(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As President Donald Trump increasingly strains ties with U.S. allies, German leaders, including Chancellor Angela Merkel, have suggested that their country and other European nations should take steps to lessen their dependence on America. Now, Foreign Minister Heiko Maas has called for the creation of “U.S.-independent payment channels” to help shield European companies from unilateral U.S. sanctions such as the ones Trump has imposed on Iran.

That may sound unrealistic given U.S. dominance in financial markets: Any such payment channels would have to go through financial institutions that don’t have exposure to the U.S. dollar. According to the Bank for International Settlements, non-U.S. banks’ $12.6 trillion of dollar-denominated assets rival those of U.S. banks. Although European banks cut their dollar exposure by 42 percent between 2007 and 2017, they still have big positions: German banks’ outstanding dollar claims at the end of the first quarter of 2018 reached $502 billion.

The German foreign minister’s plan wouldn’t be impossible to put in practice, however: Banks without any U.S. exposure exist and, under certain conditions, can even grow.

The foreign minister’s call for a “balanced trans-Atlantic partnership,” first published in the German business daily Handelsblatt, isn’t focused on the economy alone. “That the Atlantic has grown wider politically is by no means just because of Donald Trump,” Maas wrote. “The U.S. and Europe have been drifting apart for years. The overlap in values and interests that has shaped our relationship for two generations is growing smaller.” Europe should seek a new type of relationship, in which the bloc remains a partner with the U.S. but serves as a counterbalance “where the U.S. oversteps red lines.”

As examples of these “red lines,” Maas cited Trump’s punitive import tariffs, the repatriations of billions of dollars in profit from Europe by U.S. based tech giants (“keyword: digital tax,” Maas wrote), the lack of U.S. enthusiasm for the United Nations and the U.S. pullout from the Iran nuclear deal. The latter that requires Europe to achieve greater financial independence, he said.

For the moment, European governments can’t do much to offer protection from unilateral U.S. sanctions for large companies with U.S. exposure or dollar funding. Many of these firms, including automakers Renault, Peugeot and Daimler and oil major Total, have put Iran-related plans on hold. It’s not clear that smaller companies with no interest in the U.S. market could pick up enough of the slack to keep the Iran deal alive. But there are ways to finance and clear trade between Europe and Iran. European countries need to find banks willing to give up the dollar and any involvement in the U.S. financial system in exchange for incentives related to working with sanctioned entities.

Europe might want to look to Russia for examples.

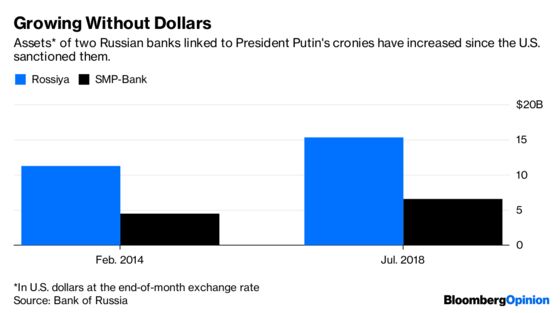

In March, 2014, the U.S. sanctioned the Russian bank Rossiya, whose shareholders include President Vladimir Putin’s wealthy cronies. It lost the ability to deal with U.S. banks and, according to The Wall Street Journal, had $572 million frozen in its U.S. accounts. In April, the U.S. imposed similar restrictions on SMP Bank, part-owned by Putin’s friend Arkady Rotenberg. The penalties didn’t kill either of the well-connected lenders; in fact, their assets swelled in dollar terms even as they had to give up the U.S. currency.

Rossiya’s assets grew faster than those of the state-owned lender Sberbank, the biggest in Russia. Sberbank is forced to stay away from Russian-annexed Crimea by the threat of U.S. sanctions that are as strict as those affecting Rossiya and SMP Bank. Freed from such concerns by U.S. sanctions, Rossiya unrolled a big retail banking project there and started financing development projects on the peninsula in the absence of significant competition. Both Rossiya and SMP Bank have received support from the Russian government and state-owned companies, which have placed large deposits with them.

If Europeans are serious about establishing “U.S.-independent payment channels,” they need banks such as Rossiya and SMP that are private or government-controlled. Whether such financial institutions exist or can be set up depends on how serious European governments are about busting extraterritorial U.S. sanctions. The German government, at least, should be serious enough: its economic interests diverge widely from those of the U.S., Trump or no Trump. Dealing with U.S. adversaries such as Russia and Iran can be more attractive to some German companies than acquiring U.S. exposure.

It remains to be seen whether European leaders have the courage to move in the direction Maas described. That would be a leap into the unknown, and would inevitably be seen by the U.S. as an escalation. But if Europe hopes to play a counterbalancing role to the U.S., it needs to move beyond newspaper articles, even those written by powerful foreign ministers.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at mberley@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.