Two-Cent Fares Are Killing Airlines in India's Cutthroat Market

Indian carriers pay the world’s highest jet-fuel prices, thanks to local taxes of as much as 30 percent.

(Bloomberg) -- Global carriers have flocked to India, lured by a domestic travel boom and what’s expected to be the world’s third-biggest aviation market by 2025. Yet India has proven an intensely competitive market, where profits are scarce and the life expectancy of weaker airlines is anything but certain.

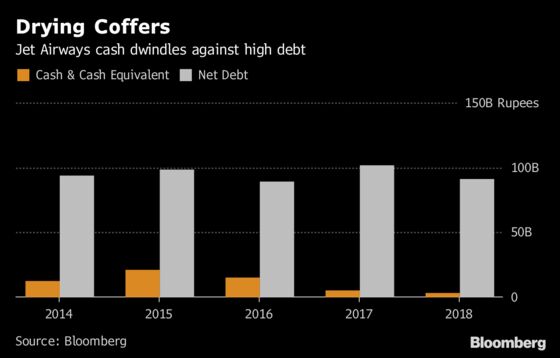

Jet Airways India Ltd., one of the first carriers to launch after the market opened up in the early 1990s, said in a filing this month that it needs cash to meet liquidity requirements. Its stock price is in a free-fall as losses piled up. The company’s board announced a turnaround plan Monday with scant details, including the sale of its stake in its loyalty program and reduction of 20 billion rupees ($285 million) in costs over two years.

It’s the latest sign of financial distress in a market beset by a crushing fare war that’s made life difficult for foreign carriers, ranging from Malaysia’s low-cost AirAsia Group Bhd. to Singapore Airlines Ltd., not to mention a teeming field of domestic players. The competition is set to intensify if Qatar Airways follows through with its proposal to start a short-haul airline in the country.

Jet Airways to Cut Costs, Sell Stake in Loyalty Plan for Revival

The Indian commercial aviation industry has pretty much been in shakeout mode ever since the government ended a state monopoly enjoyed by Indian Airlines in 1994. Debt-burdened Kingfisher Airlines ended operations in 2012 -- and 10 other domestic carriers remain locked in a largely profitless struggle for passengers, despite operating in the world’s fastest-growing market.

Real Killer

Indian carriers pay the world’s highest jet-fuel prices, thanks to local taxes of as much as 30 percent. But the real killer has been a protracted fare war that’s driven ticket prices so low that they can hardly cover costs.

“It’s a buyers’ market at the moment,” says Conrad Clifford, vice president for Asia Pacific at the International Air Transport Association. “While India has experienced 46 consecutive months of double-digit (passenger) growth, it is still a challenging market for airlines to operate in.”

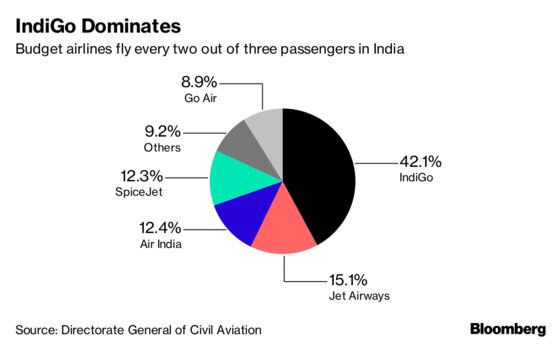

With the entry of budget carriers such as IndiGo and SpiceJet Ltd. since the mid-2000’s, full-service carriers like Jet Airways that have higher overhead costs -- for in-flight meals and entertainment -- have been forced to offer discounts to passengers looking for a great bargain.

For instance, in 2015, SpiceJet offered base fares of as low as 2 cents. Average ticket prices for New Delhi to Mumbai, the world’s third-busiest route, fell 15 percent to 3,334 rupees in July-August from the previous year, according to online travel agent Yatra.com. Fares are down 40 percent from 2014, according to Sanjiv Kapoor, the chief commercial officer of Vistara, Singapore Air’s local venture. That compares with a premium rail service for the same route at 4,075 rupees.

Such fares are “not sustainable,” yet there’s “no choice” but to keep offering them, Rahul Bhatia, the billionaire co-founder of InterGlobe Aviation Ltd. that operates IndiGo, told analysts last month after almost all of its quarterly profits were wiped out.

To Robert Mann, the New York-based head of aviation consultancy R.W. Mann & Co., the Indian market now resembles that of the U.S. three decades ago after the government freed ticket prices from federal controls in 1978, setting off a fare war.

“But in India, it has persisted for decades,” says Mann. “A fragmented airline industry competes away any scant, potential profits earned.”

Tight Lid

Still, not all Indian carriers are losing money. IndiGo, which started in 2006 with a focus on on-time flights and ultra-cheap tickets, has managed to keep a tight lid on costs.

Commanding discounts with big plane orders and lease-back deals, IndiGo has never lost money since going public in 2015. Its fleet of planes is also newer and more fuel-efficient than many rivals.

In contrast, Jet Airways is bogged down by higher costs. Besides carrying the burden of being a full-service carrier, the average age of its fleet is almost nine years, costing more to maintain.

Jet Airways Chairman Naresh Goyal, who started the carrier in 1993 when he was a little-known ticketing agent, told shareholders on Aug. 9 that he was “embarrassed” by the poor performance of the airline. The stock, down 66 percent in 2018, is headed for its worst year since 2011.

Group cash holdings at Jet Airways, in which Etihad Airways PJSC owns a 24 percent stake, dwindled to $46 million at the end of March, the lowest since at least 2008. It needs to repay about $445 million of debt coming due by March 31.

The market share of Jet Airways has more than halved to 15 percent from as high as 36 percent in the mid-2000s. It has reported profit in only two of the last 11 financial years, thanks to low oil prices.

The aviation industry is no stranger to the vicissitudes of fuel prices and fierce competition. They have landed other regional airlines in trouble as well before. Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd. and Singapore Airlines, the two premium Asian carriers, are in the midst of a transformation to help bring them back to a path of sustainable profit.

In contrast, Air India, the state carrier, is surviving on bailouts and no bidder showed interest when the government wanted to dispose of some of its assets this year. AirAsia, which entered in 2014 with a vow to break even in four months, is still nowhere close to its goal. Vistara, Singapore Air’s joint venture with the Tata Group that started in 2015, has yet to make any money. SpiceJet almost collapsed the previous year.

“The cost of running an airline in India is not adequately compensated by fare inputs,” says Kapil Kaul, chief executive officer for South Asia at Sydney-based CAPA Centre for Aviation. “That is the fundamental issue.”

--With assistance from Debjit Chakraborty.

To contact the reporter on this story: Anurag Kotoky in New Delhi at akotoky@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sam Nagarajan at samnagarajan@bloomberg.net, Brian Bremner

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.