Danske Scandal Is Watershed Moment as Europe Wakes Up to Risks

Danske Bank is now the target of criminal investigations in Denmark and Estonia amid allegations that as much as $9 billion.

(Bloomberg) -- Europe can’t allow itself another money laundering scandal like the one engulfing Denmark’s biggest bank, according to a growing list of regulators, legislators and even bankers now demanding better region-wide controls against such crime.

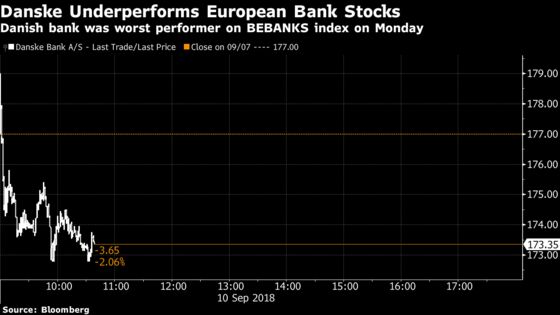

Rasmus Jarlov, the minister in charge of financial legislation in Denmark, says the example of Danske Bank A/S is one from which Europe needs to learn. The lender is now the target of criminal investigations in Denmark and Estonia amid allegations that as much as $9 billion, mostly from Russia, was laundered through its Estonian unit between 2007 and 2015.

Jarlov says it’s “absolutely” clear that there are “lessons that can be drawn from as significant a case as this one.” He also says he’s sure that there’ll be an exchange of information from the Danske case within the European Union, with the idea being to “ensure that we do all we can in Europe to prevent another” such case.

‘Illegal Acts’

The minister, who has been looking into the allegations against Danske together with Estonian authorities, says it’s now clear the amounts of money in question are “enormous.” He also says that “a lot suggests that things have happened that are illegal,” as investigators sift through the evidence.

Europe has seemed unprepared for the stunning revelations of large-scale money laundering apparently committed under its watch. Danske is just the latest bank found to have had inadequate procedures in place to prevent laundering, with the list including Deutsche Bank AG and ING Groep NV.

In May, EU First Vice President Frans Timmermans, Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis and Commissioner Vera Jourova asked Europe’s three supervisory agencies and the European Central Bank to find ways to improve cooperation between bank supervisors and anti-money laundering authorities.

Nordea Weighs In

The region’s biggest banks are also demanding better protections. Next month, the euro zone will get its eighth global systemically important bank, Nordea Bank AB. Its management is asking authorities in the bloc to consolidate anti-money laundering defenses.

Julie Galbo, chief risk officer at Nordea and a former regulator at the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority, says the problem with the current setup is that it relies on too many different legal interpretations and national agencies. As an example of holes in the system, Galbo notes that if one bank stops doing business with an entity it has identified as suspicious, there’s very little in Europe right now preventing another bank from picking up that business.

“You don’t have a body in Europe that harmonizes these things, you don’t have a body in Europe that supervises anti-money laundering implementation,” Galbo said in an interview. The “biggest effect” from coordinating regulation and monitoring at a European level would be “that you avoid arbitrage.”

An Aug. 31 EU analysis obtained by Bloomberg highlights some of the problems and underlines the need for greater centralization of powers to fight financial crime.

“As a supervisor working across many different national jurisdictions, the ECB must apply differently transposed EU legislation, potentially resulting in differences as to what input the ECB is entitled to receive from the AML supervisors and how such input can be integrated into the prudential supervisory processes.”

Correspondent Banking

In the case of Danske, flows through its Estonian unit seemingly came to a sudden halt after Deutsche Bank stopped offering Danske its correspondent banking services in the Baltic country.

Galbo declined to comment specifically on the Danske case. But speaking in general terms, she said, “You have seen examples where some banks have switched off the flow, streams of money, from particular regions and particular customers.”

“The bigger banks have shut down something that is then moving to other banks that are happy to accommodate, if you will, more dubious flows of money,” she said.

With an “effective European supervision, you could monitor when that happened and you could probably intercept it,” she said.

Moving to the Euro Zone

Nordea, which has itself been fined for money-laundering breaches in recent years, is set to move its headquarters to Helsinki next month, from Stockholm. The bank has said that a key reason for the move was to be inside a more harmonized regulatory environment.

Galbo says Nordea would welcome European agreement on the definition of a risky customer or a risky banking transaction. Under new regulations, lenders are expected to adopt a so-called risk-based approach to identifying and monitoring potential suspicious transactions.

“It’s fairly easy for those customer types that you know, those in your home country,” she said. “But if you sit somewhere else in Europe and you have to substantiate that elderly people in nursing homes in Denmark are low risk, would you do it? No, because you don’t really know them.”

--With assistance from Alexander Weber.

To contact the reporter on this story: Frances Schwartzkopff in Copenhagen at fschwartzko1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tasneem Hanfi Brögger at tbrogger@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.