$83 a Month for Government Workers May Be Too Much for Nigeria

$83 a Month for Government Workers May Be Too Much for Nigeria

Tope Ajao earns 18,000 naira ($50) a month cleaning floors at Nigeria’s Ministry of Agriculture. She’ll soon start benefiting from a government decision to almost double the minimum wage -- even though it’s not clear her country can afford it.

As small as Ajao’s salary looks, Nigeria will struggle to pay the 368,000 government workers affected by the hike. Already, the finance ministry says it won’t implement the increase until December, even though the agreement was made in April.

And on top of the minimum-wage increase, Africa’s largest oil producer agreed last month to pay rises of between 10.5% and 26% for workers earning just above the minimum. In all, the new wage bill will cost the government 2.84 trillion naira a year, 27% of total spending, but 73% of 2018 income. Meanwhile, lower-than-expected revenue has pushed the national debt up 104% since 2015.

Yet the raises are badly needed: Nigeria surpassed India last year as the country with the most people living in extreme poverty, defined as less than $1.90 a day. Before the hike, wages had been largely unchanged since 2011, even though inflation has been above 10% since 2015.

“30,000 naira is a lot of money for me and my family,” Ajao said as she swept the floor, bending over because her broom was so short. “We already have a plan to use some of the money for business and pay some of our debts.”

The Ajaos still need to economize. Her husband also works, as a driver, but they have taken out loans from cooperatives to pay school fees for their three children and for other household expenses. They live on the outskirts of the capital, Abuja, where makeshift accommodation is cheaper, and Ajao supplements her income by occasionally cleaning homes in the more affluent areas in the city center.

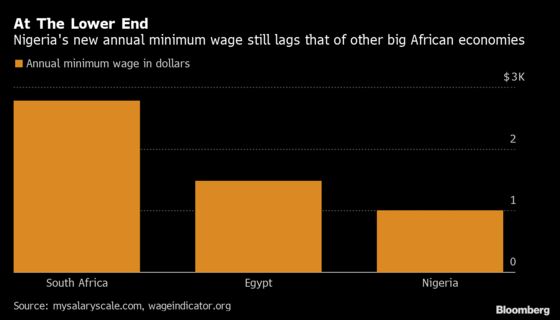

The new annual minimum wage is just a third of the $2,800 pay floor in South Africa, which vies with Nigeria as having the biggest economy on the continent.

Higher costs for the government don’t just include wages, said Finance Minister Zainab Ahmed during a presentation on the 2020 budget. The addition of pension and overhead expenditure will raise total worker related costs to 4.88 trillion naira -- more than half of target revenue for 2020 and 125% of revenue actually collected last year.

Nigeria has missed annual earnings projections every year since 2016, according to the budget office. The government had only collected 58% of its 2019 revenue target as of June, President Muhammadu Buhari said last month. This was due to shortfalls in both oil and non-oil earnings, with the government takings from crude sales 49% below target.

Revenue at 8% of gross domestic product is sub-optimal and “attests to reality of the inadequacy and inefficiency of tax collections,” Ahmed said at an event during the International Monetary Fund and World Bank’s annual meetings in Washington D.C. this month.

Africa’s most populous country has depended on debt financing since 2015 to cover up for the government’s earnings shortfall. Debt as a portion of gross domestic product is at 19%, but debt-service payments consumed 63% of income last year, raising concerns from the IMF about a possible debt crisis. The government is considering increasing the value-added tax and other levies, including petroleum tax and royalties, to boost earnings.

Questions about the affordability of the minimum wage increasingly underscore the urgent need to raise non-oil revenue, said Razia Khan, chief economist for Africa and the Middle East at Standard Chartered Plc.

“The move to increase VAT comes at a necessary time, but broader issues around tax compliance also need to be considered, and even a 7.5% VAT rate is unlikely to be adequate for Nigeria’s needs over time,” Khan said.

The higher wages will boost spending, especially for low-income earners, but is not going to have any significant impact on economic growth, Michael Famoroti, an economist and partner at Stears Business in Lagos, said by phone.

“In real terms, wages are still not catching up with prices,” he said. “Inflation annually is about 10% to 11%, which means that each year, wages need to grow by about 10%.”

Ajao, for her part, doesn’t plan a spending spree when the new wage kicks in. Wearing a multicolored dress under her orange overalls, she shares a workstation with five other women.

“I am really looking forward to the minimum wage,” she said. “It will go a long way in paying our children’s school fees.”

--With assistance from Tope Alake and Rene Vollgraaff.

To contact the reporters on this story: Anthony Osae-Brown in Lagos at aosaebrown2@bloomberg.net;Ruth Olurounbi in Abuja at rolurounbi4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John McCorry at jmccorry@bloomberg.net, Anne Swardson, Paul Richardson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.