Levi Strauss Is Betting on Tops

The maker of iconic jeans wants to jump into other parts of the wardrobe.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In 1873, German immigrant Levi Strauss founded an industry when he began outfitting California gold miners with blue jeans. His company evolved by innovating—adding belt loops, for example—and expanding its product line, making clothing for women, kids, and teenagers. By the middle of the last century, Levi’s jeans were an American icon.

In the 1980s competition from the likes of Calvin Klein and Gap dethroned Levi Strauss & Co. Fashion shifted away from denim, to khakis in the 1990s and more recently to athleisure’s mix of workout gear and casual clothing, adding to its woes. Now the company synonymous with pants says it’s found a strategy to revive its past glory: tops.

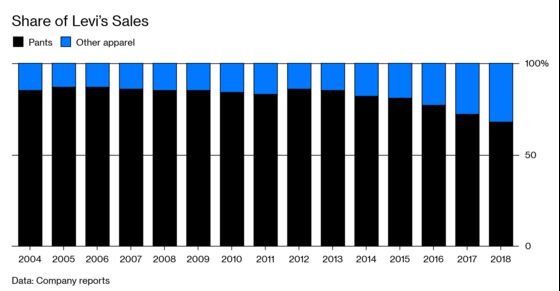

Sales of Levi’s tops doubled in the past five years, to more than $1 billion. The category—encompassing button-downs, sweatshirts, and fleece cover-ups—generated more than half the company’s growth during that period, and now accounts for about 20 percent of revenue. That success is the main reason its executives decided to take Levi’s public again. They can pitch investors on the brand’s ability to evolve, this time into a label making everything from hats to shoes. “That’s the goal, to be more than just a jeans brand,” says Michael Zuccaro, an analyst for Moody’s Investors Service who covers the company’s publicly traded bonds. The growth in tops “shows people are buying the brand, it’s not only Levi’s bottoms.” He adds that changing the consumer’s mind about a brand is extremely hard to do.

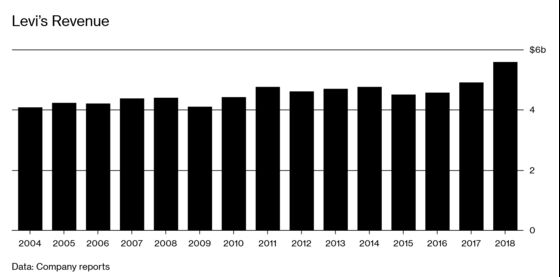

Prior efforts to get beyond men’s jeans faltered, and sales slowly declined, dropping from $7 billion in 1997—almost $11 billion today, adjusted for inflation—to $4.1 billion in 2009. But last year the company posted $5.6 billion in sales, representing growth of 14 percent, its best mark in more than a quarter century. Tops played a major role, growing 37 percent, almost five times the rate of pants.

During that same 20-year stretch, Nike Inc. crossed over into fashion from athletic performance and increased revenue to almost $40 billion. But it’s an outlier. After initial breakthroughs, many brands fail to make the leap into new categories. Under Armour Inc., struggling to become a fashion brand, has stepped back from a push into trendier attire.

A visit to Levi’s flagship store in New York’s Times Square shows how hard it’s trying. Just beyond the entrance, the first thing visitors see are piles of T-shirts, sweatshirts, and accessories. The company has struck a licensing deal with Peanuts, a comic franchise with broad nostalgic appeal, so there are Snoopy backpacks, jackets, hats, socks, and even boxer briefs. Jeans are nowhere in sight, until you head to the basement.

The shift to tops has been led by Chip Bergh, who became chief executive officer in 2011. He arrived after almost three decades at Procter & Gamble Co., where he helped integrate Gillette after its $61 billion acquisition and then ran the men’s grooming unit. When Bergh joined Levi’s it was overloaded with debt—the result of a leveraged buyout by the founding family, who took the company private in 1985 and spent billions more purchasing shares from other Strauss descendants to consolidate ownership.

Bergh, who declined to comment for this article, replaced most of the top management, paid off debt, and cut costs, including reducing the head count by about 7 percent. That freed up capital, allowing him to embark on a classic brand expansion strategy: He boosted marketing—among other things, acquiring the naming rights to the stadium of the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers—and began expanding sales overseas. He opened a product lab a few blocks from the San Francisco headquarters to speed innovation, and in 2015 relaunched Levi’s women’s business, which has seen its sales increase for 14 straight quarters.

Levi’s now makes jeans blended with Spandex to add stretch—and comfort. Revenue from Asia and Europe has grown to 45 percent of all sales. Bergh has multiplied the number of company-operated stores by 75 percent, to more than 800, giving it a bigger platform to reshape its image. “Everywhere I look I see upside” and “someday a $10 billion brand,” Bergh wrote in a piece for the Harvard Business Review last year.

In late February, Levi’s disclosed plans for an IPO, targeting a share price of $14 to $16. In a positive sign, on March 20, Levi’s sold 36.7 million shares at $17 each, raising $624 million. The stock was set to begin trading on March 21.

There are still plenty of risks for investors. While profitability has improved, sales growth has averaged less than 3 percent a year since Bergh’s arrival, though it’s accelerated since 2017. The company points to China as a market with lots of potential. The country, which accounts for 20 percent of the global apparel market, contributes just 3 percent of Levi’s sales, or $167 million. But its economy is slowing.

Then there are people like Willy Davis, a stylish 37-year-old from Harlem. He bought his first pair of Levi’s jeans a couple of years ago and says he loves the fit. As he shops the Levi’s department at Macy’s flagship store in Manhattan, he barely notices the shirts. Two-thirds of the company’s sales still come through Macy’s and other wholesale accounts, and in these locations, the focus remains piles of jeans. “I’m not really feeling their tops,” says Davis, a program supervisor at Manhattan’s Intrepid Museum. “I grew up thinking Levi’s jeans, and I guess that’s how a lot of people think.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net, James Ellis

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.