How the Danish Justin Bieber Made It Big in China

If a handsome Dane whose Mandarin teacher worked with a famous badminton champion can’t make it big in China, who can?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Two hours before the concert was scheduled to begin in Shanghai’s Xuhui District, young women were already lined up outside a coffee shop under a pink neon sign that read, “Please don’t tell my Mom.” One wore a hooded sweatshirt with the name and face of the night’s performer, the Danish pop star Christopher Nissen. Others dressed, for unclear reasons, like Harry Potter and his classmates. Most wore all black, as they’d been instructed on the invitation.

When the doors opened, around 7 p.m., on a Monday evening last December, these early birds—many of whom had already intercepted Nissen the night before at the airport—swarmed to the front row, bypassing a table with free snacks and drinks. They were followed, at a more leisurely pace, by ad agency executives and social media influencers, who’d come at the invitation of the night’s sponsor, Dynaudio, a Danish stereo company. Guests chatted through a presentation about Dynaudio’s new wireless speakers, then hushed when a Chinese emcee standing on a makeshift stage in the front of the room introduced the night’s musical guest.

Nissen ambled out wearing a V-neck white T-shirt and a black leather jacket. “Is this your first time in Shanghai?” the emcee asked him in English.

“Noooooo,” the crowd answered for him.

“They know,” Nissen said, beaming.

He dedicated his first song, Heartbeat, to the fans who met him at the airport and later performed a brief verse in Mandarin. “It’s my little party trick when I’m out here,” he said, with a knowing wink. The girls in the front row roared.

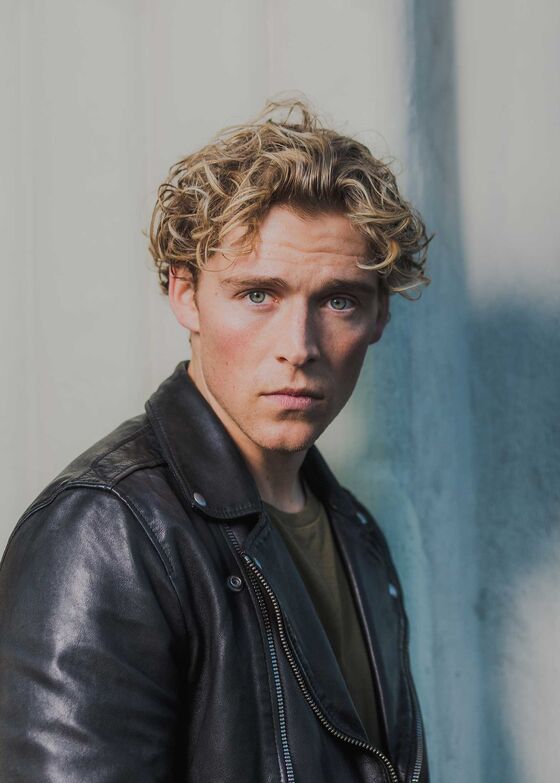

Nissen is 27. He has sandy hair, blue eyes, a strong jaw, and looks like he walked off the assembly line from some global pop star factory—which, in a sense, he did. To his fans, he’s known simply as Christopher; to his record label, Warner Music Denmark, he’s “the Danish Justin Bieber.” He performs songs in English, almost exclusively about romance. Tracks from his recent album include Naked, Baby Making Interlude, and All About Sex. In his latest mildly suggestive single, Monogamy, he croons, “These pretty girls they tryna get me confused/ Though I get cravings, they got nothing on you/ Damn, it’s so tempting, but I leave on my own/ My heart is hungry, but I eat home.” Then it suggests that the listener “put that sexy thing on top of me.”

Critics may find Christopher’s songs unimaginative, and he’s never cracked the Billboard Hot 100, that U.S. measure of pop stardom. But he is huge in two places: Denmark and China, the latter of which has adopted him as its native son. All of the 12 singles he’s released in China since 2014 have broken into the top 10; eight have gone to No. 1. He’s performed in several of China’s largest cities, and he’s become a spokesman for Huawei Technologies Co., the Chinese telecom company.

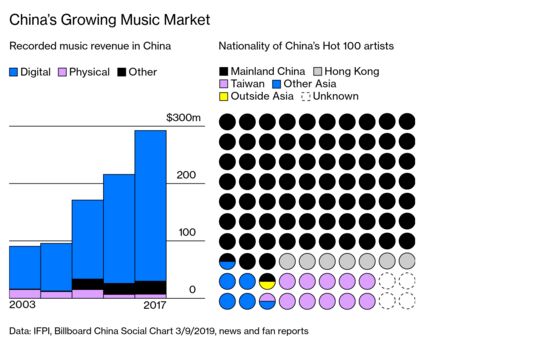

Being big in China didn’t used to mean much. In 2013 the music industry made less money there than it did in Denmark. Piracy was so pervasive that Baidu Inc., the Chinese Google, had been branded a copyright infringer by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, which represents the world’s big record labels. That’s changed. Baidu now runs a streaming music service that pays for rights, and other big Chinese internet companies have invested billions of yuan into their own streaming services. In 2017, China became one of the world’s 10 biggest music markets for the first time. By next year, it could be in the top five.

Major music labels and artists have scrambled to capitalize, striking deals with the streaming services and opening offices. “China could be the biggest and healthiest music market in the world, if we get it right,” says Alex Taggart, a consultant with Outdustry Group, which advises record labels and artists on marketing themselves there. Beijing has limited access to much of the Western internet—and, therefore, Western pop music. Katy Perry, U2, Maroon 5, Bon Jovi, and Bieber are all banned from performing. (The reasons are varied and not always clear. Perry was blackballed for expressing support for Taiwan; Maroon 5, Bon Jovi, and Oasis for supporting Tibetan independence; Bieber for “bad behavior.”) Local artists account for more than 80 percent of listenership in China. The rest is a mix of U.S. pop, Korean pop, and electronic dance music, or EDM.

That makes Christopher a pioneer of sorts in China. He already makes more money there than he does in Denmark, or anywhere else, and has been to the country eight times over the past four years. He’s taking Mandarin lessons and hopes that a new album will make him a household name from Guangzhou to Harbin. “There is no clear way to do it in China,” he says. “It’s such a young market, especially for international artists. Can we build it from the ground up? I am an experiment.”

Christopher grew up in a suburb of Copenhagen. He says he’s wanted to be a pop star since he was 10, when he first listened to Justin Timberlake and Michael Jackson. His parents indulged their son by buying him a guitar and listening to his impromptu concerts in their living room. Christopher taught himself how to play by watching videos online.

In the third grade, he performed in public for the first time at a school competition, singing an original song in Danish. In the song Are You Coming to the Party Tonight?, the prepubescent Dane warned a girl that he’d never be able to love again if she turned him down. Christopher won the talent show and spent the next few years performing at any venue that would have him, most often at an Italian wine bar across the street from his high school.

At 17 he walked into the Copenhagen offices of EMI Denmark (now part of Warner) without an invitation. His hands were so sweaty that he could barely hold his guitar while he strummed a John Mayer song. Even so, an executive invited him to play his own songs for a small crowd. Three days later, EMI called Christopher’s parents and offered to sign their son. His parents agreed, with one condition: He had to finish school. He adopted the first-name stage name and got busy writing songs.

His debut record included a few catchy tunes, but his second, Told You So, was a hit. The title track topped the charts in Denmark and won Pop Album of the Year at the 2014 Danish Music Awards. Advertisers, concert promoters, and reality TV producers all came calling; Christopher said yes to everything, playing 150 shows that year in Denmark. “My face was on 12 million water bottles,” Christopher says. “I was on every poster in every gas station.”

Having conquered the Danish fuel and beverage markets, he and his record label started exploring opportunities abroad. The music video for his song Copenhagen Girls had gotten 10 million views on YouTube, and some of those views had to come from outside Denmark. Christopher traveled to showcases in Germany, Norway, and Sweden—but the shows didn’t lead to any new business opportunities, let alone offers to play in the U.K. or U.S.

Unused to being rejected, Christopher tried to understand what went wrong. He’d been careful to avoid the trap of many Danish singers, who write songs for their own country. “You can tell it’s a guy who grew up right around the corner,” he says. People told him he sounded “Justin Timberlake-ish,” which wasn’t necessarily a compliment. Crooners were increasingly losing radio play to big-name EDM artists and their pop star collaborators. Moreover, the love-song market in every other country seemed to be dominated by domestic talent. Ultimately he decided his music just wasn’t up to global heartthrob industry standards. “Copenhagen Girls was good, but not a worldwide smash,” he says.

There was one bit of good news: Christopher’s manager told him that the track was near the top of the charts on QQ Music, a streaming service owned by Tencent Group Holdings Ltd. that’s the most popular in China. Christopher had never heard of QQ before—nor had he ever been to Asia—but it was all he needed. He booked a flight to China.

Because it’s still a relatively small market in terms of revenue, China generally has been treated by most international musicians as part of a broader plan for Asia—adding stops in Beijing and Shanghai to a tour that includes Hong Kong, Seoul, Tokyo, and other major cities. This works for the handful of global superstars—Bruno Mars and John Legend, for instance—but for most artists, it’s not an effective way to get big in China. To do that, according to Warner Music China Chief Executive Officer Andy Ma, who helped Christopher develop his strategy, you need to slug it out in second-tier cities such as Chengdu, Guangzhou, Nanjing, and Wuhan. The concerts won’t be moneymakers, Ma says, but they’re crucial to building an audience in the country. Otherwise, he says, “they won’t remember you.”

Christopher made his first visit in 2014 to perform on TV shows in Shanghai and Changsa, 600 miles west in Hunan province. From Day 1, Ma decided to position him as less aloof than the typical pop idol. He needed to come off as funny and personable but not silly. Chinese talk show hosts love to subject celebrities to weird challenges, dares, and activities. No matter what they ask, label executives told him, just go with it.

During an appearance on a late-night show—the Chinese equivalent of The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon—the host asked Christopher to pull up his shirt and show off his six-pack. Christopher appeared startled at first and then obliged. Over the next couple of trips, he ate pork intestines and jellyfish on national TV. He sat down for awkward interview after awkward interview, putting on blindfolds and sharing his workout routine. “You feel like you are losing your artistic integrity. Now I’m just a monkey,” he says with a laugh. “But you trust your label people.”

Christopher’s third album, Closer, was something of a disappointment when it was released in 2017. One song, I Won’t Let You Down, topped the charts in Denmark, but it didn’t rate anywhere else in Europe or in the U.S. China was another story. Heartbeat, an ode to his fans, was No. 1 on the QQ charts for eight consecutive weeks, racking up 250 million streams. Pop ballads, passé in Europe, are still all the rage in China, says Karl Rubin, a producer who’s worked with popular musicians in the country. “China is really hyped on 2014 pop music,” says Rubin. Warner felt confident enough in the appeal of Christopher’s love songs to send him on a two-week tour.

The first rule of touring in China: Don’t pull a Björk. The avant-garde Icelandic performer ended a 2008 concert in Shanghai by singing Declare Independence, a track meant to support activists in Greenland and the Faroe Islands but which Björk has since repurposed for other areas. Her adapted lyrics for the occasion: “Tibet, Tibet/ Raise your flag!” The incident prompted international headlines and a Chinese government clampdown. Today foreign artists must obtain a special visa to perform in China, which in some cases requires them to submit a passport, headshot, biography, playlist, lyrics of all their songs translated into Mandarin, and a video of everyone who will appear onstage.

Ahead of his first solo show in Beijing, Christopher was less worried about Chinese censorship—love songs are generally OK, as long as they’re not explicit—than he was about the possibility that nobody would show up. The charts in China are notoriously difficult to trust or understand. There’s no Billboard-like central body that issues weekly sales figures. Musicians are forced to rely on QQ’s charts and social media followings. “I don’t know if there will be 29 people or 300 or what,” he told his crew. “But we will convert them.” The show was sold out. In addition to Beijing and Shanghai, Christopher would pack venues in Chengdu, Guangzhou, Nanjing, and Wuhan, none of which he’d heard of before the trip.

He was scheduled to perform on the Hito Awards show in Taiwan alongside Eric Chou, a pop star known as “king of the lovelorn people.” They would do one song of Christopher’s and one of Chou’s. Warner Music suggested Christopher sing the chorus to Chou’s song in Mandarin. He pulled it off, in front of about 15,000 people. “That was the first time I felt like I could see and feel the success,” he says.

In 2018, Christopher started to take Mandarin lessons. Unlike the major languages of Europe, it’s tonal, meaning one character can be pronounced five different ways, conveying five different meanings. Christopher has spent entire lessons learning just a few words. Dissatisfied with his progress, he recently reached out to his countryman Viktor Axelsen, who—along with being a former world-champion badminton player, Olympic medalist, and big-time celebrity in Copenhagen—is conversant in the language. He connected Christopher with his Chinese teacher. Even so, progress has been slow. “Being able to answer a few questions in Mandarin would make a huge difference,” Christopher says.

Backstage after the Dynaudio event in Shanghai, he seemed worn down from the strain of his latest two-week sprint through Asia. He was about to take a 5 a.m. flight to Beijing, where he had a half-dozen performances booked in one day. During the previous 24 hours, he ate squid ink jelly, dressed up as a fashionista’s personal assistant, and offered his opinion to various media outlets on home furnishings and superheroes. “I can’t think of any artist who would do half the shit I did yesterday,” he said, trying to relax in a chair alongside his manager and keyboard player. He drew the line when asked by an interviewer to wear a pink tutu and crown. “You have to know when to say no,” he said.

The fatigue lifted, briefly, when Christopher learned of another business opportunity. Chinese artists, a publicist said, livestream on QQ Music, earning gifts, including sports cars, from fans who can spend thousands of dollars during a stream. “Daaaaaaaamn,” Christopher said. “Hook a brother up with a livestream session.” The publicist then clarified, awkwardly, that he meant digital sports cars, not actual sports cars, but that didn’t deter Christopher’s enthusiasm for trying it.

The relationship between virtual and real is something he’s been exploring in his music. Among the singles he promoted in Shanghai was Irony, about his addiction to social media, its role in his success, and the falseness of its images. Irony peaked at No. 7 in Denmark and got to the top 10 in China. The song, he says, is an artistic turning point as he seeks to expand his subject-area repertoire beyond love. “I have some songs that are even better,” he says. “They have a more international approach and sound.”

Christopher’s strategy for his fourth release is to build on his momentum in China and give Europe another shot. He’s just released an album called Under the Surface, and he plans to tour Germany in May. He’ll also tour Asia in June, including stops in Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Shanghai, and Beijing.

At the end of the night in Shanghai, Christopher walked back downstairs to take photos with the fans who’d been waiting for four hours. A woman in her early 20s, wearing a black peacoat and bright red lipstick, had been preparing for her moment with phone and autograph pad in hand. When the time came, she rushed over to meet him and snapped a picture, using a digital filter to superimpose a cat emoji resting underneath his chin. She left, beaming, with an autograph that read, “For Dasy, From Christopher.” It ended with a heart sign, scrawled in gold lettering. Later that night, she uploaded a photo of the page to Instagram and captioned it “See u again.” There’s no doubt she will.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jim Aley at jaley@bloomberg.net, Bret Begun

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.