Boeing’s Charge Is Only the End of the Beginning

Putting a price tag on its 737 Max crisis doesn’t mean the aerospace giant is any nearer to putting those troubles behind it.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Boeing Co.’s willingness to put a price tag on its 737 Max crisis and set a firmer timeline for the plane’s return is a sign it sees those troubles as closer to being resolved. The risk is that the company is still the most optimistic one in the room.

Boeing late Thursday announced it would take a $4.9 billion after-tax charge in the second quarter to reflect its estimate of compensation owed to airlines that have had to scramble to adjust schedules as the Max’s grounding enters its fifth month. That estimate is based on an assumption that regulators will begin approving the Max’s return to service in the fourth quarter and that Boeing doesn’t have to make additional cuts to its production rate. This is a contrast to Boeing’s April earnings update, when it suspended full-year guidance and declined to provide a timeline for the Max’s return. It could have just reiterated that sense of uncertainty this go-around. The fact that it didn’t is likely a big reason why the stock is up in early trading.

Relative to the $36 billion in market value Boeing has lost since the second fatal crash of its best-selling airplane, the charge and the $5.6 billion it will shave off of revenue and pre-tax earnings in the quarter don’t seem all that steep. Boeing separately said the slowdown in production would result in $1.7 billion of additional costs in the second quarter. That’s on top of a $1 billion hit to margins in the first quarter. These numbers don’t include the cost of legal settlements with the victims’ families, nor the $100 million Boeing has pledged for the “education, hardship and living expenses” of impacted families and economic development of affected communities. But all in all, it feels financially manageable for Boeing. The big swing factor is whether Boeing is right that the planes will be able to fly again before the end of 2019.

Time and time again during the Max crisis, Boeing has been on the wrong side of conservatism. The two fatal crashes were linked to flight software that was added to help adapt the 737 design to accommodate new, more fuel-efficient engines, raising prickly questions about whether Boeing rushed development of the plane to better compete with the success of Airbus SE’s A320neo family. Boeing and the Federal Aviation Administration were among the last to support a grounding of the plane, playing catch-up to regulators from China, Europe and elsewhere. Boeing initially said it would have the final paperwork for a Max fix to the FAA by the end of March. Since then, Boeing has been tripped up by a string of negative headlines, including reports that warning alerts tied to the flight software system in question weren’t operational on all planes as promised. The FAA has since ordered a separate fix to a microprocessor that can get overwhelmed by data in certain situations.

Some Federal Aviation Administration officials and pilot-union leaders believe the Max is unlikely to fly again until 2020, given the time needed to make all the fixes and coordinate with international regulators, according to the Wall Street Journal. Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao reiterated on Thursday that the regulator has no timeline for returning the Max to the skies and won’t act until it’s sure the plane is safe. Ryanair Holdings Plc CEO Michael O’Leary this week said he thought it would be prudent to plan for as late as a December return of the Max. The airline is planning to take delivery of only 30 additional Max jets in time for 2020’s peak summer travel season, down from an original target of 58, forcing it to pare growth plans.

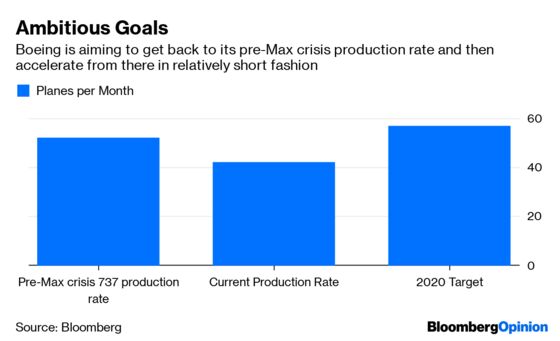

Part of the problem is that Ryanair can only take six or eight new jets per month. It’s a microcosm of the inherent difficulties in clearing out the Max inventory that’s piled up at Boeing’s factories, so much so that jets are now being stored in employee parking lots. Even with a fourth-quarter return of the Max, that makes me highly skeptical of the company’s assumption that it can not only get back to its pre-crisis production pace of 52 planes per month in 2020, but accelerate that further to 57 jets.

The odds of Boeing’s second-quarter charges being merely a starting point for the financial toll of the Max crisis are high.

I have to agree with the father of the Ethiopian Airline crash victim who called this $100 million cash pile “a PR stunt.” However well-intentioned as Boeing may be, it feels unseemly.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.