(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It would be a stroke of luck for any other country’s government: On the day it announces a major retirement age increase and a tax hike, the national soccer team wins 5:0 in a World Cup game. But for Russian President Vladimir Putin, Russia’s victory over Saudi Arabia on Thursday was just a cherry on the cake. There would have been no protests against the unpopular moves, anyway.

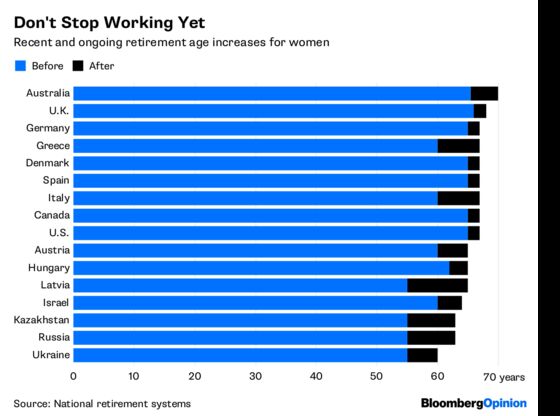

The main reason is that the more important of the two moves, the retirement age increase, was even harder to avoid in Russia than in most other countries. Population aging is a global phenomenon, and dozens of nations are telling citizens they’ll have to retire later than their parents — which makes sense, because people also live longer and their working lives can stretch. The retirement age hikes are steeper in former communist countries which once prided themselves on their social safety nets.

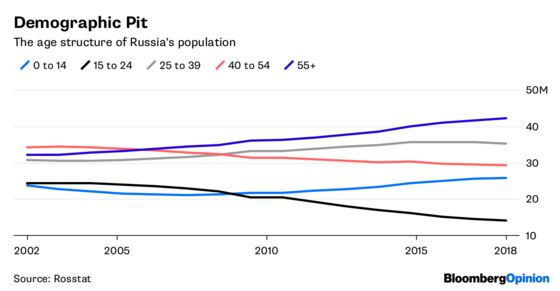

Russia, however, is among the worst-squeezed. In addition to trends that are normal for the rest of the industrialized and post-industrial world, it also faced a particularly long and rough transition from communism in the 1990s. Reforms at that time were fitful and often botched, and the resulting uncertainty caused families to put off or swear off having children. That tendency was reversed during the oil boom of the late 2000s through the early 2010s. But it did lasting damage.

The 15-to-24 age group — people born in the 1990s and early 2000s — is unusually small today compared Russia’s “normal” age structure. As older Russians retire, fewer younger people than ever before come into the workforce. The demographic problem is smoothed slightly by immigration, but it’ll keep dragging Russia down for decades: This lapsed generation will, naturally, have fewer children.

That’s not the only aspect that worries Russian policy makers about the country’s Generation Y. “Despite the relatively high savings activity of Russian youth,” the central bank wrote in a recent report, “Most of it leans toward investing available funds in quality experiences, which is not always a future-oriented motivation. Besides, a desire to control one’s own destiny lowers the tolerance toward participating in collective programs. In the medium term, that can undermine the stability of the existing pension system model, based on intergenerational transfers.”

In other words, Russia’s lost generation — the one that, in the last few years, has shown the greatest willingness to protest against the Putin regime — is also a multi-pronged threat to the pension system, which, in addition to citizens’ obligatory contributions, now absorbs about 2.5 percent of the country’s gross domestic product in subsidies from the federal budget. That means their parents —people born in the 1960s and 1970s — will have to pick up the slack by extending their working lives. After a gradual retirement age increase from the current 60 for men and 55 for women, men born in 1963 will be the first to retire at 65 and women born in 1971 will be the first to stop working at 63. The retirement age for most French and German workers is 67.

A Russian government economic institute has calculated that, with this shift, the number of retirees will drop to some 35 million from the current 40 million by 2035 instead of increasing to some 42.5 million. The budget transfers will more or less peter out. The demographic bomb would be defused, and Russian pensioners will continue receiving roughly a third of the average salary rather than an ever-dwindling amount.

This makes perfect economic sense on paper, though in real life, the retirement age increase may result in higher unemployment, not in higher late-life activity. Russia is a country of widespread age discrimination. A survey for a Higher School of Economics paper published in 2011 showed that 98 percent of retirement-age people in Moscow felt discriminated against when looking for work. Russia’s capitalist economy has a defiantly ageist culture that cannot be changed by decree.

Putin, in any case, will likely not be in the Kremlin long enough to find out whether or not the retirement age increase works as intended. His decision to put it off until being re-enthroned for another six years was likely caused by instinctive caution rather than any rational fear of losing the election or facing protests.

The other unpopular measure drowned out of public consciousness by Team Russia’s unexpected scoring fest will have more immediate consequences. The hike in the value-added tax to 20 percent from 18 percent reverses the cut that Putin himself made in 2004. The increase in consumption tax is meant to give the government some $32 billion in extra revenues until the end of Putin’s fourth presidential term in 2024. It needs the money for health and infrastructure, two areas Putin has promised to prioritize. But before the extra spending kicks in (its effect tempered by the usual glaring inefficiency of Russian government investment), the tax increase will boost inflation, forcing the Central Bank to reconsider further rate cuts and potentially stunting private investment activity.

It’s probably still less dangerous than other tax proposals that Putin has discarded, such as the replacement of Russia’s 13 percent flat income tax with a progressive one. The Russian leader figured it would only increase tax evasion, and it probably would. But even the less dangerous decision to hike the VAT instead promises to continue the general trend toward the displacement of private investment with government funding, which feeds one of the world’s most corrupt economic systems and damps Russia’s growth prospects.

If Russia is doing somewhat better at economic diversification (and soccer) than Saudi Arabia, the government’s ever-strengthening role in the economy will continue to hold the country back throughout Putin’s current term. And the lost generation Y, luckily for Putin and unluckily for the nation, will be too small to change anything.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.