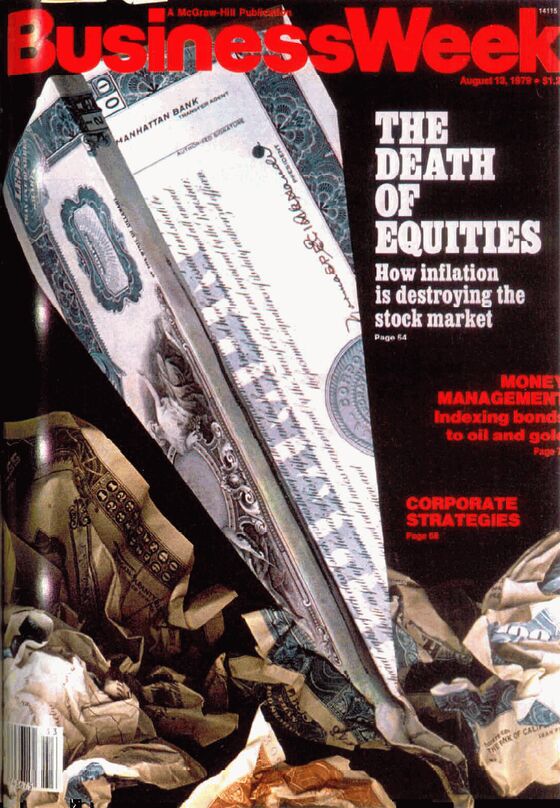

It’s Been 40 Years Since Our Cover Story Declared ‘The Death of Equities’

And people never tire of reminding us of the bull market that followed.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- We’re still getting grief for a cover story that appeared in BusinessWeek—the ancestor of Bloomberg Businessweek—four decades ago. On Aug. 13, 1979, the headline on the cover was “The Death of Equities: How Inflation Is Destroying the Stock Market.” Three years after that article appeared, the stock market hit bottom and then began a remarkable resurgence. The total return on the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index since its 1982 low, with dividends reinvested, has been nearly 7,000%. Not bad for a corpse.

Our “Death of Equities” cover is so famous among contrarians—investors who bet against the conventional wisdom—that any article anywhere that includes the phrase “death of ...” immediately provokes reminders of our less-than-finest hour. Look at the Wikipedia entry for Magazine Cover Indicator for a taste.

It would be nice to claim that the cover language overstated the article’s premise, but no. Here are three excruciating excerpts:

“Further, this ‘death of equity’ can no longer be seen as something a stock market rally—however strong—will check. It has persisted for more than 10 years through market rallies, business cycles, recession, recoveries, and booms.”

“To bring equities back to life now, secular inflation would have to be wrung out of the economy, and then accounting policies would have to be made more realistic and tax laws rewritten.”

“For better or worse, then, the U.S. economy probably has to regard the death of equities as a near-permanent condition—reversible some day, but not soon.”

I called up Seymour Zucker, who was editing economics coverage for the magazine in 1979 but was not involved in the un-bylined article and is now happily retired in Brooklyn. He was succinct: “Well, I guess we were wrong about that.”

Now allow me to offer a partial defense of “The Death of Equities.”

First, the article remained correct for three years after it was written. In the world of journalism, three years is almost forever. To avoid being deemed inaccurate, an article has to remain correct only from the time it’s written until the time it reaches readers. After that, it’s like a fledgling bird that has flown from the nest. It’s on its own. If financial journalists could truly see the future, we wouldn’t be typing for a living. We’d be on an island somewhere. Other than Manhattan.

Besides, in the three years after the cover story appeared, stocks fell and inflation rose, meaning that stocks really were comatose, if not dead. Justin Lahart of the Wall Street Journal—bless his heart—observed in 2005: “And that August 1979 Business Week cover story wasn't quite as wrong as people remember. When it came out, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was at 867. Three years later, it was at 779. Adjust that for inflation, the Dow had fallen 32%.”

“The Death of Equities” captured what a lot of smart people on Wall Street were saying at the time. Stocks were not performing well as a hedge against inflation. The winning investments were gold, stamps(!), diamonds, and single-family houses. Individual investors were bailing out—7 million fewer shareholders in 1979 than there had been in 1970. The end of fixed commissions had drained profits out of stockbroking. And companies were buying back shares.

The main thing we missed is that the era of high inflation was about to end, thanks in large part to Paul Volcker, who was appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve on Aug. 6, 1979. That was probably right after that cover story was put to bed. (He was not mentioned in the article.) Volcker’s Fed wrung inflation out of the system by putting the U.S. economy through a punishing pair of recessions between 1980 and 1982.

Another point in partial defense of “The Death of Equities” is that it had some great reporting. My favorite bit is about funds that were putting money into unconventional assets instead of stocks. “In 1974, for example, the British Rail Superannuation Pension Fund sank $58 million into fine arts, ranging from Picasso’s Young Man in Blue to 12th century candlesticks.”

So “The Death of Equities” wasn’t all bad. Still, kind of embarrassing.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.