Diamonds Aren't Forever

Who wants to seal an engagement with something whose price makes it feel little better than costume jewellery?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For the inheritor of a century-old oligopoly that once held the world diamond trade in its fist, De Beers Group Chief Executive Officer Bruce Cleaver has an odd approach to marketing.

“Lab-grown are not special, they’re not real, they’re not unique. You can make exactly the same one again and again,” he told Thomas Biesheuvel of Bloomberg News Tuesday, after announcing that the Anglo American Plc-controlled company would start selling synthetic gem diamonds for as little as $800 a carat from September.

Disparaging your product isn’t a strategy that’s taught in many business schools, but it’s a clue to what’s really going on here. The product Cleaver is worried about isn’t synthetic diamonds, but the natural stuff it digs out of extinct volcanoes in Africa.

De Beers was founded in the midst of a potential catastrophe for the diamond market. The gems, once almost impossibly rare recoveries from a handful of rivers in India and Brazil, saw a sudden jump in supply in the 1870s and 1880s after the discovery of the first mine deposits near Kimberley in South Africa.

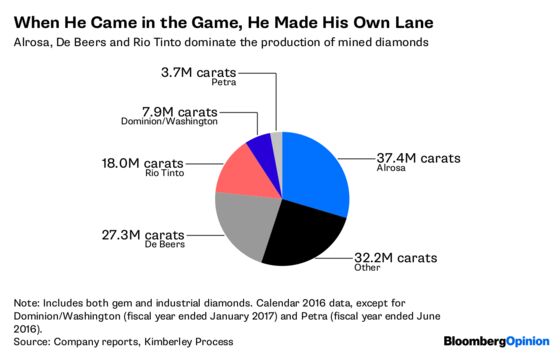

The risk in such a situation was that a once-prized rarity might turn into a cheap commodity. De Beers’s solution was to build a monopoly that controlled the world’s supply in one form or another from 1888 until 2006, when it settled an antitrust suit brought by the European Union by agreeing to stop buying diamonds from its largest rival, Russia’s Alrosa PJSC.

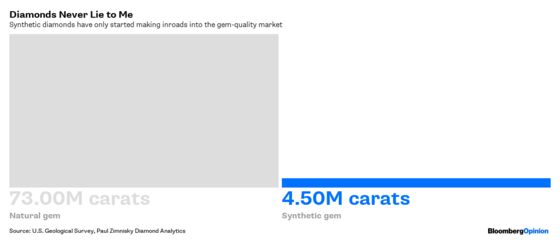

The rising sophistication of lab-grown diamonds threatens a potential repeat of the Kimberley supply surge. At present, they’re a tiny portion of the total — somewhere between 4 and 5 million carats, according to Paul Zimnisky, a New York-based analyst of the market, versus about 73 million carats of gem-quality diamonds dug from the ground in 2017.

It’s not easy making diamonds of gem quality in a lab, so the handful of producers that do it generally market them as a direct and even superior substitute to the natural stuff.

Take Diamond Foundry Inc., a San Francisco-based manufacturer that boasts endorsements and investment from Leonardo DiCaprio, star of the 2006 film “Blood Diamond.” If you ignore the long sections attacking the environmental, social and investment credentials of natural diamonds, the language and imagery on its website could be cut and pasted direct from a De Beers brochure.

That positioning could pose a problem for mined gems. Lab-grown diamonds have reached a level where even trained gemologists are unable to tell the two apart without highly specialized equipment. In a worst-case scenario, rising acceptance and output of lab-grown diamonds could see them become price setters, undermining the economics of the entire mined industry.

De Beers’s move is best understood as an attempt to kill that nascent sector before it gets any bigger.

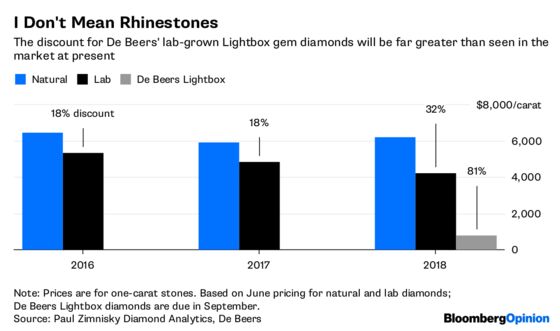

By pricing its Lightbox Jewelry-branded gems as low as $800 a carat — an 81 percent discount to the price of natural gems, compared to the 32 percent discounts existing synthetic gems are fetching — it’s sending an unmistakable signal that artificial diamonds should be considered little better than rhinestones.

“It’s kind of like dropping the atom bomb on the lab-created industry,” said Zimnisky. “This isn’t about trying to take market share in the lab-created industry, it’s about trying to steer the identity of the industry and prevent it cannibalizing natural diamonds.”

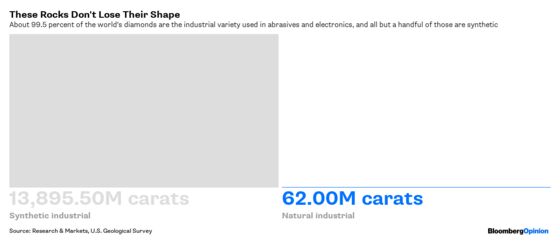

That seems almost too audacious a strategy to work — and when you consider the scale of the synthetic diamond industry, which already accounts for about 99 percent of global supply (the vast majority of it for industrial diamonds that are used as abrasives and in electronics), it feels like a David and Goliath battle that the miners are destined to lose.

Still, De Beers’s bet is that people won’t want to seal an engagement deal with something whose price makes it feel little better than costume jewelry. If there’s one lesson from this company’s history, it’s that a rock-solid luxury marketing strategy combined with a oligopolistic market position can overwhelm any ideas of what “rational pricing” should be.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Katrina Nicholas at knicholas2@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.