China Loses a Tech Generation as the Big Payoff Promise Fades

A generation of Chinese tech workers is confronting a new reality as the industry endures its worst slump since 2008.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Terry Hu first sensed trouble at the Beijing gaming startup where he worked when his boss stopped showing up. Then the stockpile of freebies for users—gift cards, plush toys—ran out. The founder finally said funding had dried up for the company. Hu and about two-thirds of his colleagues were fired, he says. “He told us we were the best and brightest, that we might come back and work for the company someday,” Hu says, asking that the company’s name not be disclosed out of fear that it would worsen his career prospects. “It was a load of garbage.” It took him three months to land a job at an English-language center, outside the tech sector that once held so much appeal. “I’ve learned my lesson,” he says.

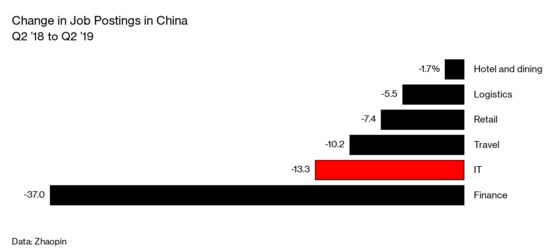

A generation of Chinese tech workers is confronting a new reality as the industry endures its worst slump since the 2008 financial crisis. China’s broader economic slowdown and the trade war with the U.S. have ended the boom that birthed heavyweights including Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and Tencent Holdings Ltd. Startups in Greater China have raised $32.5 billion via venture capital deals so far in 2019, less than a third of last year’s $111.8 billion, data from research and consulting firm Preqin shows. Job losses are mounting, and hiring has slowed: Job postings in the internet and e-commerce sector dropped about 13% in the second quarter, according to recruitment platform Zhaopin. Entrepreneurs are less willing to form ventures, so the pace of startup creation has slowed.

The tacit promise for workers in the country’s notoriously relentless tech culture—put in the hours and get rich quick—no longer holds. For years, tech workers in China have accepted a schedule dubbed 996—9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week, plus any overtime required—in return for wealth they’d watched so many before them gain. Many were willing to take meager wages, around $2,000 a month in Hu’s case. They’ve now discovered that such blind loyalty doesn’t always pay off. In March a horde of mostly anonymous Chinese programmers took to the code-sharing community GitHub to protest 996. They compiled a blacklist of companies known for not paying overtime and lodged formal complaints against their employers to local labor watchdogs. Their post went viral, garnering almost a quarter of a million followers.

Some of China’s most prominent industry figures pushed back. Alibaba’s billionaire founder Jack Ma endorsed the extreme work schedule, calling the ability to work 996 “a huge bliss” for workers in an April internal meeting with employees. Richard Liu, chief executive of Alibaba competitor JD.com Inc., said in a WeChat post that while he wouldn’t force employees to work 996, people who slack off weren’t his “brothers.”

China’s Communist Party has been grappling for months with foreign threats to the country’s tech sector. In May the U.S. banned telecom equipment giant Huawei Technologies Co. from buying American components, and other Chinese tech companies fear a similar fate. Mounting discontent among tech workers could hamper the industry’s growth, creating yet another headache for the government. “Facing a more difficult payoff, China’s 996 workers may lose enthusiasm,” says Brock Silvers, managing director for Shanghai-based investment firm Kaiyuan Capital. “This is precisely contrary to the needs of China’s developing tech sector.”

Suji Yan, the 23-year-old founder of Shanghai data privacy firm Dimension, says the younger generation values work-life balance, and he allows his 20-person team to keep flexible hours and work remotely across the globe. He thinks it could take a decade or two to fix China’s intense work culture. With their dreams of getting rich shattered, “programmers have more and more realized that they are just ordinary laborers, ones that belong to the same class as food delivery guys and are as miserable as them,” Yan says.

During the country’s last tech downturn in 2016, companies froze hiring and cut jobs, and many were told to rewrite valuations, reassess assets, and slash costs. This led risk-averse investors to pour money only into marquee companies, pushing up valuations for the country’s largest startups and ushering the rise of a few tech behemoths that took control of almost everything. This time even the hottest startups feel the pain. SoftBank Group Corp.-backed Full Truck Alliance, an app for truck deliveries, scrapped plans to raise as much as $1 billion, while artificial intelligence startup SenseTime Group Ltd. says it’s in a “nondeal roadshow” with no funding targets, months after it was said to have held talks to raise about $2 billion. Ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing internally disclosed plans to cut 15% of its workforce earlier this year—though it intends to hire in certain areas—while online emporium Alibaba was said to have temporarily halted hiring.

At the social networking company where Cherry Wang works, overcrowding used to be the norm, and there weren’t enough desks for everyone. Now rows of desks lie empty, and the product manager has watched co-workers pack their belongings on Fridays and leave, never to be seen again. About 10% of employees were eliminated at the end of last year, she says, asking that the company’s name not be disclosed so she doesn’t lose her job. Wang had been accustomed to an annual bonus of at least three months’ salary. This year? “You’re lucky not to get laid off,” she quoted her manager telling her during a recent evaluation.

Vicky Ren, 26, is grateful to no longer have to endure the long hours expected by Chinese tech companies. After graduating college in 2015, Ren became one of the country’s millions of “Beijing drifters”—people who migrate to the capital in search of opportunity. She spent two years as a marketing specialist with a Chinese internet company. After relocating abroad to help the company’s expansion in Southeast Asia, Ren grew frustrated by the endless back-and-forth with headquarters in China and the long hours—it wasn’t unusual for her to leave the office as late as 10 p.m. Underpaid and overworked, she resigned in May. She’s since found a job with a U.S. gadgets seller, where she earns 30% more and works from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. She says she’s more fulfilled and employees are encouraged to complete their tasks during regular office hours. “Everyone here,” Ren says, “thinks working overtime is embarrassing.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rebecca Penty at rpenty@bloomberg.net, Edwin Chan

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.