Brazil’s Deadly Dam Collapse Could Force the Mining Industry to Change

For years the industry has depended on these dams to contain the sometimes toxic, often dangerous, waste from mining.

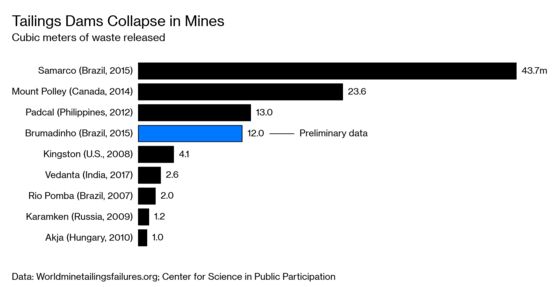

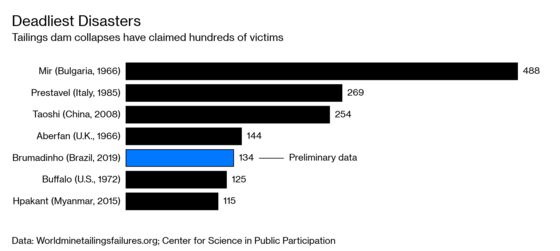

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The mining dam collapse that killed at least 169 in Brazil last month, with 141 still missing, was by no means an isolated incident. There’ve been at least 50 dam failures globally in just the last decade, according to one tally, with 10 considered major.

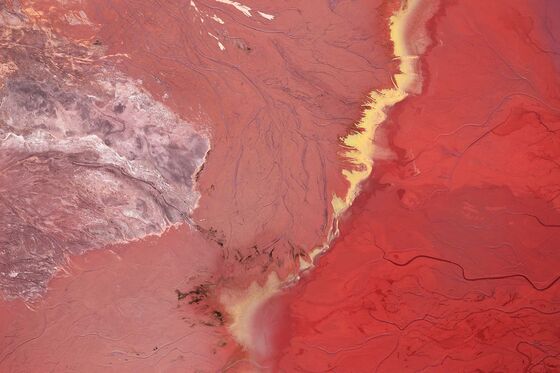

For years the industry has depended on these dams to contain the sometimes toxic, often dangerous, waste from mining. But the latest failure, which could end up as the deadliest in more than half a century, has the industry struggling to contain the consequences.

On Feb. 19, BHP Group Chief Executive Officer Andrew Mackenzie, citing the need for a “nuclear level of safety,” said his company would welcome an international and independent body to oversee the integrity of all the dams. Mining CEOs will meet in Miami next week, he said, to consider the problem. It won’t be an easy task. While many of the spills have been in the news, they range across so many countries and their causes vary so widely that they aren’t often considered as a whole. What data exist are spotty at best, collected by a jumble of mining and engineering organizations, environmental watchdogs, and academics.

David Chambers, a geophysicist who’s assembled one of the most complete lists of the failures, says at least 9 of 50 he’s tracked are “Severity Code 1,” a classification that includes disasters that killed people, freed more than 1 million cubic meters of waste, or spread tailings, the industry term for a slurry of ground rock and effluents from mining, over at least 20 kilometers (12.4 miles). Last month’s incident, involving Brazil’s Vale SA, raised the count to 10.

“We don’t know how many dams there are, we don’t know how many have failed, and we don’t know why they’ve failed,” says Chambers, founder of the Center for Science in Public Participation, a nonprofit based in Bozeman, Mont. “The basic information that we’re lacking is the real issue.”

The list of catastrophic failures will continue to grow, Chambers and others say, as long as the mining industry continues to rank cost ahead of safety in designing, operating, and maintaining tailings dams. The Brazil dam failure, for instance, involved the “upstream” method of construction, typically the cheapest by far among the techniques available and widely seen as the least stable. Under that system, part of the wall containing the pond is constructed of tailings, and it’s designed to grow as more and more waste is pumped in.

Meanwhile, climate change and aging mines have made the problem more pressing, with rainfall increasing in many parts of the world, and the need to grind through more and more rock in older properties to extract profitable ore, leaving more waste.

Mining laws vary widely from country to country, and the industry is largely self-policed. Global best practices endorsed by voluntary industry associations aren’t legally binding. Thirty large-scale mining companies scored an average grade of just 22 percent when it came to tracking, reviewing, and taking action to reduce tailings risk, according to a report released this month by the Responsible Mining Foundation (RMF), a nonprofit funded by the Dutch and Swiss governments, as well as some small philanthropic organizations.

The same report cites research predicting 14 serious failures this decade. It counts 11 as having already occurred, with two of the worst having taken place in Brazil. The biggest known spill by volume in a century occurred there in 2015. The RMF is calling for an international database of tailings dams and more independent audits, two seemingly modest requests that have proved difficult to achieve.

In the past week, Brazil has said it will ban the kind of dam used by Vale. If other countries follow suit, the impact on global mining will be enormous. The question is whether, this time, the industry will preempt government regulation with meaningful change of its own.

The International Council on Mining and Metals, a London-based industry group that will hold next week’s meeting on the failures, said in a statement dated Feb. 1 that it’s “considering a range of actions,” which it didn’t identify. Comments from individual companies largely have been sparse on details.

Rio Tinto Group, the world’s second-largest miner by market value, on Wednesday said it has 100 active tailings facilities including 21 upstream dams.The company is "again reviewing its global standard and, in particular, assessing how we can further strengthen the existing external audit of facilities," said Rio Tinto CEO Jean-Sebastien Jacques, in a statement.

“We fully support the need for greater transparency which is why today we disclosed detailed information on our tailing facilities and how they are actively managed,” Jacques said. “We will add to this over time.”

Anglo American Plc, meanwhile, says it wants to reach a point where it can operate without liquid tailings, but it’s given no timetable for that to occur. The company is developing new ways to crush ore that generate less waste, CEO Mark Cutifani said at an industry conference in Cape Town in early February.

“We’ve got to change. Whether it’s technology, better management, better design, whatever it takes, we need to lift our game as an industry,” Sandeep Biswas, CEO of Newcrest Mining Ltd., which experienced a tailings dam failure last year, said in a Feb. 14 interview.

Despite the collective call for action, the status quo may well reassert itself. That’s more or less what happened in Canada after a dam at the Mount Polley copper and gold mine failed in 2014, dumping almost 24 million cubic meters of slurry into pristine glacial lakes and rivers nearby.

An independent panel convened by provincial authorities to look into the incident noted the mining industry’s storage practices had “not fundamentally changed in the past hundred years.” Among the panel’s recommendations: Wherever possible, tailings should be stored dry, though it acknowledged retrofitting existing tailings impoundments isn’t always possible and can have risks. At Mount Polley, mining waste is still pumped into ponds.

While the two dams that failed in Brazil over the past three years were constructed using the upstream method, there are other, more expensive techniques available. One prebuilds the pond’s walls and insulates them. Experts tend to prefer it as safer, but there’s no absolute guarantee of stability. The most expensive technique, costing as much as 10 times the cheapest method, dries out the tailings and stacks them, typically underground.

Only three countries in the world ban upstream dams—Chile, Peru, and now Brazil. Chile, the world’s top copper producer, also regulates the minimum distance between dams and urban centers. But the nation still has 740 tailings deposits, only 101 of which are active, with the rest abandoned or inactive, according to data from government mining agency Sernageomin. “No one can say we’re completely safe,” says Raul Espinace, a professor at Universidad Catolica de Valparaiso in Chile.

Many mining companies would argue that banning upstream tailings dams is a step too far. Norilsk Nickel and Polyus, Russia’s two biggest miners, have 11 such dams combined. Both companies say the dams are safe, citing Russian laws that forbid active tailings storage in areas where flooding could affect villages.

In Brazil, Vale could face damages of as much as $7 billion from last month’s disaster, according to Bloomberg Intelligence, in addition to the $1.3 billion the company says it will have to spend to decommission 19 other upstream dams in the country. The question remaining: whether the consequences—both moral and financial—mark a turning point for the industry, forcing those companies that can afford to change their practices to do so while driving others out of business.

“If mining waste cannot be disposed of responsibly, we need to evaluate whether that mine should continue to be an operation or should be built in the first place,” says Payal Sampat, mining program director at industry watchdog Earthworks. “That is the question that a lot of these mining companies are afraid of. What happens if you don’t make the cut?” —With Yuliya Fedorinova, Lynn Thomasson, Elena Mazneva, and R.T. Watson

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Reg Gale at rgale5@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.