San Francisco Was Preparing for a Flood of IPO Cash That Never Came

San Francisco Was Preparing for a Flood of IPO Cash That Never Came

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It was meant to be the latest San Francisco gold rush.

After a startup boom that saw tech unicorns spend an unprecedented amount of time on the private market -- amassing lofty valuations in the process -- this was the year when dreams of IPO riches were supposed to become a reality. A city already flush with wealth prepared for a spending spree by thousands of newly minted millionaires.

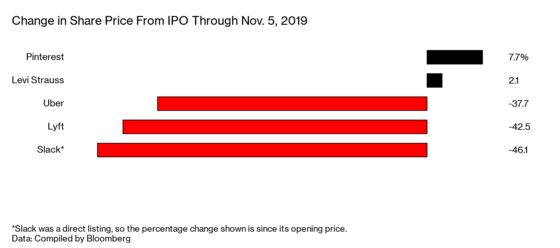

Then came the drumbeat of disappointing debuts: Lyft tumbled, Uber slid, Slack sagged and WeWork’s listing plans collapsed in an epic bust.

Now, San Francisco home sales are tepid, with prices even falling in some parts of the Bay Area. Party planners are paring back on ostentatious celebrations. Even as the short-term restrictions preventing some employees from selling their shares expire, many of them have been left with holdings worth a lot less than they expected -- or will have to wait even longer for a payout as their companies delay plans to go public.

“A lot of people joined these big startups with the hope of making a lot of money, and they thought this was going to be when it happened,” said Brandon Smith, director of estate planning at Wetherby Asset Management. “Obviously, they’re disappointed.”

In a city where vast amounts of startup wealth have been swirling for years, few people are crying for tech millionaires whose fortunes may take a slight hit. A cool-down may even be welcome for a region grappling with deepening inequality and the country’s most expensive housing.

The slowdown in the once red-hot real estate market is palpable. In the spring, the prospect of IPO-fueled demand caused some homebuyers to rush to put in bids, trying to get ahead of the anticipated surge in prices, real estate brokers say. That frenzy has faded.

“Six months ago, we were all talking about” what the IPO money would do to the market, said Mary Macpherson, an agent with Compass in San Francisco. But at a two-hour meeting in early October with top agents from other firms, the IPOs merited just two minutes of discussion, she said.

The flops have led to housing seminars such as one last month by real estate agent Robert Cruz in San Jose called “IPOs are in Trouble, Is Housing Next?” Close to a dozen people considering buying a home came to the event, including some workers in the tech industry.

“In our market, there are a lot of tech buyers reading negative headlines about IPOs,” Cruz said. It’s not just the workers at these companies who get squeezed, he said. There are ripple effects throughout the region. “Because it’s such an important part of our local economy, it really resonates with people.”

Home prices have actually been falling this year in much of Silicon Valley, where high values have put properties out of reach for many buyers. In San Francisco, the median price of a house rose just 1.8% in the third quarter from a year earlier, to $1.58 million, according to data from Compass.

Some ultra-luxury properties are finding fewer takers than anticipated. “We were expecting a little bit more of a bump,” said Joel Goodrich, who sells high-end Bay Area homes for Coldwell Banker. He currently has several listings for more than $20 million, including a $40.5 million mansion in San Francisco’s Russian Hill that comes with an art gallery and a “spa-like” guest cottage.

Demand for second homes in wine country is down too, said Tony Ford, partner at NorCal Vineyards. The nouveau riche tech executive typically shops around for glamorous mansions on a hill with three- to five-acre vineyards, he said.

“It’s still a good buyer segment, but I think that it has cooled off a little,” Ford said. “The lack of success in the tech industry, it very well sounds like it’s related.”

But while some big-ticket purchases may be scaled back, day-to-day spending for San Francisco’s tech and investing elite is little changed, said Smith, the wealth manager. He doesn’t expect his clients to make cuts to private school tuitions or big vacation budgets. The owner of an upscale electric bike store in San Francisco said he’s been “crazy busy’’ this year.

“We do have a lot of people who are in technology and they seem to be doing all right,” said Brett Thurber of the New Wheel bike store. “In this strata, it’s not that expensive to spend $10,000 on an e-bike.”

There will still be around 4,500 new millionaires from this year’s IPOs, according to Deniz Kahramaner, founder of data-driven real estate brokerage Atlasa. And some offerings have done quite well -- San Jose-based Zoom Video Communications Inc., for instance, is up 86%.

Much of the damage for tech employees’ stakes came long after the IPOs, at the end of the lockup periods in which they couldn’t sell their shares. Uber was worth almost $76 billion when it went public in May. As its lockup period expired this week, it was worth only about $46.7 billion. The IPO debacle of New York-based WeWork, meanwhile, has cast a pall on money-losing startups.

With share prices floundering and criticism of profligate spending growing, it might not look good for executives to lavishly throw money around. That’s translated into requests for event planners to tone down this year’s holiday parties.

“Clients will be like, ‘Hey will you make it look really nice, but not too expensive,’ because they don’t want to hear from employees later, ‘Why did you spend so much money?,’” said Anna Marie Rembold, president of Anna Marie Events.

The debauchery that’s a part of startup lore may also wane.

“You’ve heard of things like people renting out suites in Vegas and going crazy and tigers and whatnot -- that’s not happening right now,” said Christina Millikin, founder of Glow Events. Still, neither planner has seen a drop in budgets, which for Rembold run up to $3 million.

For some tech workers, the notion that IPO money would change their lives and lead to a spending spree may have always been more myth than reality. Srinivas Rao-Mouw, a software engineer at personal-shopping company Stitch Fix Inc., was awarded equity when he joined the San Francisco-based startup in October 2017, about a month before it went public. He estimated he’d get low-six-figures of money from the IPO that he would put toward the down payment on a home.

But his equity wasn’t worth what he expected once the lock-up period expired -- even as Stitch Fix shares at one point more than doubled. He found himself getting outbid in his house hunt this spring and then deciding to call off the search.

“The way I think about IPO money, going forward, is it’s not a panacea,” Rao-Mouw said. “It might turn out well, it might not.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pierre Paulden at ppaulden@bloomberg.net, Kara WetzelMichael Hytha

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.