Amazon Wants India to Shop Online, and It’s Battling Walmart for Supremacy

The rivals are spending billions of dollars to turn Indians into devoted customers.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Like many neighborhood stores in India, the Sri Lakshmi Venkateshwara Kirana is tiny and cramped. Single-rupee shampoo packets and bags of potato chips hang from ceiling hooks, jars full of colorful candies and sesame brittle sit on the counter. Sacks of rice and lentils are stacked waist-high, occupying nearly every square inch of the floor. It may not look like it has much to offer in the way of merchandise, but this kirana, in the southern village of Madikere, sells practically everything.

Last year the shop’s 27-year-old owner, Gangadhar N., joined thousands of other small Indian retailers in partnering with Amazon.com Inc. While cows and roosters ramble outside on the dirt lane and women walk by with bales of hay balanced on their heads, Gangadhar, who uses only a single letter as his last name as is common in India, displays Amazon’s selection to villagers on a smartphone and shows them how to find things and get the best prices. “I’m the person between Amazon and the people who shop online,” he says proudly.

Enlisting local shop owners to serve as envoys for online buying is part of Amazon’s foray into India, one of the last frontiers of e-commerce. India has a population of 1.3 billion, hundreds of millions of whom now own smartphones and are just getting their first glimpse of the cornucopia of consumption that’s accessible online. Winning here is all the more important after Amazon bombed in another immense market, China.

Reaching customers in India isn’t easy. No country is more colorfully, anachronistically chaotic. Local roads are rutted with potholes and cluttered with motorcycles, auto rickshaws, and stray dogs. Making deliveries requires Mad Max-level driving skills. Four out of five Indians earn wages in cash; credit cards are rare, and trust in transacting online has to be earned. A quarter of the population lives in poverty, and a similar proportion is illiterate. Still, the country’s middle class is growing, which is why risk-tolerant retail giants want in.

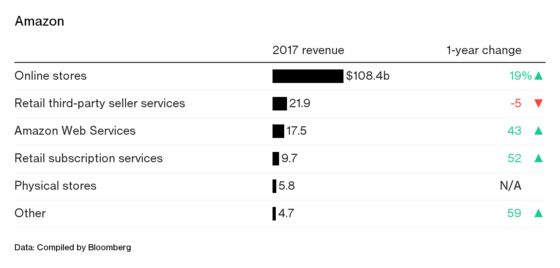

Amazon’s goal is to “transform the way India buys and sells,” according to its local mission statement. Anodyne language aside, this is a massive undertaking that, as usual with early-stage Jeff Bezos projects, is massively unprofitable. His company lost an estimated $3 billion on its international efforts last year, and analysts believe most of that was in India. Desperate to keep up, Walmart Inc. in May spent $16 billion to acquire Amazon’s primary rival in India, the homegrown online retailer Flipkart Online Services Pvt. Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. is also here, with an investment in a popular online retailer called Paytm E-commerce Pvt, as well as a stake in the country’s largest online grocer, BigBasket. All this action is almost enough to make Bezos, Amazon’s founder and the wealthiest man in the world, a household name in one of its remotest places. Almost. “I don’t know who Jeff Bezos is,” says Gangadhar, standing outside his kirana, under an awning for shade. “But if he’s made it convenient to shop from this village, he ought to be the richest.”

On the first day of each month, Gangadhar distributes leaflets around his village listing Amazon’s deals on exotic global brands such as Pampers, Gillette razors, Olay moisturizer, and Pillsbury cake mix. “Don’t be scared of online shopping, make friends with it,” the handout counsels.

When his customers order by noon, Amazon delivers packages to the store the next day via a logistics company called StoreKing. When packages arrive, as a small box addressed to a tea shop owner named Appaji did on a recent afternoon, Gangadhar leaves his wife at the store to make deliveries on foot. He grew up in the village and knows almost everyone by name.

Gangadhar’s deliveries can have the feel of a parade, with other villagers trailing him on his errands. When the procession reaches Appaji’s tea shop, where a half-dozen older men squat in darkness on floor mats sipping from small cups, the proprietor says the package is for his daughter, and Gangadhar and his entourage continue on to the Appaji home nearby.

There, in a windowless living room, where a ceiling fan whirs and a small TV blasts news and commercials in the local language, Akshatha, 17, receives the Amazon box with trembling hands and opens it. It’s a Moto G 5s, her first smartphone, which cost around $130. It’s a significant purchase for the shop owner, who sells cups of tea for 4 rupees (about 5¢) and who pays the kirana owner in cash. Later, Akshatha reports that she signed up for WhatsApp, shared selfies with friends, and became an aspiring Amazon customer. “I hear every product shown on TV is available,” she says. “For my birthday in December, I’m already thinking what to ask my parents to gift me from Amazon.”

Amazon opened its Indian website in June 2013. The group running the site, a team of Indian-born engineers who had worked at Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle and were persuaded to return home, stored and shipped products from a single, relatively small 140,000-square-foot warehouse in a crowded suburb outside Mumbai. Bezos told the team to “think like cowboys, who are wild and fast and a little bit rude, and not like computer scientists,” according to Amit Agarwal, head of the India operation. That translates as “it was OK to make mistakes. It’s important that you control your destiny and move fast,” says Agarwal, a former Bezos “technical adviser,” Amazon lingo for an executive shadow. Agarwal speaks in the narrow lexicon of the company’s public pronouncements, extolling the holy trinity of price, selection, and convenience. He’s such an avowed Amazonian, in fact, that when the India division opened, he shipped his door desk—a cherished symbol of frugality at Amazon—halfway across the world to his new office.

About a year after the launch, Bezos visited for a grandiose public unveiling of Amazon’s investment plan. He insisted on presenting an oversize $2 billion check to Agarwal while riding an elephant—a mystical symbol in India that represents wisdom and strength. But all the elephants were occupied in a regional religious festival at the time, and colleagues had to persuade him to conduct the exchange atop a heavily decorated truck. “I think God takes priority over Jeff,” Agarwal says.

Amazon now has more than 50 fulfillment centers in India. The main office, in Bengaluru (formerly Bangalore), is in a modern office tower ringed by security checkpoints. In the lobby there’s little to mark the presence of Amazon, save a small blue sign and three Fire tablets sitting on a reception desk. Upstairs, inspirational if unsettling Bezos quotations line the walls: “Day 2 is stasis followed by irrelevance, followed by excruciating, painful decline, followed by death.”

Amazon followed a familiar playbook in India. Prime was introduced in 2016, offering two-day shipping everywhere in the country. Membership costs 999 rupees, or around $14 a year, and members can watch free shows such as the standup comedy competition series Comicstaan. As it has in other countries, the company introduced Pantry, with a selection of snack foods, beverages, and household items, and, in a handful of cities, Prime Now, offering fresh food and produce within two hours.

But everything was harder in India. Amazon realized early on it couldn’t depend solely on such logistics partners as the India Post, the federal mail carrier. So it created its own network of couriers in vans, motorcycles, bikes, and even boats to reach the remotest parts of the country, such as the river islands in eastern Assam. Like its rival Flipkart, Amazon accepts cash on delivery, since few shoppers have access to credit cards. Customers have the option to deposit change from a cash transaction as credit in their Amazon accounts, one of the company’s many efforts to get people more comfortable with the idea of digital payments.

One of Amazon’s biggest challenges has been simply getting Indian merchants comfortable with selling online. Foreign retailers that sell multiple brands are prohibited by law from selling anything other than food directly to consumers, which means everything on the Amazon.in marketplace is listed by an independent seller. One way Amazon has gotten around this is to invest in joint ventures with local businesses; another is to send employees into local markets with ample supplies of chai to introduce merchants to such concepts as email, apps, and e-commerce and persuade them to list their products on Amazon. The company basically had to help teach all of India how to buy and sell online. That meant advertising loudly on television and billboards. (“Aur Dikhao,” or “show me more,” was the slogan of a TV campaign.) It also meant finding and enlisting intermediaries instead of doing away with them, Amazon’s customary approach in other parts of the world.

In one initiative, Amazon turned 14,000 local shipping offices into e-commerce training centers, called Easy Stores, where counselors are available to escort buyers through the virtual mall. Orders are delivered to the stores a day or two later, and buyers can pay cash when they pick them up.

At an air-conditioned Easy Store in the Worli neighborhood of Mumbai, customers leave their shoes at the door and line up to shop with the help of one of four agents sitting behind counters. “A sari for my mother, a lehenga skirt for my sister, sheets and blankets for the house,” says Hachnul Haque, a 28-year-old migrant from northeast India, who works in a restaurant kitchen for 25,000 rupees a month and is buying gifts for his annual journey home. Today he’s looking for a bangle for his aunt. The agent browses Amazon.in on a PC, which is also mirrored on a screen in front of Haque, as Haque takes photos of products with his phone and texts them over WhatsApp to his aunt so she can pick the one she likes best. “I’ve known the people here over a year and trust them,” he says, propping a leg up on a free chair. “There’s no tension in shopping this way.”

A 45-minute drive from Amazon’s inconspicuous offices through the gnarly Bengaluru traffic are the headquarters of Flipkart, a trio of low-slung towers in an office park that’s also home to the local branches of Xiaomi Corp. and WeWork Cos. Even on a recent national holiday, it’s a hotbed of activity, with employees preparing for “Big Billion Days,” an invented celebration like Alibaba’s Singles Day and Amazon’s Prime Day. Big Billion Days kicks off Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. “Congratulations Flipkart, we have set a new world record,” reads a giant sign in the lobby. It commemorates the company’s recent accomplishment of stacking 45 mattresses to demonstrate the durability of a Flipkart-branded bed frame.

Ask an executive at either Amazon or Flipkart which one’s ahead, and you’ll receive an indignant cavalcade of conflicting market share data. Both profess not to care about the competition while insisting that they’re winning. What’s safe to say, though, is that Flipkart was first to bring modern e-commerce to India and is still slightly bigger, and that Bezos recognized that fact and at one point was determined to buy it.

Flipkart was founded by two former Amazonians. When Amazon first opened an engineering center in Bengaluru in 2006, in a small office over a car dealership, one of the first employees was Sachin Bansal, a graduate of Delhi’s prestigious Indian Institute of Technology. A year later, Bansal brought his high school friend Binny Bansal (no relation) into Amazon, and a few months later they quit to try to replicate Bezos’ original magic of selling books in their native country.

Even before they were competing against their former employer, the two had trouble escaping its shadow. “You are just copycats! How is this anything different from Amazon?” Amar Nagaram recalls saying to Sachin Bansal in 2011—during Nagaram’s job interview at Flipkart. Amazingly, Nagaram got the job and is now a vice president there.

Early on, Flipkart accepted cash payments from customers and began training Indian merchants in the particulars of e-commerce. To help deliver packages in Mumbai, it enlisted the dabbawallas, couriers who make up a century-old network that brings hot lunches in intricately color-coded boxes from workers’ homes to their offices. Meanwhile, the company raised billions from investors such as Tiger Global Management, the South African investment fund Naspers, and the Silicon Valley venture capital firm Accel. By the end of 2015, Flipkart was worth $15.5 billion and one of the most valuable startups in the world.

In 2016, trouble hit. As Bezos continued to write large checks to Amazon India, Flipkart sales slowed, and the company had to lay off workers. It accepted a lower valuation of $11.6 billion when it raised an additional $1.4 billion in April 2017 from a consortium that included Tencent, EBay, and Microsoft. And because Flipkart was now majority-owned by foreign funds, it could no longer sell products directly and had to adopt the marketplace model, where independent merchants list their products and make the sales. Like Amazon, Flipkart invested in affiliates to carry the most popular inventory. But the shift, executives say, sowed internal chaos and hurt the experience for both buyers and sellers.

By the end of 2017, business was improving. Flipkart’s acquisition of Myntra, a successful fashion website that carries global brands and ethnic Indian clothes, created another popular category on the site alongside smartphones. Sachin and Binny Bansal had also recruited back their former chief financial officer, an intense, fast-talking Tiger Global alum named Kalyan Krishnamurthy, who’d worked at EBay Corp. in Asia a decade before and learned from its fatal lack of interest in tailoring its service to specific regions in India. “This is a place where you cannot have one strategy,” says Krishnamurthy, who became Flipkart’s CEO. “You need to have 24 strategies and maybe even more.”

Then the suitors came calling. For the first six months of 2018, the Indian media intensely charted rumored talks between Flipkart and Walmart. What was unknown at the time is that Flipkart executives had also started talking to Bezos, according to two people familiar with the negotiations, and even visited the Amazon CEO at his Seattle home.

With Peter Krawiec, his top M&A deputy, Bezos started working on a deal to acquire Flipkart. Members of Walmart’s management team got wind of it when they happened to be in India taking a private Harvard Business School executive education course about the country.

Intoxicated with the potential of the Indian e-commerce market, the two retail titans battled for the deal through last winter and spring, bidding up Flipkart’s valuation from $11.6 billion to $20 billion. Amazon eventually offered the higher bid, says someone who was privy to the negotiations, and at least one major Flipkart backer, SoftBank Group Corp.’s Masayoshi Son, favored it. But while Bezos was confident he could get the deal approved by Indian regulators, some of Flipkart’s investors feared the uncertainty of the antitrust approval process. Eager to cash out of a decade-old startup, Flipkart’s board agreed to sell to Walmart. Walmart CEO Doug McMillon visited India after the acquisition was announced and told Flipkart employees, “It is our intention to just empower you and let you run. Speed matters. Decisiveness matters.”

Amazon.in’s and Flipkart’s customers are generally wealthy, speak English, and live in the most cosmopolitan Indian cities. Getting them to sign up and start buying was hard—but not that hard. The real challenge for the two companies and for the future of e-commerce in India, executives at both companies say, hinges on the next 100 million users—a portion of the population that is less educated and speaks 1 of the country’s 22 major languages at home.

This fall, Amazon introduced a website and mobile app in Hindi. It’s not just a clumsy machine translation, executives contend. Images are prominently displayed, and such words as “free” and “mobile phone” are so commonly used in everyday conversation that they’re left in English. “This was not a gimmick,” says Agarwal. “This is an intent translation that keeps in English what should be in English and translates into Hindi based on what our customers really talk about.”

Over at Flipkart, employees also stress the urgency of finding the next group of users. “We are rebooting ourselves here, and one of our biggest changes in mindset is that we no longer resemble our customers,” says Nagaram, the head of user growth. Flipkart has sent researchers into towns and villages to study what people want and how they use their smartphones, while preparing versions of its service in five local languages. It also recently introduced 2Gud, a mobile website targeting lower-income buyers that offers a selection of used and refurbished consumer electronics and appliances.

Another major front in the battle for customers is groceries, which make up about half of the Indian retail pie—and is a highly fragmented market even by local standards. Both companies are experimenting. In addition to delivering groceries in a few major cities, Amazon was recently part of a group that acquired More, the fourth-largest grocery chain in the country, which has around 600 supermarkets. Flipkart has started a grocery delivery service in Bengaluru. It also thinks it can learn a few things from Walmart—the biggest grocer in the world.

Looming over all this is the possibility that politics, not business tactics, could decide the battle for India. The government reviews its e-commerce guidelines every few years, including the rules that prevent foreign-owned companies from holding and selling products to consumers. A draft of the new rules, leaked over the summer, suggested that the guidelines could get even tougher over the next year or so. They would limit Amazon, Flipkart, or their affiliates from holding any inventory at all. The new rules would probably yield an advantage to truly indigenous companies such as Reliance Industries, a conglomerate that’s also one of India’s largest store owners. Owned by India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, Reliance declared this summer that it will create a hybrid online-and-offline retail platform.

Agarwal promises compliance with all local laws and says all the company can do is make the government see the advantages of letting the company sell goods directly. “It’s kind of wasting my time trying to think of things that I don’t control,” he says. But of course Amazon is lobbying hard in Delhi. It spent $107 million on legal fees in India last year, according to public filings.

At noon on a Saturday, SP Road, Bengaluru’s wholesale electronics market, feels desolate. In the tiny, mostly empty stores that pack the street, shop attendants arrange and rearrange their goods. As sales of smartphones and computers have skyrocketed on Amazon and Flipkart, they’ve cratered here.

Caught in the downdraft is Jagdish Raj Purohit, the owner of a store that bills itself as Sunrise Telecom. It’s a shoebox of a space, and Purohit is seated behind the cash register at the entrance. Along one side are hundreds of cases for every conceivable smartphone model. On the other is a combination of low-end and midprice phones, as well as a Vivo V11, an upscale model from China that sells for 26,000 rupees. Purohit doesn’t expect to sell many. “All mobile sales have gone online,” he grouses, when asked the customary Hindi question “Dhanda kaisa hai?” (“How’s business?”) “Flipkart and Amazon are always advertising discounts on such phones, so who will come here?” He tries to make up the shortfall by selling accessories.

At Raj Shree Computech down the street, Mahendra Kumar and his two brothers have been selling computers and accessories for a dozen years. For the last few, business has been “thoda thanda,” a bit cold. It’s not a great mystery why. “Whoever comes here quotes laptop prices from Flipkart and Amazon straightaway, even before we say anything,” says Kumar. Or “they’ll come here and try many headphones for sound and then walk out saying they’ll be back later. We know they aren’t coming back.” Like his fellow shop owner down the street, Kumar is reluctant to become a seller on Amazon or Flipkart because margins are slim and returns create headaches.

While e-commerce is churning up SP Road, its impact is less obvious at K.R. Market, a cacophonous outdoor bazaar about a 10-minute rickshaw ride away. Sari-clad women hawk mounds of eggplant and beetroot, workers carry gunny sacks of sweet lime, orange, and jasmine from trucks, vendors scream out prices, and buyers haggle as they fill bags with produce. Here is Indian retail in all its chaotic originality, untouched, for now, by the internet and the industrialists looking to build their empires on top of it. Ramesh Kumar, who for 30 years has sold mountains of blood-red pomegranates, has never even heard of Amazon. “Where is Amazon market?” he asks, furrowing his brow. “Are they opening near here?”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net, Jim Aley

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.