British Doctors Lack Transparency Where Big Pharma Pays

U.K. Doctors Can Get Paid by Big Pharma and Keep Out of Sight

(Bloomberg) -- Half of British doctors who received payments from the pharmaceutical industry last year remained anonymous -- prompting a call for greater transparency from drugmaker AstraZeneca Plc.

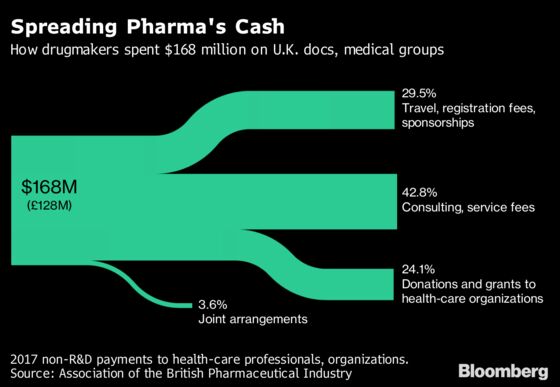

About 128 million pounds ($169 million) flowed to medical professionals or organizations in consulting fees, travel expenses, donations and other items, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry said Friday. Disclosing which doctors got them is tricky due to data-privacy laws, leaving Astra unable to name the recipients of most of the money. Rival GlaxoSmithKline Plc said it could name them all.

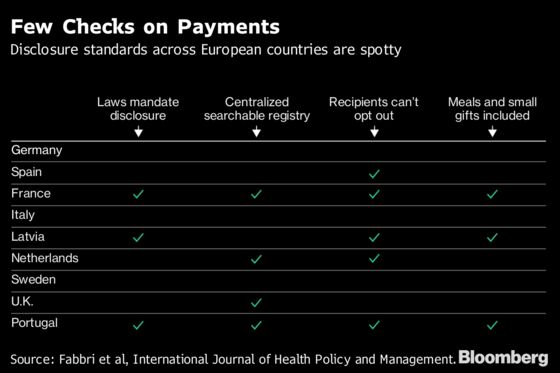

Gaps in reporting have drawn increased scrutiny across Europe. Countries such as France and Portugal have moved to shed more light on pharma companies’ financial ties to doctors, which have been shown to sway prescribing habits. Health-care advocates are pushing for a system like that in the U.S., where legislation requires companies to fully divulge the relationships with medical practitioners.

“This is something that should be regulated, rather than leaving it up to companies,” said Ancel.la Santos, senior policy adviser at Health Action International, an Amsterdam-based nonprofit that contributed to a transparency analysis in March. “It’s in the public interest.”

Unlike some countries that mandate disclosure, the U.K., along with Germany, Italy, Spain and Sweden, depends on the industry to regulate companies, according to the study by Santos and researchers at groups including the University of Sydney and Lund University.

In the U.K. trade group’s report, only half of medical professionals in the country were named, compared with about two-thirds the prior year, a decrease attributed to Europe’s new data protection rules. The trend may reverse as companies adjust to the regulation, according to the ABPI, which said it’s pushing for 100 percent disclosure. A far bigger chunk of pharma payments -- 371 million pounds -- went to research and development.

Astra, the British drugmaker, said it made payments of 2.7 million pounds to professionals in the U.K. last year that require consent to comply with the new General Data Protection Regulation. About three quarters of that money went to unnamed individuals. The company said it’s committed to increasing its disclosure rate by working with the medical community. By contrast, Glaxo said it was able to account for 100 percent of its payments.

Pharma groups say there’s no need for more regulation. Doctors provide crucial insights on new medicines, often while collaborating with companies on clinical research, and they should be paid for their time, according to the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Payments to U.K. physicians to attend events mean the state-funded health system doesn’t need to pick up the cost, the group said.

“We don’t develop medicines on our own,” said Mike Thompson, chief executive officer of the U.K. pharma group. “We can’t do it without the advice of leading clinicians.”

Member companies are now required to disclose payments, though privacy laws in some nations allow doctors not to have their names publicly reported. More pharma companies are making payments only to U.K. doctors who reveal their names, said Alan Boyd, who leads work on conflicts for the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, a standards-setting group that supports voluntary disclosure.

But physicians who get the most are among the most likely to stay anonymous, Santos said. Mental Health Europe, an advocacy group in Brussels, said it’s concerned payments to doctors may influence their use of antidepressants, pointing to research in 2016 highlighting increased youth prescriptions in five countries.

Allowing doctors to opt out “undermines the whole idea of transparency,” said Shai Mulinari, a Lund University researcher in Sweden.

In the U.S., an analysis of government data published this year showed that physicians who accept free meals from opioid manufacturers are more likely to prescribe the addictive painkillers that have been linked to thousands of annual deaths.

Concerns about conflicts were heightened by a junket to Milan that Astellas Pharma Inc. arranged for more than 100 clinicians in 2014. A year later, an oversight body established by the British pharma industry group found the Japanese company violated ethical standards by paying doctors to attend the meeting, where the company’s prostate cancer treatment was promoted. The Japanese company said in an email it’s committed to ensuring compliance.

While Astellas’s giveaway was reported by an anonymous health professional, other such perks may go unseen. It’s not just trips to Greek islands or Alpine ski resorts that raise concerns; payments to cover costs of attending legitimate conferences and deliver lectures may also raise the risk of conflicts and should be monitored, said Ben Goldacre, an Oxford University researcher, science writer and author who has been critical of the industry.

Goldacre, who runs Oxford’s Evidence-Based Medicine DataLab, and his colleagues filed Freedom of Information requests in 2016 with National Health Service administrative units, asking for their data on potential conflicts. Their findings, published earlier this year, revealed that few of the registers included the names of donors, recipients and cash amounts.

“Information on conflicts of interest is poorly collected, poorly managed and poorly disclosed,” the authors wrote in the BMJ Open journal.

Clear Rules

The study began before the NHS issued new guidelines last year requiring medical officials to declare payments that could create conflicts. Goldacre said the measure doesn’t go far enough or bring the data together on the national level. The health service didn’t respond to a request for comment.

U.S. lawmakers moved to require more disclosure after a congressional investigation in 2008 found some Harvard doctors advocated prescribing psychiatric drugs for children while receiving millions of dollars from their manufacturers. In 2013, a government database called Open Payments began publishing detailed annual reports on how much drugmakers give to doctors.

“There are numerous inefficiencies in the way that America does health care, but there’s one thing which I think America historically and consistently is pretty good at -- that’s transparency,” Goldacre said. “Clear rules are the only things that change behavior.”

To contact the reporter on this story: James Paton in London at jpaton4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Eric Pfanner at epfanner1@bloomberg.net, John Lauerman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.