Did Capitalism Kill Inflation?

If economics were literature, the story of what happened to inflation would be a gripping whodunit.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- If economics were literature, the story of what happened to inflation would be a gripping whodunit. Did inflation perish of natural causes—a weak economy, for instance? Was it killed by central banks, with high interest rates the murder weapon? Or is it not dead at all but just lurking, soon to return with a vengeance?

Like any good murder mystery, this one has a twist. What if the apparent defeat of inflation blew back on the central bankers themselves by making them appear expendable? Far from being lauded for a job well done, they’re under populist attack. “If the Fed had done its job properly, which it has not, the Stock Market would have been up 5000 to 10,000 additional points, and GDP would have been well over 4% instead of 3% … with almost no inflation,” President Donald Trump tweeted on April 14. On April 5, channeling Freddie Mercury of Queen, he said “you would see a rocket ship” if the central bank eased up.

The irony of Trump’s criticism of the Federal Reserve is that by historical standards, the bank is remarkably dovish—that is, inclined to keep rates low. After decades of working to tamp down inflation, even at the cost of inducing recessions, and finally succeeding, central bankers in developed economies have spent most of the past 10 years reversing course and trying to reignite it, with very little success. At a press conference on March 20, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said low inflation is “one of the major challenges of our time.”

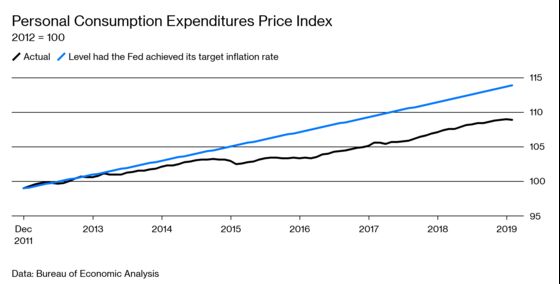

As Powell acknowledges, persistently low inflation is hard to explain using standard macroeconomic theory. Price pressures were weak in the aftermath of the global financial crisis because there was a lot of slack in the economy, including underutilized factories and workers. What’s surprising now is that even after one of the longest economic expansions in U.S. history, and with the unemployment rate hovering around half-century lows, inflation is still subdued. The Fed has repeatedly missed the target it set in January 2012 of 2 percent annual change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures. Once you strip out volatile food and energy prices, inflation by that measure has reached 2 percent just one month (July 2018) in the past seven years.

As recently as January, Powell was declaring that the economy seemed strong enough to sustain two quarter-point interest-rate increases in 2019, on top of the four the Fed orchestrated last year. But inflation has again come in below the Fed’s expectations, and both 2019 rate hikes have been erased from the median forecast of the bank’s policymakers.

While five-digit, Venezuelan-grade inflation is destructive, a little bit greases the wheels of commerce. It makes it easier for companies to give stealth pay cuts to underperformers, because keeping their pay flat is tantamount to a reduction in real wages. Some inflation is also useful to central banks because it helps them fight recessions. To spur borrowing, they like to cut their policy rates to well below the rate of inflation. But they have no room to do so if the rate is barely above zero. A surprise decline in inflation also punishes borrowers by making their debts more burdensome.

So who, or what, slayed inflation? There’s increasing evidence that the killer wasn’t the Fed or the European Central Bank or the Bank of Japan, even though the central bankers have tended to believe in Milton Friedman’s dictum that inflation is “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Researchers are finding that low inflation is in large part a consequence of globalization or automation or deunionization—or a combination of all three—which undermine workers’ power to bargain for higher wages.

In other words, the capitalists killed inflation. In the decades after World War II, Polish economist Michal Kalecki depicted inflation as a product of the struggle between business and labor. If workers manage to extract big wage increases, their employers recoup the costs by putting through price increases, forcing workers to seek even more, and so on in a wage-price spiral. In contrast, if workers have little or no leverage, as is now the case in many industries, the wage-price spiral never gets started. Kalecki’s Marxian analysis survives in Modern Monetary Theory, a once-fringe flavor of economics for which liberal Democratic politicians such as Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York have developed a taste.

Surprisingly, even the Fed has entertained the idea that inflation could be related to something like class struggle. Richard Clarida, a Columbia University economist who began a four-year term as vice chair of the Fed in September, likes to point to the decline in labor’s share of national income, to 66.4 percent at the end of 2018, from a range of 68 percent to 71 percent from 1970 to 2010. His implicit argument is that business could give labor a solid raise without raising prices of goods and services, as long as it was willing to give back some of its increase in the share of national income.

With inflation dead or dormant, central banks are taking hits from the left and the right for not doing more to juice growth. Stephen Moore, Trump’s pick (as of now) for an open seat on the Fed’s Board of Governors, has said that “hundreds” of Fed economists are clueless and should be fired. “I’ll say that again: Growth does not cause inflation,” he told Bloomberg Television on April 11. “We know that. When you have more output of goods and services, prices fall,” he said. Moore’s argument is a supply-side one: that growth increases the productive capacity of the economy at least as much as the demand side, so there’s no upward pressure on prices.

In the view of Harvard economist Lawrence Summers, persistently low inflation is a symptom of what he calls secular stagnation. Given that interest rates are already low, one essential treatment for such a condition is an aggressive fiscal policy, according to Summers, who was President Bill Clinton’s Treasury secretary and director of President Barack Obama’s National Economic Council. He’s not a fan of Trump’s tax cuts but argues that the federal government should step up public investment, even if it means taking on more debt.

Germany and other northern European countries that carry little debt are particularly well-positioned to spend more and help fire up global growth, argues Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Germany’s Allianz SE and a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. “Unfortunately,” he writes in an email, “the political will to implement such an approach is lacking.”

Which means this could drag on for a while. In an April 15 presentation at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Summers said the major industrial economies will be stuck with low inflation and low interest rates “for another 10 to 15 years, at least.”

One reason for lowflation’s persistence is that it’s connected to the aging of societies. “I used to say that was just an excuse, but I begin to wonder if the Japanese have a point,” says Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute. “Maybe aging affects people’s willingness to bargain for wages, to switch jobs, to invest.”

Part of why inflation has stayed low even as unemployment has tracked lower is that companies are finding new ways to hold the line on wages. Juan Salgado, chancellor of City Colleges of Chicago, a network of community colleges, says employers such as Accenture Plc and Aon Plc are recruiting people with an associate’s degree for jobs they once reserved for those with a bachelor’s degree. Then they invest in training to bolster the skills of new hires.

Standard macroeconomic theory holds that no matter how inventive employers get, tight labor markets must eventually lead to higher wages and general inflation. An April paper by Joseph Gagnon and Christopher Collins of the Peterson Institute argues that unemployment is finally low enough that there could be “moderate increases in inflation over the next few years.” But the authors add cautiously that there could also be little change. A January paper co-authored by Olivier Coibion of the University of Texas at Austin and Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Mauricio Ulate of the University of California at Berkeley finds “no evidence that inflation is on the brink of rising.”

One new idea gaining traction is for central banks to sacrifice a bit of their independence and coordinate their efforts more closely with fiscal authorities, who are in charge of taxation and spending. The Peterson Institute’s Posen told Bloomberg that if the federal government embarked on big projects in fields such as clean energy or health care, it could induce the private sector to follow suit. That could put the entire economy on a higher growth path, he says.

The Fed knows its credibility is in jeopardy, which is why it launched a “Fed Listens” tour that will culminate in a research conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago on June 4-5. Topics will include monetary policy strategy, tools for managing the economy, and communications practices. (Salgado is on the speaker roster.) Fed officials have already made clear that, despite the call for new ideas, they’re not ready to write the obituary on the 2 percent inflation target just yet. —With Matthew Boesler, Rich Miller, and Craig Torres

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.