Hedge-Fund Star Sundheim Lures Piles of Cash on His Own Terms

Hedge-Fund Star Sundheim Lures Piles of Cash on His Own Terms

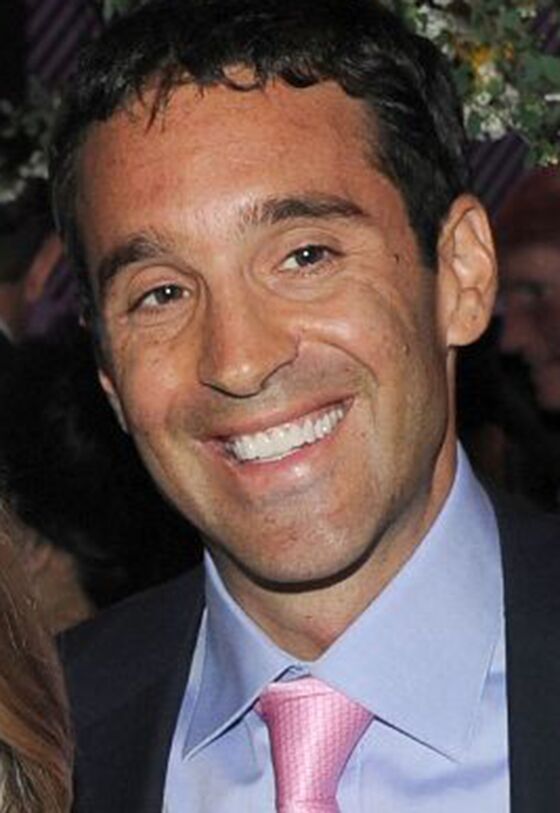

(Bloomberg) -- For Dan Sundheim, who starts trading outside capital at his new hedge fund in mid-July, it might as well be 2007.

That’s when hedge fund managers dominated Wall Street. They could charge high fees, impose long lock-ups on capital and afford to be discerning about which investors they allowed into their funds. Then came the financial crisis and a decade of low returns and client defections. Most startups barely raised any money.

Sundheim, who until last year was chief investment officer at Viking Global Investors, will be at the helm of one of the biggest hedge fund launches of 2018 when he opens his D1 Capital Partners to outside investors on July 16, according to people familiar with the matter. It’s got some old-school conditions attached -- everything from hefty commitments in private equity to an extended timetable for redeeming money. Even with these demands, he’s capping the stock fund at $4 billion and is on track to raise that sum, rare in an industry where clients have gotten used to calling the shots.

Sundheim, 41, is benefiting in part from poor performance at some established multi-billion-dollar firms. While many pension funds and other institutions have given up on hedge funds after years of disappointing results, a core group of investors remain hopeful that there are still a few managers who can make money. The ones with the strongest pedigree, they reckon, might have the best shot, even if they’ve never run their own firm. That helps explain why Michael Gelband, the former heir apparent at Millennium Management -- a steady money maker -- was able to raise a record $8 billion this year for his new firm.

Viking, founded by Andreas Halvorsen, is one of the largest and best-performing equity hedge funds. Sundheim worked for Halvorsen for 15 years and spent seven years as chief investment officer, at the end running almost half of the firm’s $30 billion in assets. Viking has posted annualized returns of more than 15 percent since starting in 1999, according to an investor letter seen by Bloomberg. It’s biggest losing year was a 4 percent drop in 2016.

Fund Terms

Sundheim will start D1 with commitments of $3 billion, according to people familiar with the matter. The remainder is earmarked for Viking investors, who he can begin soliciting on July 1 under an agreement with his former employer, the people said. He won’t oversee all of the money on day one, instead choosing to call the capital from investors as opportunities arise.

While most hedge funds are willing to take any investors who want to give them money, Sundheim did extra due diligence on potential clients, calling industry contacts to figure out which would be the best long-term partners, one of the people said.

D1 is limiting individual client allocations to $200 million, to ensure that no one investor dominates the fund. That condition has deterred some big institutions that prefer to write larger checks. Clients also had to agree that at least 15 percent of their capital can be invested in private companies. Those opting for a higher term -- where 35 percent can go into private transactions -- were given priority to invest in the fund, the people said. If clients want to leave, it will take them two years to get their money out (and the portion in private investments would probably stay in the fund even longer).

A spokesman for D1 Capital declined to comment.

Private Stakes

Sundheim, who has been managing his own money this year, has already taken non-controlling stakes in later-stage private logistics, consumer products and media companies, which will be rolled into the fund, one of the people said.

At Viking, Sundheim and Halvorsen jointly approved private deals that went into a fund that invests in both public and private companies. Sundheim joined Viking in 2002 as an analyst, and three years later was managing his own portfolio. He became co-CIO in 2010 and in 2014 took sole responsibility for that job. During that time until he left in June 2017, the fund annualized at about 7 percent.

Sundheim quit after Halvorsen refused to give him the flexible investment mandate he was seeking. As he walked out the door, Viking gave investors back about $8 billion of capital Sunheim had been running.

To contact the reporter on this story: Hema Parmar in New York at hparmar6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Margaret Collins at mcollins45@bloomberg.net, Katherine Burton

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.