Detroit Went Green and Accidentally Got Faster

The unintentional byproduct of auto efficiency: speed.

(Bloomberg) -- Sometime in the next year or so, the U.S. auto industry will cross a once-unimaginable threshold: Average horsepower for the entire fleet will reach 300. (At the moment, it is tuned up to 296.)

It is an absurd number—the stuff of drag-racing dreams. It’s also, almost entirely, a happy accident. The engineers tuning up the industry’s average sedans and dad-jeans SUVs have spent the past decade trying to lower emissions; speed was an unintended byproduct.

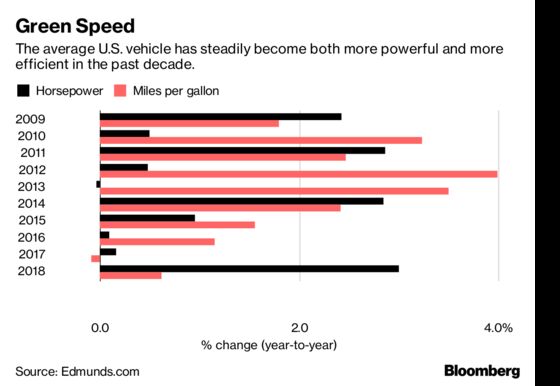

The average miles per gallon for the American fleet has climbed by 24 percent since 2008, according to data analysis by Edmunds.com. Those cars posted a 14 percent boost in power over the same period. In the past year alone, that number jumped by 3 percent.

“We’re in the golden age of horsepower,” said Ivan Drury, senior manager of data strategy at Edmunds. “The only thing I’m nostalgic about—that I know is going to die—is the manual transmission.”

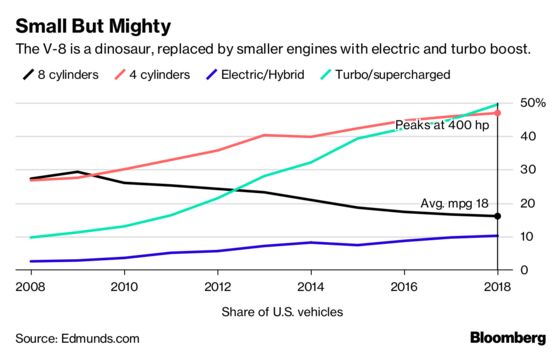

As global regulators progressively tightened emissions standards, automakers were forced to do more with less. They built a mountain of relatively small, super-efficient four-cylinder engines to swap out hulking, thirsty V-8s. At the same time, they increasingly boosted those furious little powerplants with turbochargers and electric motors. These modern engines run like a pack of Australian shepherds—efficient, quiet and even drowsy, until something needs to be chased.

“You can get the best of both worlds,” Drury said. “If you really want it, the power is there.”

Volvo is the best example of this modern approach to power. The Swedish automaker, owned by China’s Geely Holding Group, fits most of its vehicles with the same four-cylinder engine and then tweaks it slightly, depending on the model. It’s the internal-combustion version of an Ikea shelf: simple, pragmatic and abundantly hackable. In its most docile form, the tidy engine makes 260 horsepower, but when fitted with a turbocharger, a supercharger and a pair of electric motors, Volvo increases the output to 400 horsepower.

On the brand’s XC60, that angry engineering equation makes for Porsche-style speed in an SUV designed for soccer practice carpools. The rig will even go 18 miles solely on its electric motors. Not surprisingly, Volvo plans to put the package in almost all of its seven models.

Half of all U.S. vehicles now have a turbo or supercharger, up from 27 percent a decade ago. The share of cars and trucks with an electric motor climbed from 2.5 percent to 10 percent in that time. Big, thirsty V-8 engines are fading like the dinosaurs they run on; only 16 percent of U.S. vehicles available this year come with one.

Smaller engines are even finding their way into the iconic ponies of the past. Ford Motor Co.’s Mustang comes kitted with a four-cylinder that is less than half the size of the car’s traditional V-8. The Ford executive who gave this strategy a green light is both courageous and prescient. To the car nuts who make up the Mustang ranks, this would have been seen as sacrilege just a few years ago, said Bill Visnic, editorial director at the Society of Automotive Engineers. But car buyers no longer pay much attention to the physical size of what’s under the hood. Generally, they look for horsepower and mileage.

“There’s an old saying: ‘There’s no replacement for displacement,’” Visnic said. “Well, that’s finally been dispelled for most people.”

Big rigs are even getting the tiny engine treatment. General Motors Co. recently said it would offer a four-cylinder in the 2019 version of its Chevrolet Silverado. The truck will be more powerful than it was five years ago, when it was mated to a V-8.

“Think about that—a full-sized pickup,” Visnic said. “Once you jump that shark, everything is up for grabs.”

The Chevrolet announcement was a particular coup for BorgWarner, the Michigan-based company supplying its turbo. In recent years, that chunk of its business has grown at an annual rate of more than 11.5 percent, according to Hermann Breitbach, vice president of engineering for the group. What’s next? A wave of turbo-chargers bolted to engines with three cylinders, rather than four. “It’s kind of a logical trend,” Breitbach said.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.