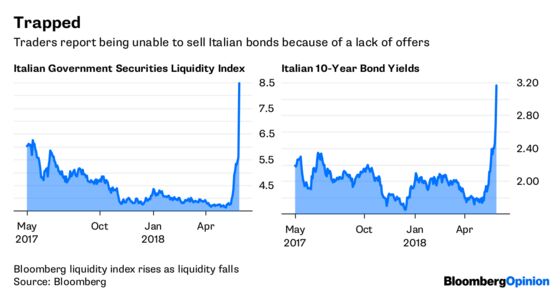

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As if the collapse in Italy's government bond market — the fourth-largest in the world, with more than $2.2 trillion outstanding— wasn't enough to shock investors, a related development should cause just as much concern: a lack of liquidity.

At the same time that prices of Italians bonds plummeted on concern the nation may be gearing up to quit the euro zone (hence, the “Quitaly” moniker), causing their yields to spike, some of the biggest investors in the world were complaining about the inability to get out of their positions. In fact, bond dealers refused to offer quotes for most of Italy's market and parts of Spain's, Bloomberg News's John Ainger reported. At one point, the Bloomberg Italy Government Securities Liquidity, which rises when liquidity diminishes, surged the most since 2007. The issue of liquidity, or lack of, has been a concern since the financial crisis as dealers cut back on thousands of jobs to comply with new rules and regulations. The fear has always been that in a real crisis, like, for example, Italy deciding to leave the euro zone, a built-in mechanism wouldn’t exist to take the other side of huge sell orders, exacerbating a crisis. But it's times like now that regulators should want their banks to have big balance sheets. In that sense, it's questionable whether the global finance system has really been made safer.

”The supply-demand imbalance is gigantic and the liquidity is incredibly poor,” Scott Thiel, the deputy chief investment officer for fixed income at Bond giant BlackRock Inc., told Ainger in an interview. “It would be impossible to transact in any appreciable size." Perhaps the silver lining is that the moves overstate the magnitude of the crisis facing Italy and the euro zone. "The market has divorced itself from the fundamental story,” Thiel said.

WHERE'S THE BOTTOM?

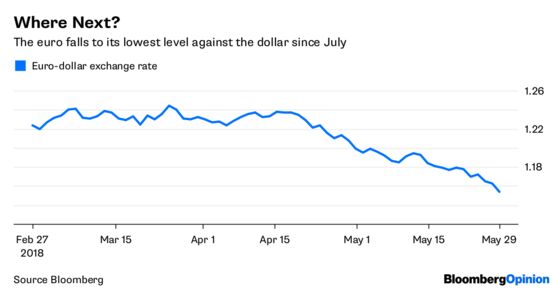

The first question traders and investors were asking Tuesday was: How bad could it get in Italy? Judging by past trading patterns, the answer was a lot worse. The 2010-2012 euro crisis pulled the common currency down by as much as 25 percent, according to Societe Generale market strategist Kit Juckes. By comparison, the euro has dropped only about 10 percent in recent weeks. That means the risk of the euro falling to $1.10 by the end of summer from about $1.15 on Tuesday "is significantly higher" than the possibility of a recovery to $1.20, Juckes wrote in a research note. Although the weaker euro may help support the region’s exporters, it might detract much needed foreign capital. The same holds true of Italian bonds. Even though 10-year yields shot as high as 3.44 percent on Tuesday from about 1.79 percent at the start of May, they reached as high as 7.48 percent in late 2011. And at 2.87 percentage points, the difference in yields between Italian and German bonds compares with the peak of 5.49 percentage points in 2011. "The threat of further rating downgrades hangs over" Italy's bond market, Juckes wrote in the note. Moody's Investors Service said Friday that it might cut Italy's credit rating, which is just two levels above junk, on concern about the new government’s fiscal plans and the risk that some important past measures, such as pension reform, might be reversed.

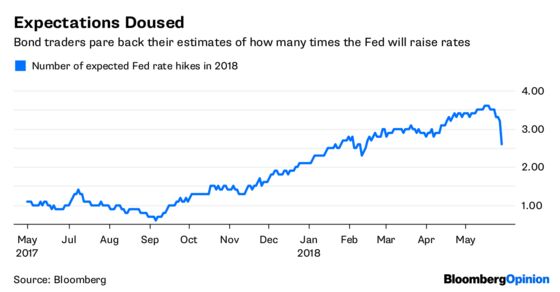

WHITHER THE FED?

Three weeks ago, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell signaled in a speech that the budding turmoil in emerging markets wouldn't alter the central bank’s plans to raise interest rates at least twice more this year. But now, with Italy rocking not only the euro zone but global markets as well, traders are betting the headwinds may become too stiff for the Fed. While a quarter-point increase next month to a range from 1.75 percent to 2 percent is deemed a done deal by the futures market, the expected hikes in September and December are i n doubt. As such, yields on two-year Treasury yields have plummeted, falling as low as 2.31 percent Tuesday from as high as 2.60 percent less than two weeks ago. Stock traders are clearly spooked by the developments in Italy, driving the S&P 500 Index down as much as 1.64 percent on Tuesday and putting it within a whisker of erasing its gains for the year. Banks globally were hit particularly hard, which is never a good sign. The Bloomberg World Banks Index tumbled as much as 2.51 percent, the most since June 2016. “The political situation in Italy is troublesome, and then you get broader concerns about the strength of the euro market in general and that in turn has some people thinking maybe the Fed here in the U.S. slows down on raising rates,” Peter Jankovskis, co-chief investment officer at Oakbrook Investments, told Bloomberg News. “That’s been a big pillar for the financials overall, that rates will continue to rise and their margins will continue to improve because of that.”

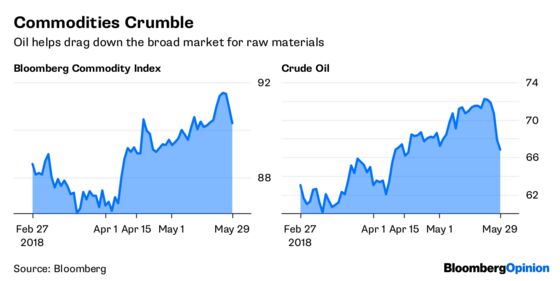

COMMODITIES CRUMBLE

The commodities market wasn't spared, with the Bloomberg Commodity Index stringing together its biggest two-day slide since early March by falling as much as 1.35 percent. Traders clearly think the turmoil in emerging markets and the euro zone will hurt global economic growth and demand for raw materials. The declines were spread out across all commodities, from oil to copper to corn. As usual, oil received most of the attention as crude extended a weeklong rout amid signals from Saudi Arabia and Russia that they will restore some of the production they’ve curbed to drain a global glut. West Texas Intermediate for July delivery dropped $1.15 to settle at $66.73 a barrel on the New York Mercantile Exchange after earlier touching $65.80, the lowest intraday level since April. Oil futures were headed for a fifth consecutive session of declines, the longest such stretch since February, according to Bloomberg News's Jessica Summers. The drop should help lower gasoline prices, which had risen to nearly $3 a gallon in the U.S., the highest in four years. “Clearly, the commentary from Russia and Saudi Arabia popped the bubble,” John Kilduff, a partner at Again Capital LLC, a New York-based hedge fund, told Bloomberg News. Talk of rising output from the world’s top two oil exporters wiped out this month’s rally, which had been fueled by concerns that supplies from Iran and Venezuela will shrink.

TURKISH DELIGHT

Emerging markets took another tumble Tuesday, with the MSCI EM Index dropping as much as 1.32 percent to move deeper into the red for the year and a related index of currencies falling as much as 0.72 percent. If the global economy is poised to slow and demand for commodities, which are a key export of developing-nations, wanes, then financial assets in these markets are going to get penalized. Already, emerging-market economic data is falling below estimates by the greatest degree since 2016, according to Citigroup Inc.'s economic surprise indexes. Worst hit on Tuesday was South Africa. The rand dropped 1.80 percent and its main equities index tumbled 1.62 percent. One surprise on Tuesday was Turkey. Its long-suffering lira appreciated for the second consecutive day on optimism the central bank’s decision to bring clarity to its interest-rate regime signaled that it might be able to fight the currency’s depreciation without pressure from President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The monetary authority said that starting in June its benchmark would be the one-week repurchase rate, which it hadn’t used as its main funding tool since January 2017, according to Bloomberg News's Tugce Ozsoy. “The sell-off has tipped the balance in favor of increased central bank independence,” Per Hammarlund, the chief emerging-market strategist at SEB AB, told Bloomberg News. “A reversal of this stance and increasing political influence over monetary policy is unlikely in the coming months.”

TEA LEAVES

Keep an eye on Canada on Wednesday. That's when the Bank of Canada officials wrap up a meeting on monetary policy. Although the consensus is that the central bank will keep its target interest rate at 1.25 percent, it will be interesting to see whether officials suggest that they think the recent turmoil in emerging markets and Italy, as well as the continuing Nafta talks, will impact the global economy and whether they play down the potential for a rate increase in July. Although the Canada dollar has been supported by the rebound in oil and energy prices, the currency is still down for the year as measured by Bloomberg Correlation-Weighted Indexes. Canadian households are heavily indebted, with mortgages, credit-card obligations and other borrowings having swollen to C$2.1 trillion ($1.6 trillion), levels that as a share of income are easily the highest in the Group of Seven, according to Bloomberg News's Chris Fournier and Erik Hertzberg.

DON'T MISS

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.