This Group Teaches Kids to Love Guns, and U.S. Taxpayers Foot the Bill

This Group Teaches Kids to Love Guns, and U.S. Taxpayers Foot the Bill

(Bloomberg) -- In the middle of Alabama sits a $20 million shooting range run by a group that’s largely financed by the American taxpayer. It is, to be accurate, a spread of rifle and pistol ranges designed with state-of-the-art targets and electronic scoring, set under a canopy of trees on country club-like grounds. A fleet of gleaming golf carts zooms across 500 acres, tricked out with custom rifle holders to prevent mishaps on the rolling terrain.

This facility is run by the Civilian Marksmanship Program, or CMP, an understated pro-gun group with a quarter-billion dollars in assets. Most of that wealth—far more than the National Rifle Association Foundation has—effectively comes from the continuing generosity of the federal government. CMP is the U.S. Army’s designated retailer of cast-off weapons, making it a nonprofit with a very profitable franchise. The next big payday will come later this year when CMP starts selling thousands of M1911s, the U.S. military’s sidearm of choice for more than 70 years.

Talladega Marksmanship Park, as the Alabama site is known, sits within the same 15,000-person town that’s home to a Nascar Superspeedway. Although visitors pay as much as $30 to get inside, the park hasn’t made money since it opened in 2015. The complex is an embodiment of CMP’s self-declared purpose: “To promote firearm safety and marksmanship training with an emphasis on youth.”

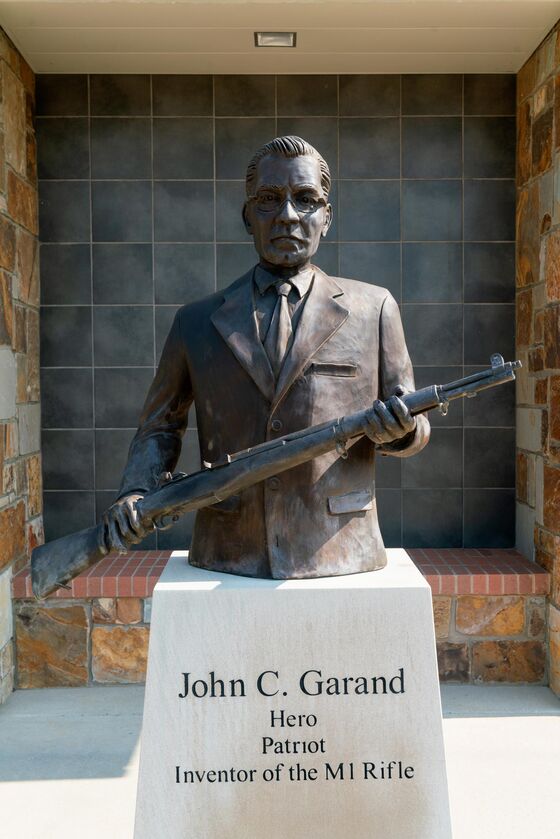

A trailer emblazoned with that mission statement and photographs of children holding rifles sits atop a hill overlooking the long range. The display is flanked on one side by the stand of a local barbecue joint with a banner that reads: “A’int gotta have no teeth to eat my meat.” Down the hill there’s a statue of John C. Garand, a gun inventor who is a sort of patron saint of CMP.

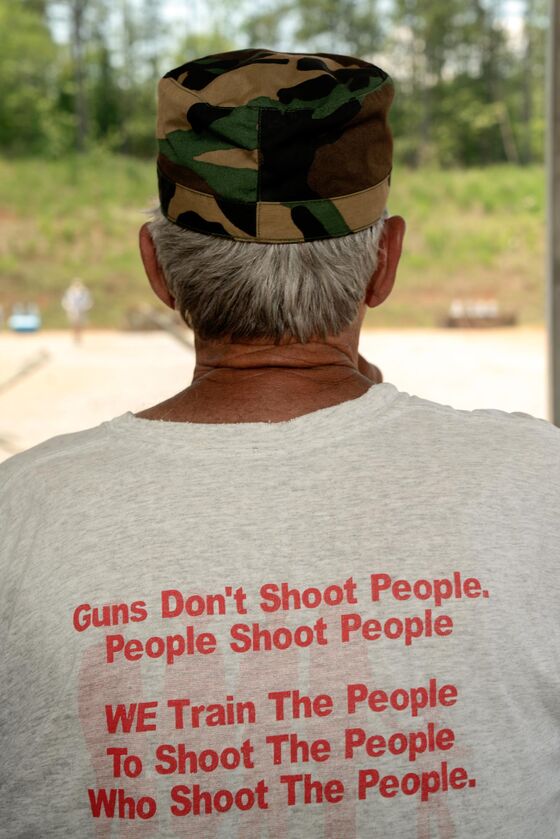

A missionary sensibility has been at the center of the organization since its founding as a civilian-preparedness division of the U.S. Army at the turn of the last century, but the emphasis on children is a modern-day shift. The young people who today participate in air rifle competitions and take the group’s junior shooter safety pledge and make pilgrimages to its resplendent marksmanship park will grow up to be adults who know guns, shoot guns and amass collections of guns. Some, naturally, will join the CMP’s cousin, the National Rifle Association.

If CMP accomplishes this mission, every child touched by its outreach programs will do his or her part to participate in gun culture across the country for decades to come. And we, the people, will have helped pay for it, regardless of our views on guns, through the highly unusual gift of second-hand military rifles and pistols.

The M1 Garand is a hefty, wood-encased semi-automatic rifle recognizable even to those who can’t distinguish .30 caliber from 7 millimeter. Prop versions have been pointed at people pretending to be Nazi soldiers in uncountable Hollywood movies. This is the gun that defeated the Axis powers and accompanied American soldiers into the early days of the Vietnam War. And for more than six decades, CMP has been the Army’s chosen vendor for sales of the famous rifle.

CMP started to bring batches of used M1 Garands onto the market at least as far back as 1956. For decades after that you could buy a refurbished rifle through the group for less than $200. By the 1990s, prices had increased to between $400 and $750, depending on condition, according to an article at the time in Small Arms Review. During a recent visit to CMP’s gun shop in Anniston, Ala., where the group has its headquarters, many of the M1s on display had price tags around $1,000.

“The firearms are a meal for us,” says Mark Johnson, CMP’s chief operating officer. “We sell the firearms. We make a profit on the firearms. The excess goes into our endowment.”

Records reviewed by Bloomberg show that CMP has received thousands of vintage rifles and other items from the U.S. military worth more than $300 million over the past 16 years. The nonprofit had assets worth $231 million in 2015, according to its most recent Internal Revenue Service filing, including an investment portfolio worth $180 million.

At a time when Americans are sharply divided over the place of firearms in society, the U.S. government has, in effect, subsidized the metamorphosis of CMP into a deep-pocketed, nationwide evangelist for youth gun culture. The group has survived and thrived, despite repeated attempts by politicians to shut off its gun pipeline.

CMP describes its wealth as a hedge against any future in which the Army’s old guns are no longer given to the group. “We’ve been preparing to run out of firearms,” says Johnson. “From Day One we were preparing to run out.”

That fear is not without merit. At the time CMP was spun off from the Army into a nonprofit in 1996, the group received $77 million in government assets, including guns and ammunition. Paul Simon, a Democratic senator from Illinois, described the move at that time as an “incomprehensible, irresponsible baffling boondoggle for the NRA,” according to the Congressional Record. Two decades later, studies by Rand Corp. and the Comptroller General are underway to assess whether CMP should continue to receive surplus weapons.

“We don’t know what legislation might be passed in the future,” says Judy Legerski, CMP’s chief executive officer.

The gun giveaways won’t stop soon. An amendment in a defense-spending bill signed by President Donald Trump in December requires the U.S. Army to transfer a cache of up to 18,000 retired M1911 pistols to CMP over two years. The measure was sponsored by Representative Mike Rogers, whose district includes Talladega. The congressman’s efforts on behalf of CMP have received recognition from Christopher Cox, the NRA’s chief lobbyist, who’s known to hold the ear of the president.

“This amendment is a win-win for the taxpayer,” Rogers said at the time. His office did not respond to requests for comment. Catherine Mortensen, a spokesperson for the NRA, credited the legislation with ensuring “these vintage pistols will be sold to law-abiding Americans rather than be destroyed at taxpayer expense.”

CMP will pay the Army only for the cost of transferring the M1911s. After refurbishing the pistols, it expects to sell them to the public, beginning this fall, for $850 to $1,050 each.

Advocates in Congress, including Rogers, have long suggested that offloading surplus weapons to the group saves the government money on storage costs. CMP’s leadership also takes that line. “Part of the goal is, when we sell antique Army weapons, we save the Army a great deal of money,” says Legerski.

It costs about 61 cents per year to store each disused pistol, according to an Army spokesperson. The government could save on the storage costs by selling the weapons to the highest bidder—and sending the money to the U.S. Treasury.

“It’s a multimillion-dollar giveaway,” says Representative Jim Langevin, a Democrat from Rhode Island who was paralyzed by an officer’s errant bullet while working as a police volunteer. “It’s not only an earmark that should go through the congressional appropriations process, but it will make our communities more dangerous by putting handguns onto our streets.”

The Defense Department has also expressed concerns. Eric Fanning, who served as Army secretary under President Barack Obama, says the Army wanted to find additional M1 rifles for CMP to sell, rather than turning over the old pistols. “We were concerned that there were no controls for handguns that ultimately would be traced back to the Army,” says Fanning, who now heads the Aerospace Industries Association. “We believed the risks were too high.”

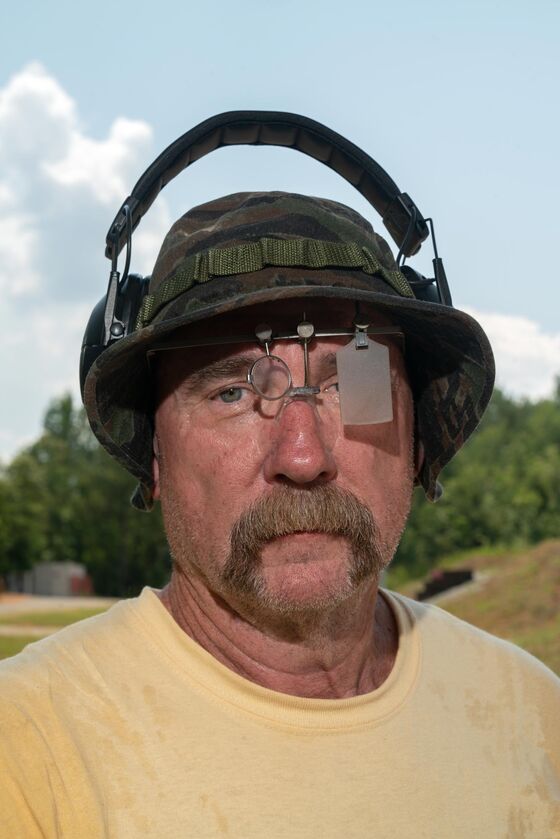

Months before CMP opened the M1911 crates, collectors were already clamoring for a chance to buy one and CMP plans to hold special auctions for an unknown number of the weapons that can be traced to historic events or notable owners. The demographic that will likely drive sales traveled to the CMP Talladega Marksmanship Park for a D-Day memorial shooting event inJuly, some dressed in full WWII re-enactor kits.

Herb Rosenbaum, 70, brought along an M1911 he had purchased years ago. The historic pistols are available but relatively scarce. His friend, Michael Glasman, is planning to purchase one when CMP’s sale begins. A thousand-dollar price tag isn't a deterrent—he considers it fair for an antique pistol—although he has been surprised to see the climbing prices of M1s in recent CMP sales. His first M1 cost little more than $300.

“My parents were in concentration camps,” says Glasman, a 62-year-old from Tennessee. “They were liberated by soldiers with M1 Garands.” He now participates in shooting competitions with the rifle.

CMP could pull in as much as $18 million from the sale of the M1911 pistols, about enough to pay for another sprawling marksmanship park. “We are very good stewards of our good fortune,” says CMP’s Johnson. “We are very careful with the dollars that we make from the guns.”

The origins of CMP date back more than a century and have little to do with selling off disused military weapons or working with children. President Theodore Roosevelt worried about the national ability to wield guns. He had led the Rough Riders into battle during the Spanish-American War before he became commander-in-chief of the then-85,000-person U.S. military. If a big war came and civilians had to be drafted, Roosevelt wanted to be sure inductees could shoot straight.

So he joined forces with General Bird Spencer, then the president of the National Rifle Association, to advocate for a program that would provide firearms training outside the military. In 1903, Congress set up CMP’s predecessor as a program overseen by the U.S. Army.

As the active-duty and reserve ranks grew, the need to train civilians evaporated. A 1990 report by the General Accounting Office said the program, still a part of the Army, was “of limited value.” After nearly a century of trying to prepare Americans for war, Roosevelt’s vision had become obsolete.

Yet legislators never quite wound down the civilian training program or blocked its access to military resources. That effort was aided by strong support from the NRA, which practically ran the office during its Army years, according to Carol X. Vinzant’s book, Lawyers, Guns and Money. Gun sales started in this period, and until 1968 only NRA members could buy surplus rifles from the marksmanship program.

When Congress in 1996 moved to spin off what had been a small Army office into a freestanding nonprofit, legislators allowed the transfers and sales of used firearms to continue. Today, even though NRA membership isn’t required, CMP customers looking to buy an old military gun must belong to one of over 2,000

groups. Many of them are also NRA affiliates.

The NRA and CMP are, in some sense, two sides of the same coin. One is hyper-political, the other shuns anything with a whiff of lobbying. One is funded entirely by corporate and civilian gifts, the other largely by government handouts. But both share an underlying goal and have staged joint marksmanship events for over a century.

“We’ve always known the NRA is out there carrying that Second Amendment torch, and we benefit by that,” says CMP spokesman Steve Cooper. “We’ve been good—I won’t say partners, but we’ve been good sponsors and advocates of the shooting sports over the years.”

For the woman running CMP, keeping the guns coming in is the key to funding the many programs the group uses to spread gun culture. And the key to keeping the guns coming is to gain support from political allies, such as Rogers, without becoming a political lightning rod like the NRA.

There’s a reason few people outside the gun world have heard of CMP. Legerski, 72, has learned to play a quiet but influential role in public life. The Wyoming resident organized political campaigns for Dick Cheney and served as a civilian aide to the secretary of the Army. She was appointed to CMP’s board at its creation as a nonprofit.

As part of her mission to ensure CMP endures, Legerski has kept its activities apolitical and allowed others to carry water on Capitol Hill. “We don’t lobby or hang around asking for things,” she says. At the same time, CMP has built good will by undertaking good works, such as refurbishing ceremonial M1s for military funerals, while methodically building up financial reserves that could likely cover operating expenses for a decade or more.

“We do try to plan responsibly,” Legerski says. “To provide services, junior ROTC, train instructors, certify ranges and host national rifle competitions, it all costs money.”

To many supporters on Capitol Hill and elsewhere, CMP’s most endearing quality may be its work with grassroots programs, especially for kids. It cooperates with such outside organizations as A Girl & A Gun, a women-only shooting group, and a breast cancer charity called Shooters for Hooters, along with thousands of other local clubs and youth programs. CMP hauls a mobile marksmanship range to events around the country.

The support for CMP is vital to scores of small organization. At Ridgecrest Summer Camps in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, the firing range for campers relies on CMP to train its shooting instructors, says executive director Art Sneed. Northland Sportsmen’s Club in Gaylord, Michigan, has been operating firing ranges staffed by volunteers for 84 years. A few dozen children complete its instructional courses each year, finishing with a graduation pizza party. “It’s heartwarming to watch these kids come in,” says board member Jim Yeoman.

Even at the Talladega Marksmanship Park, where the focus is on adults, children are observers and participants. One young boy, the son of a CMP staffer, was excited to have fired a Tommy gun during a D-Day re-enactment. Over at CMP’s Anniston headquarters, about 20 miles from the marksmanship park, there’s a children’s camp hosted at its air rifle range and a retail store that does a heavy business in M1 rifles. Fifteen of the old weapons are purchased each day, on average, with the proceeds flowing back to CMP. Customers appear antsy for the next Army hand-me-down.

“Please do not ask about 1911s. We do not have any information at this time,” a sign at the shop advises. “Thank you for understanding.”

--With assistance from Anthony Capaccio.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Aaron Rutkoff at arutkoff@bloomberg.net, Jeffrey Grocott

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.