Who’s in Charge of Protecting Social Media from Election Interference?

Behind the scenes, there is a delicate struggle over who is accountable for ensuring that another election isn’t compromised.

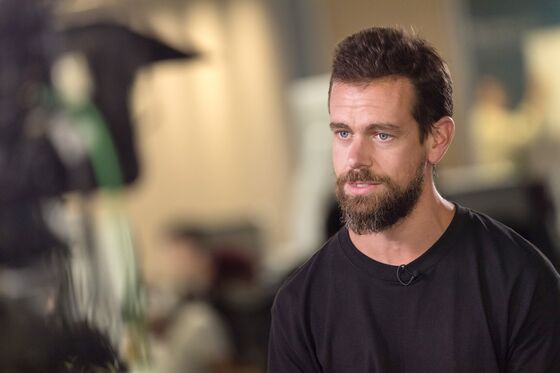

(Bloomberg) -- When Facebook Inc.’s Sheryl Sandberg and Twitter Inc.’s Jack Dorsey testify in front of the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee this week, there will be some punishing questions about how the companies are preparing for the upcoming elections.

The executives will aim to show full dedication to preventing the kind of interference that occurred in 2016, when Russian meddlers used the companies’ platforms to try to sway American votes. But they’ll also ask for more help. Because behind the scenes, there is a delicate struggle over who is accountable for ensuring that another election isn't compromised. Tech firms have been stymied in efforts to get federal agencies to provide the kinds of assistance that can only come from officials who have access to sensitive national security information, according to people familiar with the matter. The government has made it clear that the companies need to do more to prevent hacking and improper influence.

Federal agencies have been hesitant to share confidential tips that could identify or prevent the next Russia-scale attack because of security concerns, according to the people, who asked not to be identified because they weren’t authorized to speak about the matter. The intelligence community assumes the companies already know what to look for, said the people. When the companies do ask for help, they sometimes don’t know who to call, because there’s not a single person or entity in charge. In May, the White House eliminated the role of cybersecurity coordinator. In late August, a Facebook security official invited representatives from other technology companies including Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Microsoft Corp. and Amazon.com Inc. to a meeting at Twitter’s San Francisco headquarters, to share strategies and tips for detecting problems ahead of the midterms. Nobody from the government was invited, one of the people said.

Garrett Marquis, a National Security spokesman, said the National Security Council’s staff is coordinating the federal government’s approach. “The president has made it clear that his administration will not tolerate foreign interference in our elections from any nation state or other malicious actors,’’ he said.

When it comes to policing Facebook’s platform, “it’s a little unclear exactly which parts of that the government should be involved in, and given the particular administration we have, it's not necessarily clear that they have their interest aligned with what the public wants for these platforms either,” said Dean Eckles, an assistant professor at MIT Sloan who focuses on communication technologies and used to work at the social network.

Facebook has had a lot of catching up to do. A couple years ago, it had few systems to proactively search for bad behavior, and didn't look for coordinated social manipulation by impersonators. The company typically waited for its users to report the worst activity, and then would send those posts to moderators to take them down if they violated company policy on violent content, nudity or hate speech.

For months after the 2016 election, Facebook said it had no reason to believe Russia bought any political ads. Facebook learned about the Internet Research Agency, the agency that ran the campaign, from the media, not the government, according to people familiar with the matter.

Facebook has now unveiled a series of updates, tools and rules that it says will help prevent copycat attacks. But the company is limited in what it can accomplish, since Facebook can’t see what happens in the real world, and doesn’t know enough to guess the motivations or intent of foreign powers, Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook's chief executive officer, said on a recent call with reporters. In Wednesday’s testimony, Facebook plans to list all the ways in which it has shared information before briefing the Senate committee on its limitations. “We don’t have all the investigative tools that the government has,” Facebook’s Sandberg plans to say, according to written testimony released by the company.

Yet government officials have indicated that Facebook is in a better position to assess the risk. On July 31, Facebook said it had found a new coordinated threat on its network. A group of people with fake identities had tried to organize political events, including a counter-protest of a rally by the Unite the Right group, known for sparking violence in Charlottesville, Virginia last year. The company briefed Congress, including Senate Intelligence Committee chair Richard Burr, about its findings. Asked by a reporter if Russia was behind the latest effort, Burr deflected. “I’ll let Facebook be the ones to really analyze or make attribution to who was behind it,’’ he said.

The company’s discomfort with this position was clear from its remarks that day. "We have shared our technical details with law enforcement and we believe law enforcement and the intelligence community will have a lot more data upon which they can draw -- and if they want to make an attribution decision, that’s up to them,’’ Alex Stamos, the head of security, said on a call with reporters on the day of the announcement.

With less than 10 weeks until the U.S. midterms, this game of political hot potato— the passing of responsibility between companies and the government— is leading to the uncomfortable conclusion that nobody has the full picture.

Stamos has since left Facebook for a job teaching cybersecurity at Stanford University. Last week, he published a blog post warning that it was already too late for the U.S. to protect the 2018 election. He argued that while the government is happy to blame tech companies for failing to see the threats, the government itself is just as much – or more – at fault.

“Although by now Americans are likely inured to chronic gridlock in Congress, they should be alarmed and unmoored that their elected representatives have passed no legislation to address the fundamental issues exposed in 2016,’’ he wrote.

Rhode Island’s Senator Sheldon Whitehouse said at an August Judiciary Committee hearing on securing critical infrastructure that the diffuse approaches to cybersecurity in the White House and in Congress concern him. He said he fears a "cyber catastrophe" could occur because "everybody is waiting for somebody else to make the first move and it all goes off."

Amid the dire warnings, there are some signs of improved relations. Facebook has been hiring former intelligence agents, hoping that their security clearance and existing relationships will help enhance the flow of information. The company recently announced the discovery of another smaller online misinformation campaign from Russia, crediting the government for their help. The FBI remains in close contact with technology companies, and last spring attended another meeting of tech firms, organized by Facebook. “We’re spending so much of our effort trying to engage with the social media and technology companies, because there is a very important role for them to play in terms of monitoring and, in effect, policing their own platforms,’’ FBI director Christopher Wray said in an August 2 press briefing, adding that they are sharing “actionable intelligence in a way that wasn’t happening before” the 2016 election.

If the government puts too much faith in Facebook solving the problem, it won’t be very successful, said Eckles, from MIT. Facebook sees one side of the activity, but the government knows what happens in the real world, and understands what to look out for. When the company sees suspicious activity start to percolate, how can it draw the line between a few people trying to spread fake news and a national security threat?

“Who possesses all the information required to make that determination?’’ Eckles said. “Some of these questions may remain unanswerable.’’

For more on social media security, check out the Decrypted podcast:

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Emily Biuso at ebiuso@bloomberg.net, Jillian Ward

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.