The Swedish Supercar Maker Aiming to Fight Ferrari at 249 MPH

Koenigsegg plans to boost production to hundreds of cars a year.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Over the next three years, Ferrari NV aims to double profits by dramatically boosting sales of fast and fabulous cars such as the $1.8 million Monza, the $2.1 million LaFerrari Aperta, and the Purosangue, a sport utility vehicle that promises to be one of the fastest rides on or off the road. To get there, the Italian manufacturer will have to contend with Christian von Koenigsegg.

Since 2002 his company, Koenigsegg Automotive AB, has sold about a dozen hand-built cars annually for roughly $2 million apiece. He expects to increase his yearly production to hundreds of vehicles by 2022, almost all of them a new model priced around $1 million. And a few years after that, he hopes to boost output to thousands of autos a year—which would make his company a serious threat to Ferrari and other makers of supercars such as Lamborghini and Bugatti. “Some people already choose our cars instead of a Ferrari,” von Koenigsegg says on a tour of his factory on the flat green outskirts of the Swedish town of Angelholm. While the car is “still incredibly expensive, the potential sales volume increases massively.”

Koenigsegg in January signed a $320 million deal with National Electric Vehicle Sweden AB, or NEVS, a Chinese-controlled company that bought the assets of Saab out of bankruptcy in 2012. The partners will start making the new model in 2021 at a sprawling complex of gray and yellow buildings in Trollhattan, three hours north of Angelholm by car (or perhaps less in a Koenigsegg, with its top speed of 249 mph). While the Saab plant today is a virtually empty shell, it once employed 8,000 workers and had the ability to churn out as many as 200,000 vehicles a year.

That’s a stark contrast to Koenigsegg’s current digs, where 225 workers make some of the world’s most sophisticated vehicles using artisanal production methods. The place feels more like a social club for car buffs than a 21st century factory, with a foosball table, comfy chairs, a half-completed jigsaw puzzle—and nary a robot in sight. Almost all the components are made in-house: carbon fiber lamp cases and wheels, chassis, and engines engraved with the signature of the person who built them. Groups of employees in jet-black slacks and sweaters sit at tables chatting and hand-polishing metal parts. In one enclosed area, two people in hazmat suits and respirators sand and shape carbon fiber components with delicate tools that wouldn’t be out of place in a sculptor’s studio. “One of the things I want to do here is create technology that trickles down and helps improve cars,” says von Koenigsegg, 46.

For the past two years, the company’s engineers have been developing the model, which will feature an engine that allows independent control of the intake and exhaust valves. They say that technology, which von Koenigsegg ultimately aims to license to other manufacturers, can deliver faster acceleration with almost 50 percent more torque than conventional engines while cutting fuel consumption and emissions. He’s tight-lipped about other details, declining to say whether the car will be a two-seater, include versions such as an SUV, or match the speed of the current model. “If I tell you one small thing, it means I tell you everything,” he says with a grin.

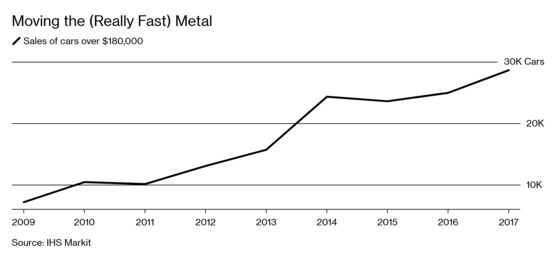

Global sales of ultrapremium cars—costing more than $180,000—quadrupled, to 28,650, from 2009 to 2017, according to researcher IHS Markit, and those numbers are likely to grow as the ranks of the super rich continue to swell. But Koenigsegg still has a long road ahead, says Philippe Houchois, an analyst with Jefferies in London. Ferrari’s nine decades of production give it a catalog of historic models it can revive and update. With shipments of more than 9,000 cars a year, it can more easily turn a profit by spreading development costs across a greater number of vehicles. “About 10 or 12 years ago, it was quite rare to get very high-end cars, and every time there was one, there was buzz in the industry,” Houchois says. With the economic boom of the past decade, “there’s been a sudden proliferation of special-edition, multimillion-dollar cars.”

Von Koenigsegg was already familiar with the NEVS team. In 2009 he bid on Saab’s assets, but he balked at the conditions demanded by Swedish government officials. When NEVS bought what was left of the Trollhattan complex, it invited manufacturers—including Koenigsegg—to test their vehicles at Saab’s old facilities. Today, in a corner of the vast production halls, a parade of cars from across Europe are evaluated for emissions, durability, and adaptability to extreme heat or cold reproduced in what the company calls a “climate chamber.” With a $930 million investment from Chinese tycoon Hui Ka Yan in January, NEVS will make battery-powered sedans based on the old Saab 9-3 underpinnings, as well as the new Koenigsegg. A few months ago, “the focus was merely on survival,” says NEVS Executive Director Stefan Tilk. “Now I get phone calls from people at major carmakers looking for a job.”

The two sides are still nailing down the details of the supercar plan, and many questions remain. But von Koenigsegg brims with ambition and says he’s accustomed to skeptics doubting his grand visions. He first came up with the idea of building supercars at age 22, shortly after finishing school. Naysayers predicted he was doomed to fail because customers would be unwilling to pay the true cost of a hand-built car, and development expenses could only be borne by established automakers. “The chances of succeeding were so slim,” he says. “But since we barely had the right to exist, we turned out to be difficult to kill.”

--With assistance from Blake Schmidt.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.