Billionaire's Banking Empire Weighed Down by Massive Odebrecht Scandal

Billionaire's Banking Empire Weighed Down by Massive Odebrecht Scandal

(Bloomberg) -- Colombia’s drawn-out investigation into a continent-wide bribery scheme by Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht SA is casting a shadow over the nation’s biggest banking group, owned by one of Latin America’s richest men.

Grupo Aval Acciones y Valores SA and a subsidiary have seen their shares underperform since Odebrecht admitted to one of the largest graft cases in corporate history, detonating scandals across Latin America. One of Aval’s companies, Corficolombiana, partnered with Odebrecht on its biggest Colombia project: a section of the $2.5 billion highway known as Ruta del Sol. Odebrecht paid millions in bribes to win the contract, while Aval has repeatedly said it was unaware of the illegal payments.

In December 2016, Odebrecht said it paid $788 million in bribes across 12 countries, including Colombia. The company has reached settlements with Latin American governments including the Dominican Republic, Peru and Panama. But Colombia’s investigation drags on, causing investors to fret.

“It is possible that information damaging to us and our interests will come to light in the course of the ongoing investigations of corruption by Colombian authorities,” Aval said in a U.S. filing this year.

Sluggish Stock

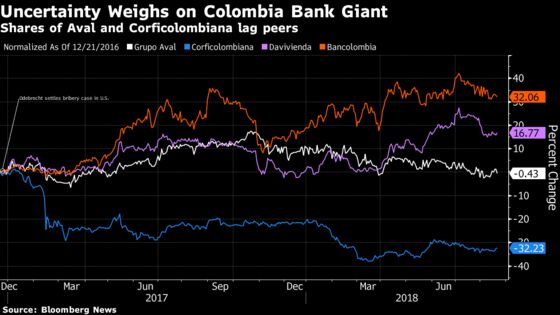

Aval, a suite of financial companies, was founded by Luis Carlos Sarmiento, 85, whose estimated net worth of $12 billion makes him Latin America’s seventh-richest person. But Aval shares, traded in New York and Bogota, have been essentially flat since Odebrecht divulged its bribes. Meanwhile, its own Banco de Bogota and peers like Banco Davivienda SA and Bancolombia SA are up by double digits. Shares of the Corficolombiana subsidiary have fallen 32 percent.

“All the news related to these investigations of Odebrecht without doubt will continue generating uncertainty, and we’ll see it translating into what we’ve seen over the last year or two in terms of share trading,” said Jose German Cristancho, head of research and strategy at Corredores Davivienda, a Bogota brokerage owned by the competing bank.

The stock is being affected by concern that the Odebrecht scandal could spill over to its partner. “That’s what ‘the market’ appears to believe, based on the underperformance of the stock vs. peers,” said Andres Soto, Santander Investment Securities head of Andean equity research.

For years, Odebrecht’s bribery machine operated across Latin America, doling out payments to politicians and government officials that helped it win contracts to build power plants, highways, airports, dams and other public works. It often created fake consulting, construction and engineering companies that billed for work that was never done. Money channeled through those companies went into graft.

Odebrecht’s scheme collapsed in December 2016 when it settled with U.S. Brazilian and Swiss authorities for what U.S. Department of Justice described as the “largest foreign bribery case in history.”

In Colombia, an investigation that began that year revealed that Odebrecht paid at least $32.5 million in bribes to win six government contracts and related financial transactions from 2009 to 2014. Ruta del Sol was among the largest.

Star-Crossed Partnership

A consortium of companies, called Concesionaria Ruta del Sol II, had been formed to build the second section of the road. Odebrecht held about 62 percent, Corficolombiana about 33 percent and a local construction firm the remainder. The contract, suspended after the bribery scandal, is now the subject of arbitration in a Bogota court to determine companies’ compensation for their work.

According to emails submitted to the court and seen by Bloomberg News, Odebrecht made payments from Ruta del Sol II accounts to contractors that caught the attention of the Corficolombiana’s controller on the project, Jorge Enrique Pizano, as early as mid-2015. Pizano questioned Odebrecht about the payments because they didn’t conform to auditing standards.

It is unknown whether those payments were part of Odebrecht’s illicit scheme. But Colombian prosecutors later discovered that bribe money had been channeled through at least two of the contractors.

Aval’s investor relations chief, Tatiana Uribe, said in a statement to Bloomberg News that at the time the company “had no knowledge that Odebrecht was corrupt.”

Nonaggression Pact

Corficolombiana pressed Odebrecht to explain the contracts. When it couldn’t, Odebrecht agreed to return the amount in question -- about $11 million -- to the partnership building the highway, Uribe said.

In exchange, Corficolombiana agreed not to sue Odebrecht over the payments. That contract was published last month by Colombia’s most influential news magazine, Semana.

Colombia’s investigation into Odebrecht has ensnared nearly three dozen politicians and company officials, including the CEO of Corficolombiana itself, who was arrested last year and is awaiting trial.

Assistant Attorney General Daniel Hernandez, who has spearheaded the criminal probe, said in an interview that prosecutors have no evidence that other Corficolombiana executives or other Colombian firms were involved in Odebrecht’s plot.

Still, a miasma of doubt surrounds Aval and its subsidiary. Corficolombiana’s shares are cheap, but “we’d have to have a resolution to all of this for one to think that the value of the equity could recover,” said Cristancho of Corredores Davivienda.

To contact the reporters on this story: Matthew Bristow in Bogota at mbristow5@bloomberg.net;Ezra Fieser in Bogota at efieser@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Stephen Merelman at smerelman@bloomberg.net, ;Daniel Cancel at dcancel@bloomberg.net, Andrea Jaramillo

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.