas transmission and distribution network in the east of the country will be owned by just two players: Li’s CK group and the Jemena joint venture between State Grid Corp. of China and Singapore Power Ltd.

Why, then did the country’s antitrust regulator agree to essentially wave through the deal on Wednesday?

The best explanation is that it’s too late to unscramble this egg. At present, the transmission pipelines that connect major gasfields to consumers form a grid that’s mostly operated by APA and Jemena, while the distribution networks that link those trunk lines to individual buildings are a duopoly between CK and Jemena.

While allowing CK to take over APA would vertically integrate both markets, CK would only be able to use its market power in the transmission business to disadvantage Jemena by essentially switching off its own pipes — an abuse that would be so blatant as to be inconceivable, according to Rod Sims, chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

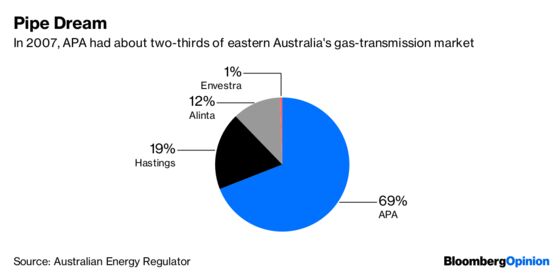

The real problem isn’t what this deal will do to the market, in other words, but what previous deals have done in turning APA into such a dominant player.

“A lot of people who complained about the acquisition were complaining about the market power APA already has,” Sims said by phone. “They’ve got that power anyway, and this transaction doesn’t change it.”

Pipelines are often considered a natural monopoly. Anyone contemplating building one needs to contend with the fact that the expenses needed to move their first cubic foot of gas between two places are vast and upfront, while the marginal costs for incumbent competitors are close to zero as long as there’s spare capacity in the tubes. The problem for Australia is that this situation is scaring away competitors, leaving the transmission network in the hands of CK group and Jemena.

There’s a potential solution, but it’s a long shot. As a condition of the deal, the ACCC is ordering the sale of a group of APA assets on the west coast, which has separate power grids from eastern Australia. If that could be bought by a company with experience developing pipelines and a knowledge of the local market — say, Canadian utility Atco Ltd., which already operates in Western Australia — then perhaps those additional cash flows and the presence of monopolistic profits in east coast transmission networks could encourage it to break up the duopoly with its own infrastructure.

The trouble is that while the ACCC can cross its fingers and hope, the regulator has limited powers to force such an outcome. The key problem in Australia’s energy markets in recent years has often been that powerful incumbent players with monopolistic positions have been able to outsmart regulators in pushing the rules to keep the rents flowing.

“The criticism has always been that regulated businesses have such an incentive to win the arm wrestle with the regulators that they’ll always employ the best people and have the most firepower,” said Tony Wood, director of the energy program at the Grattan Institute, a think tank. “It’s an issue of whether you think the regulator is good at their job or not.”

Even if the gambit works, Australia isn’t going to see gas prices fall back to their levels of a few years ago. Domestic prices have essentially reset to those on the global market, and are unlikely to head much below that. Perhaps a new player can be induced to build another pipeline in Australia — but the days of cheap gas are gone forever.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.