The Gazillion-Dollar Standoff Over Two High-Frequency Trading Towers

The hunt for a millionth-of-a-second advantage in the town best known for Wayne’s World is getting heated.

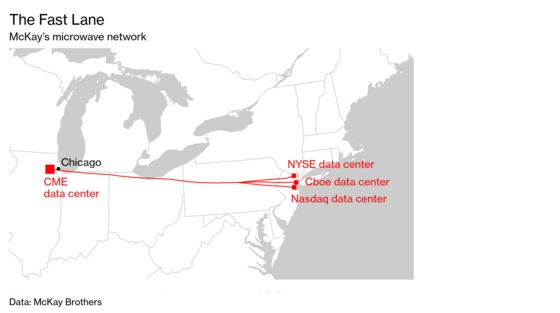

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In a weedy field 35 miles west of Chicago squats a tidy red-brick building with a peaked roof, about the size of a one-car garage. Against the eastern wall, reaching just above the roofline, are poles equipped with small dish antennas that send microwave signals to and gather them from financial markets on the East Coast. At the same time, the site communicates via subterranean cable with an enormous steel-and-glass building across the street. That fortress is home to CME Group Inc., a $63 billion exchange where some of the world’s most vital financial products trade, including derivatives on oil, gold, U.S. Treasuries, and the S&P 500. If you want to be a serious player in global markets, you have little choice but to stash your trading machines here.

The little brick hut in Aurora, Ill., is part of New Line Networks LLC, a joint venture of Chicago’s Jump Trading LLC and Virtu Financial Inc. of New York City, two of the nation’s most successful high-frequency trading firms. In 2016, Jump Trading paid $14 million for the 31-acre plot where the building sits to be close to the CME center.

Not far away, high-frequency trading company DRW Holdings LLC of Chicago, angling to be even a few yards nearer, slapped an antenna on a light pole. Next to that stands yet another pole rigged with antennas, this one owned by McKay Brothers, an Oakland-based company that builds telecommunications networks and leases access to traders.

Up and down adjacent roads, trading companies have erected or rented space on more towers and poles, all of them arrayed with white circular dishes. These companies, too, are seeking to cozy up to the CME data center, trying to shave millionths of a second off trades. They save that time by keeping their data in the air, where it travels at maximum speed, for as long as possible. The closer their dishes to the data center, the shorter their underground connections, the speedier their transmissions.

In a bid to end the gamesmanship, CyrusOne Inc., the Dallas company that owns the CME center, last year erected a 350-foot-tall wireless tower next to the building, closer than any trading firm could otherwise get. The tower was supposed to put everyone on equal footing and make those roadside antennas obsolete by letting all traders have the same very short link to CME. Not coincidentally, the traders would pay rent to CyrusOne—the tower has room for about 35 dishes.

But the CyrusOne tower stands unused, partly because a smaller company, Scientel Solutions LLC, said it planned to build its own tower about 1,000 feet east, which CyrusOne says would obstruct communication to and from the data center. CyrusOne sued to block Scientel’s tower. At the moment, Scientel’s development on its 2.6 acres consists of a construction trailer, a portable toilet, and a pile of metal poles.

The unlikely catalyst for this gazillion-dollar standoff is a collection of elected officials in Aurora, a quaint river town best known as the fictional setting for the Wayne’s World movies. The Aurora City Council approved the CyrusOne tower, then turned Scientel away at CyrusOne’s behest, then flip-flopped and approved the Scientel tower, which sent CyrusOne’s lawyers running to the federal courthouse in Chicago, where the case has ground on for more than a year. CyrusOne, Scientel, and CME declined to comment for this story.

It isn’t clear that the Aurora council fully comprehended the legal and technological issues involved in allowing the Scientel tower. Alderman Bill Donnell, a retired parks director who changed his Scientel vote from no to yes, says he didn’t understand at first “how important we are” in the high-frequency trading arena. “I came from being a guy who didn’t know where the cloud was to realizing speed matters,” he says. “I didn’t realize being a millisecond faster was all that important.”

Traders’ quest for the slimmest sliver of advantage is as old as markets. In the 19th century, Reuters used carrier pigeons to speed the delivery of stock prices. More recently, Chicago pit traders donned platform shoes so they could see and be seen better on crowded trading floors. Today, getting an edge is all about the speed of light: 186,282 miles per second.

In his 2014 book Flash Boys, Michael Lewis describes how a startup called Spread Networks dug through mountains and tore up parking lots to lay what became the straightest fiber-optic line between trading centers in New Jersey and Chicago, because the more direct the line, the faster data zipped through it. When Spread’s service made its debut in 2010, it could shoot trades from Chicago to the Nasdaq data center in Carteret, N.J., in less than 7 milliseconds (a millisecond is one-thousandth of a second). In other words, the data line moved information at about two-thirds the speed of light.

By the time Lewis’s book came out, Spread’s technology was essentially obsolete for trading, overtaken by microwave radio transmissions, which can carry data through the air at about 99 percent the speed of light. Microwaves are faster because the glass or plastic in fiber-optic lines slightly impedes signals; air poses less obstruction. Also, microwave networks generally require less work and cost to build than fiber line does, partly because the U.S. is dotted with cell towers that can accommodate microwave antennas. The usefulness of Spread’s service dwindled to the point that the company, which according to Lewis spent about $300 million to launch its network, was sold for $131 million a year ago to Zayo Group Holdings Inc.

Microwave networks rely on line-of-sight transmissions—a microwave dish has to be able to see the dish it’s communicating with. The Earth’s curvature forces traders to relay their signals from towers that are typically spaced every few dozen miles. Tall spots that see farther can stretch those distances; some firms are licensed to use antennas atop the Willis Tower (née Sears), Chicago’s tallest building.

The CME data center owned by CyrusOne sits on the southwestern corner of an intersection just south of an Interstate 88 exit. Most of the wireless dishes belonging to traders are on three tall towers kitty-corner from the center. New Line, McKay, and DRW, by getting just a few hundred feet closer, have a measurable advantage. McKay says its system can zing a trade from Aurora to Carteret, or Carteret to Aurora, in 4 milliseconds, roughly a hundredth of the time it takes a major-league fastball to reach home plate.

In March 2016, CME sold the building for $131 million to CyrusOne, a real estate investment trust that owns more than 40 such centers and now leases the Aurora site to CME. CyrusOne announced an expansion, then laid plans for its tower, which the Aurora City Council approved in March 2017. The city required CyrusOne to lease traders space on the tower at fair market rates; the intent was to “equalize wireless access to the CME,” the company says in court filings. The matter seemed settled. Then, two months later, Mayor Richard Irvin took office.

Irvin, a former prosecutor and criminal defense attorney who was born and raised in Aurora, won the mayoral seat partly on his vow to expand the local economy. He’d barely taken the oath of office when Scientel came calling. Irvin was keen to listen.

The company told the mayor it wanted to move its headquarters from another Illinois town to a patch of vacant Aurora land near the CME data center. There was a catch: Scientel would bring its 50 jobs and their $100,000-a-year average salaries only if Aurora let it build a 195-foot-tall communications tower on the site.

Aurora isn’t a small town—with a population of 200,000, it’s Illinois’s second-largest city after Chicago—but it has that feel, with century-old buildings and an overhead train trestle winding through downtown. Condos and restaurants have sprouted around the grandiloquent 87-year-old Paramount Theatre and an 8,500-seat concert venue along the Fox River. Irvin thought Aurora could do even better, and in particular it could be getting more value from the fiber-optic ring the city built over the past decade on land around the I-88 interchange near the data center. The land was undeveloped, and only about 5 percent of the ring’s capacity was in use.

Scientel, based 15 miles away in Lombard, Ill., designs, installs, and maintains wireless networks that help municipalities link police departments, medical centers, and other vital facilities. From a new $4.5 million headquarters at the I-88 exit, Scientel proposed to use its tower with Aurora’s fiber-optic ring. The company made little if any public mention of doing any business with traders.

“This area is very attractive to us,” Scientel President Nelson Santos told the Aurora Planning Commission in September 2017. “Our customers need to get to the cloud, and this is the way to do it.” The Planning Commission recommended that the City Council endorse Scientel’s tower plan.

This wasn’t going over well at CyrusOne, which with $800 million in annual revenue dwarfs Scientel, at about $20 million. Within days of Scientel’s formal tower request, CyrusOne was scheming to torpedo it. “If you can get the [Scientel] tower coordinates so we can see where exactly they want to place their tower, then we can do a [frequency] study and come up with some reasons for objecting,” an outside engineer for CyrusOne emailed another engineer in June 2017, according to federal court filings. Other CyrusOne emails showed that the company “assembled a team of lawyers and technical people” to work against Scientel’s tower, a federal judge found in a recent ruling.

CyrusOne has asserted in court that its main concern was that Scientel’s proposed tower would interfere with transmissions from CyrusOne’s tower. The Scientel structure would “block 50 percent of the transmission from our tower,” a CyrusOne attorney later told a federal judge. “So our tower will essentially be useless for the purpose that it’s being built for.”

CyrusOne representatives pressed the point to Aurora aldermen. At a meeting in November 2017, the City Council voted 7 to 3 to deny Scientel its tower. The mayor—who didn’t have a vote—wasn’t pleased. “What the aldermen pretty much said was they don’t want 50 jobs,” he told the local Beacon-News. He had staffers lobby council members, emphasizing Scientel’s contention that only the Federal Communications Commission—not Aurora—could legally decide whether one tower might interfere with the other.

The council reconsidered in January 2018. A top Scientel executive told the council the company couldn’t afford space on CyrusOne’s as-yet-unbuilt tower for at least $6,000 a month. Also, because Scientel would be working with safety agencies, it would need around-the-clock access that would be hindered by the data center’s strict security procedures. Now the council swung in Scientel’s favor, 9 to 3.

When Irvin made his State of the City Address in April at the Paramount, Scientel chipped in $10,000, the biggest political contribution the company had ever made. By then, CyrusOne had sued Irvin, the City Council, and Scientel.

Two unsettled questions dominate the thousands of pages filed in federal court: Would the Scientel tower in fact interfere with CyrusOne’s? And what motivated Scientel to place its tower on that particular spot?

Microwave transmissions can become garbled or be blocked altogether when two entities send data over the same electromagnetic frequencies or when something—a mountain, say, or a skyscraper—blocks a network path. Part of the problem in determining whether Scientel’s tower would interfere is that it doesn’t yet exist, and CyrusOne’s tower, though it’s standing, doesn’t yet have any antennas on it.

In court, arguments about interference have revolved around dueling scientific analyses that seek to anticipate where data flowing to or from one tower might encroach on data from the other. CyrusOne maintains that the Scientel structure would pose an obvious line-of-sight obstruction, particularly on the lower portion of the CyrusOne tower. If potential clients balk at placing dishes there, it could cost CyrusOne as much as $1.7 million in annual revenue, the company said in a court filing.

Scientel counters that CyrusOne has resisted providing specifics about the frequency bands that CyrusOne’s trading clients could use, thus preventing Scientel from engineering its tower to avoid conflicts. All sorts of other nearby utility towers could, in theory, block CyrusOne, Scientel says, but CyrusOne isn’t complaining about those. Scientel has also tried to broaden the issue. “What if Scientel sought to build a hotel due east of CyrusOne?” the company said in a court filing. “Could CyrusOne stop that?”

Scientel says it chose its site because it was affordable and offered easy access to Aurora’s fiber-optic ring and I-88. “In reality, this case has nothing to do with the potential interference of radio waves,” it said in court documents. The suit was about CyrusOne’s “quest to be a monopolist tower landlord.”

Still, the case raises the obvious question of why Scientel would plant its tower right where critical streams of data are flowing if it didn’t want to interfere—unless, of course, the company has designs on getting into the trading business. In court filings, Santos avers that Scientel “is not a trading firm.” But the company does have a foothold in the industry.

Like trading companies, Scientel has FCC licenses to transmit between Aurora and New Jersey. Two years ago, it sued a former employee for allegedly stealing proprietary documents. The title of one allegedly pilfered file contains the phrase “ICE - NY4,” an apparent reference to Intercontinental Exchange Inc.—a significant futures market and the owner of the New York Stock Exchange—and to a key data center in Secaucus, N.J. “This file contains a line-by-line cost estimate for an upcoming project for one of Scientel’s largest clients in the financial industry,” says a document in the lawsuit. Another file, partly titled “Aurora to NY4 Link Data,” referenced Scientel’s plan for a wireless network from Aurora “to a financial exchange in New York City,” designed for a potential, unidentified client.

Scientel has said it will equip its Aurora tower with 28 antennas—24 for public safety and municipal use and four for “private” purposes. In court filings, the company has resisted being more specific, saying the names of its customers are proprietary. In the trading community, “everyone is trying to figure out who they are,” says McKay Brothers co-founder Stéphane Tyč. These sorts of riddles are common. When traders started launching microwave networks, they operated in secrecy, seeking to avoid tipping off rivals. Today, they still work through shell companies: Webline Holdings LLC is DRW, World Class Wireless LLC is Jump, and so forth.

As for Scientel’s potential trading partner, maybe the company plans to team up with an unknown up-and-comer looking to join the big leagues, or another large trader that currently uses a third party like McKay and now wants its own network. But the name that keeps coming up among industry sources is Citadel. That could be Citadel LLC, the Chicago-based hedge fund founded by billionaire Ken Griffin, but a more likely candidate is Citadel Securities, Griffin’s giant trading company. Citadel Securities handles roughly a fifth of all the volume in the U.S. stock market, not to mention whatever it does at CME. If the firm currently employs one of these amped-up networks, it’s not clear which it is. But for a company of its size and ambition, it’s easy to see how Citadel Securities might want to avail itself of such a network under the cloak of a discreet partner or an anonymous shell firm. Then again, Griffin, who just spent $238 million on an apartment overlooking Central Park in New York, can probably afford to build his own wireless network. Citadel didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.

Meanwhile, local politicians such as Irvin have become unlikely kingmakers in the global trading system. Not that he wants to be. “If McDonald’s decides they want to set up right next to Burger King,” Irvin says, “all I care about is now we have two retail establishments—and this makes me happy.” He wishes CyrusOne and Scientel would find a way to get along so Scientel can build that new headquarters already.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.