What the Year of the Tech Unicorns Means for the Bull Market

Someone knows something about the markets that you don’t.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Psst! Someone knows something about the markets that you don’t.

That’s the vibe on Wall Street these days, at least among those prone to occasional bouts of what could generously be called caution—or not-so-generously called paranoia.

Federal Reserve policymakers see something the rest of us don’t, the thinking goes, and that’s why they have all but canceled interest-rate hikes once planned for 2019. Bond traders obviously know something stock investors are missing, so they’ve inverted the yield curve by pushing yields on 10-year Treasuries below rates on three-month bills in a classic harbinger of a recession.

And will you get a load of this herd of unicorns prancing their way toward initial public offerings? Clearly their bankers have whispered in their ears, alerting them that the grass is high in public markets and now is the time to graze because a drought is coming.

The “Fed knows something” concern is easy enough to dismiss for anyone who has even a cursory familiarity with the central bank’s track record as a fortune-teller. The yield-curve inversion is harder to ignore, given its habit of arriving on the scene before recessions, though a “this time is different” case can be made because of the lingering effects of the central banks’ massive intervention in bond markets following the global financial crisis.

What, then, of this unicorn invasion? It’s a tricky subject. The nickname refers to startups, mostly venture-capital-backed Silicon Valley creatures, that achieve private valuations in excess of $1 billion, whether or not they’ve turned a profit. They were originally called unicorns because their existence once seemed impossible, but these days they’re as common as white-tailed deer on a New Jersey golf course.

The alpha unicorn of this pack is obviously Uber Technologies Inc., the unprofitable taxi app that is expected to come to market next month in an offering that could value the company at as much as $120 billion. Its unprofitable rival Lyft Inc. is getting there first. But the list of expected IPOs goes on and on and on: digital corkboard Pinterest, home-rental site Airbnb, takeout and grocery delivery service Postmates, chat-room operator Slack Technologies, electronic trading platform Tradeweb Markets, virtual conference company Zoom Video Communications. (Even a San Francisco-based innovator of yesteryear, Levi Strauss & Co., made its triumphant return to public markets this month.)

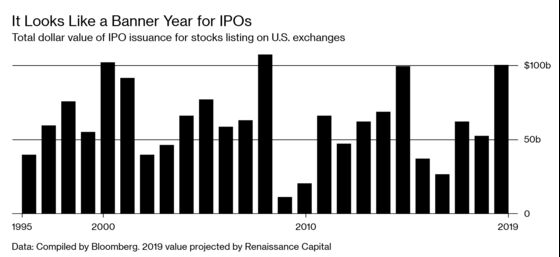

Should these and others make it to the stock exchange, 2019 could prove to be one of the biggest years on record for the amount of money raised in U.S.-listed IPOs. The total will reach $80 billion this year, double the yearly average since 1999, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. predicted in November—an estimate that may prove low. And there’s no arguing that peaks in IPOs have occurred near major tops in the stock market and close to the onset of recessions. Both 1999 and 2007 were unusually strong years for IPOs that were swiftly followed by nasty bear markets in stocks and downturns in the economy.

“I get the point: At market tops, confidence is high and everyone is buying with little concern for price,” says Jim Paulsen, chief investment strategist at the Leuthold Group in Minneapolis. “From a private company standpoint, that sounds like a great time to bring an IPO.” But contrarians beware: Paulsen points out that irrational exuberance doesn’t exactly describe the mood of investors these days. While the S&P 500 is up about 12 percent in 2019, poised for its best quarter in seven years, it has yet to fully recover from a fourth-quarter swoon. “I would argue that, although the market is up this year, it sure seems like cautiousness and pessimism about recession and a bear market is also up this year,” he says.

Regardless of the signal about sentiment that this unicorn stampede is sending, there’s a more practical issue to consider: supply and demand. Can the investor class absorb this much new stock without dumping shares of established companies to raise funds?

Kathleen Smith, a principal at Renaissance Capital LLC, which provides institutional research and exchange-traded funds focused on IPOs, says that this year’s IPO issuance could be more than the market can digest smoothly. “If you look at what it took to have a robust $100 billion-plus IPO market, we don’t have a lot of those dynamics now,” Smith said. “You have the extra issue of, ‘Oh my gosh, look at all this supply.’ ” The overabundance of IPOs, she suggests, could lead to market volatility or simply weigh on the performance of the newly public stocks.

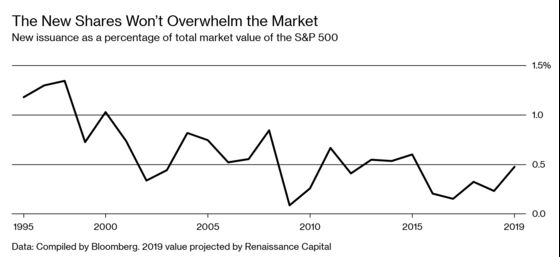

No indicator has a perfect track record. The yield curve’s brief inversion in 1998 sent a false signal, as did a longer episode in the 1960s. If the signal it’s flashing this time is correct, exactly how many months it takes for the recession to arrive is not easily determined by historical precedent. There would likely be a lot of nickels to pick up in front of the steamroller, because the S&P 500 tends to rise in the period between inversion and bull-market top. And when it comes to all those unicorns, even a record year of issuance in pure dollar terms is unlikely to be a record amount in relation to the market’s total size. Nor will it do much to halt the shrinkage of supply in total shares outstanding being caused by corporate buybacks. The last major scare of an IPO overdose was when Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.’s $25 billion stock market debut in 2014 triggered talk of a market top. (Narrator: There was no market top.)

Perhaps the true unicorn is a foolproof signal of when a bull market is over. It doesn’t exist. —With Sarah Ponczek

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Joel Weber at jweber66@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.