Here’s the Poster Child for Silicon Valley Excess

Here’s the Poster Child for Silicon Valley Excess

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- You most likely haven't heard of Domo Inc., but the Utah-based software startup has received a healthy amount of attention in Silicon Valley largely because it has a charismatic founder who made tech investors (and himself) rich once before.

You should know Domo, though, because it has emerged as the poster child for what can go wrong when startup founders have too much power and not enough guardrails.

Domo on Friday filed for an initial public offering, which is usually a celebratory milestone for a young company. It's not for Domo. The company warned in the IPO filing that it must go public or find other sources of cash by August, or else it must start slashing costs. Josh James, the founder and CEO, has 40 times the voting power of other stockholders, which is notably high even by the standards of founder-empowered tech companies. And as a kicker, James has found several ways to use the company as a personal piggy bank.

It’s a mess. I have no idea how an experienced technology entrepreneur like James, combined with an array of seasoned Domo investors and board members, allowed the company to get this way. It's easy to imagine that Domo and its backers have deferred too much to James to run the company how he wished, and the result was a company in precarious financial position that nevertheless has found several ways to enrich James personally.

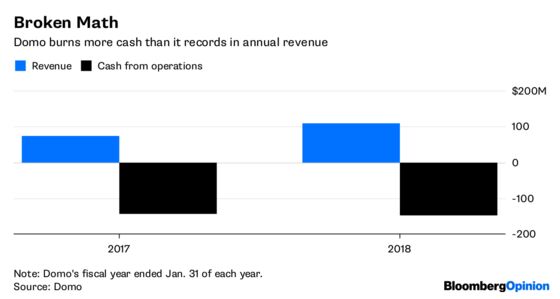

I'll start with the precarious financial position. Domo had about $72 million in cash on its books at the end of April, had tapped out a $100 million credit line, and its operations burned through $37 million in cash in the most recent quarter. That is not much of a cash cushion, and the company is raising the alarm. "If other equity or debt financing is not available by August 2018, management will then begin to implement plans to significantly reduce operating expenses," Domo said in its IPO document.

Of course, Domo is far from the only company that has burned through cash and found itself in need of a quick infusion. But it's clearly not ideal to go to market needing money so badly. Desperation is not a good look for a company trying to pitch itself to public investors.

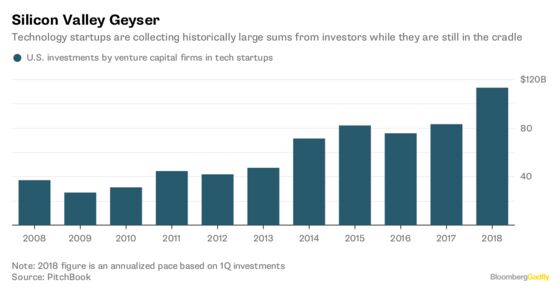

It’s not clear why James and Domo's investors allowed the company to get into a position where it may either need to go public or hack itself to bits. Some context may help, though. Domo is emblematic of the post-2010, easy money and "founder friendly" era of technology startups.

James made a name for himself by co-founding an web analytics startup called Omniture in the relatively early days of the internet and selling it for $1.8 billion. He said he started Domo to fix a problem he saw at Omniture: It was too hard for managers to access basic metrics for their companies in a timely fashion. That's what he designed Domo's software to do.

It was a good professional story, and James leveraged it and his success with Omniture to generate publicity and hundreds of millions of dollars in investments. James developed a reputation as something of a savant at raising capital, and he won backing from several top-flight tech investors.

Along the way, James found ways to make money even while his company was bleeding cash. In the IPO filing, Domo said it had paid $1.6 million in the last two fiscal years combined to lease a private aircraft owned by James. (Domo said it uses the plane for "our businesses and on as-needed basis.”) That's not money that makes or breaks a company, and it's not unusual for public companies to pay to lease jets owned by their executives. At a young, cash-burning company, though, such an arrangement feels gratuitous.

Domo also disclosed that it paid $600,000 combined over two years for catering from a restaurant owned by James and his brother. The menu does look delicious, but there must be caterers in American Fork, Utah, that aren’t owned by the boss. Domo also paid about $200,000 more than a year ago for furnishings from an interior design company that was part-owned by James and at which a different brother is an executive.

Again, those are not huge sums, and James has a small fortune tied up in his company's stock. Still, the appearance is ugly. James's company is fighting to stay whole, he is wealthy enough to afford a private jet, and yet Domo keeps finding ways to throw business his way.

Silicon Valley has now produced multiple versions of cautionary tales. There are those like Uber, with entitled founders who made many mistakes and investors who exercised too little oversight, but their companies still turned out mostly fine (so far). Then there are the entitled founders like Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos, whose board was asleep at the switch and whose company definitely did not turn out fine.

It's clear that James's company got out far ahead of its skis and is apparently turning to the stock market as a financing source of last resort. Domo seemed to have everything going for it, including an experienced and savvy founder and smart investors. It’s unfortunate those qualities seemed to create the conditions that have nearly broken the company.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.