Why Is It So Hard for Corporations to Say They’re Sorry?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Welcome to Open Thread, a moderated discussion with Bloomberg Opinion columnists. Today’s question: What makes for a good corporate apology?

Faye Flam: To make a sincere and satisfying public apology, corporate leaders need to include a reflection on what they’ve learned. This isn’t my original idea but one I repurposed from C.K. Gunsalus, director of the National Center for Professional & Research Ethics at the University of Illinois. She breaks down a good apology into “the four Rs”: remorse (“I’m sorry”), responsibility (“I did it”), rehabilitation (“Here’s what I learned and how I’m going to do better”) and recompense (“Here’s how I’ll make it up to you”).

In looking at various public apologies, I noticed that people generally get stuck after the first two Rs. Corporations can take care of the last R by offering money. But public apologies tend to gloss over the rehabilitation part. That helps explains why Mark Zuckerberg’s apology last month for the breach of private data at Facebook felt so unsatisfying. What did he learn? He never says.

By the same token, we the public would like to know what corporate leaders at Starbucks, which will close some 8,000 company-owned stores this afternoon for racial-bias training for employees, learned from the incident in which two black men were arrested last month at one of its shops in Philadelphia. If they didn’t learn anything, it’s hard to see how they could truly take responsibility or improve things in the future.

Justin Fox: The classic case of how a corporation should deal with something gone terribly wrong is Johnson & Johnson’s 1982 Tylenol recall. Seven people in the Chicago area had died after taking Extra Strength Tylenol capsules laced with cyanide. The company figured out quickly that it was not directly responsible — someone had tampered with the bottles on store shelves — so remorse wasn’t really in order. But it took responsibility immediately, announcing a product recall that cost $100 million, and moved on quickly to rehabilitation via new tamper-resistant bottles.

I think part of the issue with the unsatisfactory nature of a lot of corporate apologies is that true rehabilitation is often a lot harder than that. Tylenol itself remained a safe and useful product. What if what you’re selling is the problem? Mark Zuckerberg can apologize for a data breach, and do it poorly. But if rehabilitation involves ditching Facebook’s super-lucrative business model of exploiting and manipulating users to sell ads, one can see why he wouldn’t want to go there. And, clearly, sometimes just brazening things out and not admitting to any errors at all can work pretty well. Just ask the guy in the White House.

Faye: Justin, your Tylenol example is a good one, since there were many factors that led to the Starbucks incident, not all of which were caused by company management. Still, as a potential future customer I wanted to know which aspects of the incident the CEO did feel responsible for. Was there a problem with training managers? He mentioned differences in local policies but it wasn’t clear what these entailed.

Justin: I feel like Starbucks is always going to have tension between being this "third place" where people go to hang out and a business that sells expensive coffee. So it’s a little hard to tell what exactly it needs to apologize for and rehabilitate. Yeah, the people at that Starbucks in Philly didn’t handle things well, but the right answer can’t be that anyone can hang out at Starbucks all day.

Faye: Agreed! That looks like the wrong form of rehabilitation. The apology seemed to be claiming responsibility for the whole mess and promising to fix it. It’s pretty hard for a coffee chain to fix racism. However, there might have been some problems in training managers to avoid discrimination, so it would have been nice to see a realistic accounting of the situation and some explanation for how sensitivity training will help avoid this kind of thing in the future.

Justin: To use your four Rs, Faye: Starbucks has done Remorse and Recompense just fine. But I’m fuzzy on the Responsibility and not sure they’re ever really going to get Rehabilitation right.

Faye: Yes, Starbucks is being very vague about the responsibility part — claiming responsibility for everything that went wrong that day, rather than telling us what part of the mess they feel responsible for. The 4 Rs kind of fit together so if there’s a problem with one, it’s hard to make the others come across as realistic or sincere.

Justin: Howard Schultz basically feels responsible for many of the world’s ills. Which is sort of endearing but he tends to be pretty tone deaf in his proposed remedies. Like when he wanted baristas to write “Race Together” on people’s coffee cups after Ferguson. I do get this duck-for-cover reflex when Schultz goes on one of these campaigns, but I think his heart is in the right place and I don’t think he's doing any harm.

Faye: When I looked into apologies for a recent column, it came up in the context of leadership. Ultimately, people accept apologies from leaders. And so we still want to know if there was some way the company policy contributed to the problem. And for the rehabilitation part, we want to know what the leader of the company learned.

As for that $5 Caramel Cocoa Cluster Frappucino that this guy mentions: The price, the carbs, the caffeine that will keep you awake for three days ... That’s also a problem — not everyone can drink this stuff and survive.

Justin: Well, there is that. But then I’m waiting on the apology campaign from the CEOs of Coke and Pepsi. I think there are a bunch of businesses that at some point figure out that their main products do more ill than good, and it’s really interesting to watch how they handle it.

Can we talk about Zuck? Facebook is a corporation that actually does bear some responsibility for many of the world’s ills.

Faye: A linguist analyzing Zuck’s apology noticed that his statement amounted to bragging about how powerful he was, then apologizing for “what happened.”

Justin: Zeynep Tufekci had an an essay recently describing Zuckerberg’s 14-year history of apologizing for stuff and then going ahead and continuing to do similar things.

Faye: Zuckerberg’s apologies lack everything except for the expression of remorse. There’s no realistic sense of responsibility, let alone rehabilitation. He never tells us what he’s learned.

Justin: And here’s the thing: Zuckerberg is a super smart, super capable CEO. Despite having no background or training in it, he’s become this great manager who hires amazing people and gets them to stick around when they could easily be CEOs elsewhere. Zuckerberg could undoubtedly craft a convincing apology if he were really willing to change how Facebook does business. But he’s not willing to touch any of the Rs beyond a sort of vague remorse.

Faye: It’s good to remember that. There’s no training for his position. Someone could have helped him think through the public apology for the data scandal. There was a more focused way he could have apologized for not being more straightforward about the ways data would be used. The public outrage that followed these scandals isn’t always rational, but it is kind of predictable.

Justin: Right. If Zuckerberg really wanted to do an all-four-Rs apology, he would hire an apology trainer and do a bang-up job. He just doesn’t.

Faye: Facebook’s scandal of a few years ago, where it was manipulating people’s news feeds to affect their emotions, was really not as awful as it was made to sound. Nobody was harmed. I think there’s some good sense in apologizing only for what was your fault, and not for all the wrongs in the world.

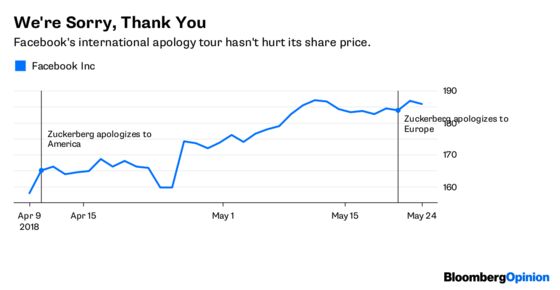

Justin: Of these two current corporate apology campaigns, I would say that Facebook’s is working better. It’s clearer what the goal is: to stall regulators and lawmakers who might eventually destroy the company’s business model. It’s just a delaying tactic, and it’s definitely working, in the U.S., at least.

Faye: I guess it really depends on whether effective is defined as good for the company, or good for the customers and the public at large. The Starbucks apology and new sensitivity training might make customers feel better, and therefore allow people who like the place to go there without feeling like they are contributing to racism. The Facebook apology is more complicated. It didn’t come across well to the viewing public, but then, as Justin says, it’s more complicated to fix the problem and preserve the business model.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Michael Newman at mnewman43@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.